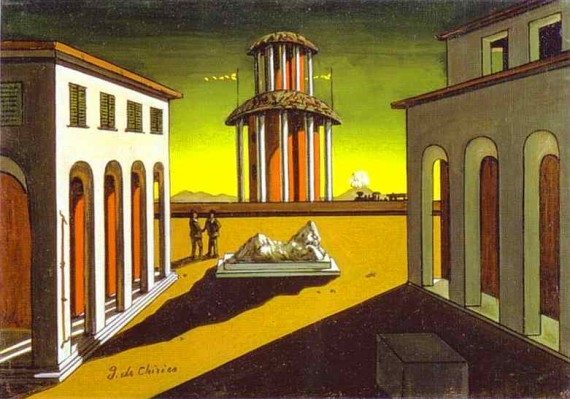

One of the site-specific pieces in Prospect.2 didn’t make it in time for opening weekend. Francesco Vezzoli‘s statue “Portrait of Sophia Loren as the Muse of Antiquity (after Giorgio de Chirico)” was held up by U.S. Customs, but it is now in its place in Piazza d’Italia, and it’s the sort of installation that makes Prospect.2 important. The “de Chirico” referenced in the piece’s title is the painter who in 1913 painted a piece titled “Piazza d’Italia,” which inspired American architect Charles Moore to create Piazza d’Italia in New Orleans in 1978. In Vezzoli’s sculpture, a gilt bronze Sophia Loren is holding a take on de Chirico’s Piazza d’Italia to her chest while standing in Moore’s version of it.

By itself, it’s a smart, slightly complicated network of references, made more engaging by the way no recreation of de Chirico’s painting is unduly faithful. Vezzoli’s Sophia is holding de Chirico’s square arches near the middle of Moore’s Roman disco, just a few feet from an obelisk with the names of prominent local Italian-Americans (and others) involved in the making of Piazza d’Italia. Presenting the famous Italian actress as the bearer of art history recognizes that American culture is so obsessed with celebrities that there’s a television network dedicated to them, and it’s hard not to see the piece as a swipe at celebrities themselves. Would anybody besides me pay to see a Kardashian family spelling bee as they wrestle with the name “de Chirico”? Hear their ideas of who de Chirico might be?

For me, the success of Prospect.1 was way pieces of art drew attention to the the spaces they inhabited. Nothing says how decimated the Lower Ninth Ward was like the fact that there was room to build an ark there. In this case, Vezzoli’s sculpture gives people a reason to visit Piazza d’Italia, which is a beautiful, slightly surreal space in the middle of the CBD to start with.

At first, I thought Sophia was situated too close to the center obelisk, which crowded her, but she’s at the point where a network of fountains that start at the very back of the piazza end, drawing attention to the way the water moves from the back to the front of Moore’s creation. And I’d never noticed how phallic this water-bearing structure was until Sophia was standing at the end of it. The way she shined in the morning light drew my attention to the other shiny ornamentation in Piazza d’Italia that I had never noticed before. Those touches are very much of Piazza d’Italia’s late-1970s moment – faux-futurist elements that would eventually find cheesy expression in movies such as 1980’s Flash Gordon.

Vezzoli’s Sophia doesn’t have the same presence as the real Loren, though the face is unmistakable and regal. Her body’s slighter, more bookish. She’s almost clutching de Chirico’s arches to her chest like her journal, and that desexualizing transformation – along with the bronze itself – keeps Vezzoli’s piece from being an elaborate wisecrack or dismissably pop. In a city with such a rich Italian heritage, the piece has additionalvibrancy, and it’s one of the must-sees of Prospect.2.