An important conference is coming to New Orleans on June 3-5: the National Independent Venue Association (NIVA) will be held in New Orleans for the first time from June 3 – 5.

NIVA is a relatively new organization, formed in response to the devastation in live music that occurred beginning with pandemic in March 2020.

Of course, musicians’ ability to play and to make a living was affected just as badly: no venues means no live music.

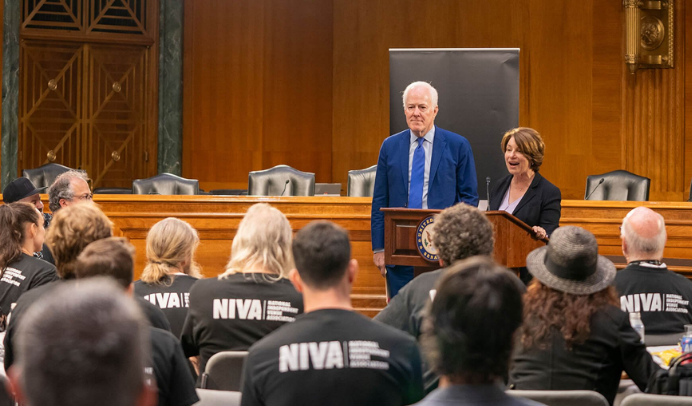

NIVA took the bull by the horns and successfully lobbied Congress to provide relief to venues by advocating for (and getting passed) the SVOG (Shuttered Venue Operators Grant) that provided $16 billion in grants to closed venues. Grants are administered by the SBA’s Office of Disaster Assistance. SVOG provided emergency assistance for eligible performing arts businesses and was set up to support the ongoing operations of eligible live venues and operators, live venue promoters, theatrical producers, talent representatives, live performing arts organization operators, museums, and motion picture theaters during the uncertain economic conditions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is getting more and more difficult to operate a venue with music. NIVA is a national organization that aims to change that.

OffBeat’s Publisher Jan Ramsey spoke with Stephen Parker, the Executive Director of NIVA to talk more about why it’s important for venue/bar/festival owners and operators to work together: financial and economic clout, and a lobbying group for live music throughout the country.

Get more info about registering for NIVA here, and view the program for the three-day event here. Opening party is on June 2 is at Tipitina’s at 7 p.m.

JR: Stephen, nice to meet you. I’m glad NIVA’s [National Independent Venues Association] conference is going to be in New Orleans because it’s an organization that’s been needed for a long time. Can you tell me a little bit about yourself? How long have you worked for the organization?

SP: I started January 2023, about a year-and-a-half ago. My background is in politics and policy, so I’m based in Washington DC. I’ve worked at the state level for both Democratic and Republican governors. Then I went to an organization called the National Governors’ Association and was there for 10 years. I was the federal lobbyist for governors in DC, and then came over to NIVA with an intermediary stop in venture capital along the way. NIVA has been wonderful. This is a wonderful organization around for the right reasons, and a young organization that still has so much room to grow.

JR: Yeah. I agree. Totally. Did you ever have any experience in running a venue or doing a venue?

SP: My experience in the music industry is primarily through music education. We did a lot of music education work at the National Governors’ Association, or at least I did it. I have worked with the CMA Foundation, which is a grant-making organization out of the Country Music Association for music education. Then during the pandemic I worked quite a bit with the Country Music Association and other music industry partners on pandemic-related unemployment.

JR: Well, that was a big deal for us, for sure.

SP: Yes, and other music-related topics that Congress was dealing with during the pandemic. Due to my affiliation with the Country Music Association, I certainly have experience in music associations, but I have not—beyond music associations—worked directly in the industry. But I also think that gives an interesting perspective, I have 1,400 members with thousands of employees that know the music industry. My job is to guide them through the advocacy process and to have a well-run association, and I certainly have experience in doing that.

JR: Yes, definitely.. How old is NIVA as an organization?

SP: Four years old.

JR: Well, that’s pretty amazing that you have 1,400 members in only four years, and you managed to get to the SVOG (Shuttered Venues Operators Grant) that you guys got through the federal government during the pandemic to help venues. That was great for our local people for sure.

SP: It was the largest arts grant in US history. The state of Louisiana and the City of New Orleans benefited greatly from that program.

JR: Yes, indeed. I know some venue owners that unfortunately didn’t get to take advantage of the situation for whatever reason. The ones that did were extremely grateful for the help. Have you worked with people throughout the rest of the country like Howie Kaplan, who’s head of the city’s Nighttime Economy Office?

SP: Indeed. We’re fortunate that we get to work with an organization called Nite-Cap.

JR: What is that?

SP: It’s an organization focused on the nighttime economy. It’s across the country as a resource for “night mayors” as they’re often referred to. They’re an organization that essentially is a convening body just to make sure that all the nighttime economy managers from across the country from cities are able to come together. We’ve been fortunate to work with roles similar to Howie’s and Austin and Sacramento and Los Angeles and San Francisco, Philadelphia, DC, New York and even in places like Iowa City, Iowa.

JR: It took New Orleans years to get it established since I started pushing the idea in 2017. . I’ve been pushing this idea ever since I heard about it from Jim Peters, the RHI – Sociable City Network.

SP: Love Jim. He’s so great.

JR: He’s been doing this for a long time. I started talking to him about it years ago, thinking, well, gee, we really need this. But despite New Orleans’ reputation as being a music city and all this stuff, it still is not calibrated, I guess, to deal with the inherent problems and opportunities for venues and musicians, and for the city. I think that one of the problems that we have in New Orleans is that what I’ve called the music ecosystem…it includes venues, musicians, festivals, production, booking and more. You can’t have musicians and you can’t have music without venues. Musicians and bands don’t all play on the street. It’s a situation where they all need each other. It’s an ecosystem. You have to have venues. What do you think is the hardest stereotype that you’ve had to deal with when you are doing your job with government people? What is the most difficult stereotype to break through in terms of business?

SP: It’s that we’re [live music] is doing as well as some of the large multinational conglomerates. But we are small businesses. The story of independent venues and promoters is the story of small business in America.

JR: Absolutely. Well, musicians too, for that matter. Musicians are all entrepreneurs.

SP: Exactly. The issues that are face all of our venues are significant. They’re facing competition issues. They’re grappling with inflation. They’re trying to help artists and teams that are also dealing with inflation. Sound ordinances are restrictive in some cases and some are impossible to deal with in their jurisdictions. Property taxes continue to go up, and in many cases are not fair to independent venues. Local amusement taxes are being added to their tickets even though venues aren’t benefiting from them. It’s for the larger venues and sometimes sports stadiums. Insurance costs are going up. Insurance coverage is going down. Alcohol permitting is a challenge. Parking is a challenge.

Mass transit is a challenge. Rapidly shifting cannabis policies are a challenge. Local development projects are squeezing out venues and promoters from having a space. Drug overdoses are happening and venues, and venue owners are trying to grapple with getting the training their staff needs and the medication that their staff needs to treat those outside and inside their venues that are suffering with these afflictions. Then there’s a complicated patchwork of US performing rights that are causing venues to pay a lot of money and the artists that are on their stages aren’t benefiting. There are lots of issues that our venues are dealing with, but at the heart of it is that many of these folks are not doing this to make money. They are doing this because they want to bring some of their favorite artists or the up-and-coming artists that they’ve heard about to their venues and watch the fans enjoy it.

JR: I guess New Orleans may be similar to a town like Memphis or even Nashville. We have area entertainment districts that that attract tourists [Bourbon and Frenchmen]. We have Bourbon Street, which has changed drastically over the past 50 years. Then we have Frenchmen Street, which is another tourist street, and I think we are grappling with that too. The backbone of our economy is tourism. When there are no tourists in town, even the venues that are not in the tourist streets, like Bourbon and Frenchmen, still are suffering because they just don’t have the ability to market the way they used to or hire the way they used to.

The booking in a place on Frenchmen Street or Bourbon Street, for example, is vastly different from a place like Tipitina’s, which is far off the beaten track. They all have some things in common, but in New Orleans, you really do have to pay attention to tourists. It’s funny because a lot of local people think tourists are a scourge, but they’re the ones that keep everything blowing and going.

SP: I’ve learned a lot about New Orleans venue situation from Howie [Kaplan]; we’ve done some site visits, and it seems like the venues and promoters had a hard summer last year.

JR: Way beyond hard. I wrote a column in August 2023 sounding an alarm for live music in New Orleans because I heard from so venues what a bad summer they had. We don’t have tourists here in the summer. They come, but they trickle in. It’s not like October or Jazz Fest or other times in the year when the city has a lot of visitors.

SP: Essence doesn’t bring tourists?

JR: Essence does, but it’s one weekend and we need the people it brings in in mid-summer. The thing about Essence is that it has a lot of programming, but tends to be very self-contained. Unless there’s a private party, like on Bourbon Street or something, the people tend to stay at or near the Superdome or the Convention Center. The hotels make out and the restaurants make out, but the venues, not necessarily. That’s a problem. The city of New Orleans gives Essence a monetary incentive to come here. This has been going on for years where they’re trying to get the Essence people to understand that you’re coming here, and we want you to stay here for a while, enjoy yourselves, but you also need to get your attendees outside this one little sphere to enjoy what’s outside the Convention Center and Superdome.

SP: I will say what I’ve heard is that summers are hard. What we’re seeing is that venues that would normally be open seven nights a week or six nights a week may have had to reduce the number of days that they are open. They may be hesitant to open, even if they know that a conference is going to be in town because if they open and they have a band, they may take a loss. It’s becoming harder and harder for them to have certainty in what they are ultimately able to do.

JR: What happens here is that we have Jazz Fest, and everyone, the whole ecosystem, capitalizes on Jazz Fest for those two weeks. After that, everybody just buckles in for the summer because they know the summers suck. They have always sucked because, like I said, there are just fewer visitors that come here. Or if they do come here, they’re not like a convention of doctors, who have a lot more money to spend. They’re not like the people that come in and spend a lot of money like you ordinarily get. Every summer is bad, but last summer it was brutal. It was bad.

Like I said, I hear it every summer, “It’s really bad,” but last year a guy who sold his venue on Frenchmen Street who’d been trying to sell it since before the pandemic, he was still on the market last year. He said, “I don’t know if I can continue to do this anymore.” Because what he did is he charges a cover to get in on Frenchmen, and there’s a whole thing around here locally on Bourbon and Frenchmen Street about the venues not paying the musicians, because they don’t charge a cover, and the bands have no guarantee. He said, “I want to pay a guarantee to these musicians. I’ve been doing this for years. He said then, “But I can’t even sell enough drinks to cover the cost of a band.” He says, “I’m having to pay them out of my pocket.”

He said, “The only other thing that I think I could go into would be to do what most of the venues on Frenchmen Street do, they let people in free.” It’s the Bourbon Street model. You go in, you don’t pay a cover. You drink and you listen to the music, and the bands work for a percentage of the bar, if that. This owner said, “I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to have that model,” because he was in it to showcase musicians, but not everybody here has that mindset. He ended up selling it to a group of operators that own Frenchmen venues, and has moved on to promoting shows. But just last week, the Palm Court Jazz Café,a venue that’s been around for 30+ years, is closing.

It’s on Decatur Street, close to Esplanade and has been around for at least 30 years. I got an email that said they were closing because they just can’t keep up with the cost of doing business anymore. Everybody really took notice of it closing because it could happen to a lot more people. There’s also a restaurant that’s closing down on Decatur Street. It’s a function of the economy because things are so expensive now and they’re getting worse, but there’s little perception on the part of the City that these people need help, and how to help.

People from all over the world recognize New Orleans’ music as a draw, but they don’t understand the nuts and bolts of what running a club and employing musicians and all that stuff, they don’t understand that. The city does not have any connection. When Howie became the head of the nighttime economy, I thought, well, this is going to be good because he knows what it’s like to have a venue. He understands it, he’s run a venue for a long time

What are some of your initiatives that you have, your goals that you have, say in the next year for NIVA? For what you plan to do for your members?

SP: Before I get into that, let me just respond to what you just said. Part of the issue with the fact that live entertainment has never had a national organization to fight for its interest is that we have a lot to do in a little time. As only a four-year-old organization, we spent the first two years of our existence fighting to pass Save Our Stages.

The second year of our existence was spent implementing the programs and making sure that people actually got the money that we fought to get from Congress. We spent the third year of our organization trying to make sure that we could have a sustainable membership and have a model that would allow us to have staff and continue to exist. We spent the fourth year of our organization fighting for ticketing reform at the federal level. Throughout all of that, we’ve been trying to collect the best data possible to tell our story. Airlines and airplanes started in 1903, and within 10 years they had an advocacy organization in Washington DC. Live performance has existed on this continent since before our nation was founded, but it’s only been in the last four years that we’ve had an advocacy organization nationally. We have to better tell our story, and what we’re hearing is that venues and promoters are struggling.

What we know is that venues and promoters are struggling. What we have to figure out is how widespread it is, and what have to do to figure out what the core issues are that are causing this struggle so that we can help them. Our main priority this coming year—and I think that this is fitting given that we’re coming to New Orleans, a city that is starting to focus on the nighttime economy—is what can we do to gather the best data and research possible to know where venues are at in terms of their financials. But also we need to know what impact venues have on communities across the country, financially and other intangibles, so that we can tell our story and advocate to the broader industry for why they need to prioritize working with our venues and our promoters. Also, to advocate to governments for why they need to take us more seriously, and to ensure that at the same that they’re valuing all of these other pieces of their economy in terms of giving them a seat at the table in terms of investment because they think that they’re critical to their economy.

We need to show how critical to every single state, local and national economy we are. From our perspective, that’s going to be our top priority moving forward. I think it’s fitting that that priority that we’ll be talking about starts in New Orleans, given the work that Howie Kaplan has done working for the mayor. But also, we’re not resting on our laurels. We’re not just looking at the future. We’re also looking at the things we’ve done over the last year. One of those things is we started a NIVA Savings program. It is a group discount program. We are using the collective power of our industry, and we’re trying to build out a program that’s ultimately going to help venues. We have started with what we viewed as the easiest things to start with, which is food, trying to make sure that those venues that serve food can get the most significant discounts possible on food from two national suppliers. We have started that program in January, and we’ve seen venues saving between 15 and 25 percent on food every month or on every invoice.

JR: Where is that active right now? How many cities?

SP: It’s active across the country. It is a new program. It’s only about three months old, so it is still a growing program. We are in the dozens. We are not in the hundreds yet of venues and promoters that are using it. But that said, those who are using it are seeing savings, and we ultimately need to grow the program so that it works for everybody. Our hope is that we can look at things that are a benefit to everyone, not just venues. Promoters have hard costs. Venues have hard costs. We’ve seen group discount programs that have offered discounted insurance. We’ve seen group discount programs that have offered discounted cups and supplies. We are starting to do that, but we need to grow it. So really, we have ambition to make sure that we’re growing the categories of things and goods and services that we can offer to our members to make life easier for them. Because ultimately, if they are investing in us, we need to invest back in them.

So that in addition to the advocacy that we do, in addition to the community that we build through our conference and through virtual convenings throughout the year, we also want to make sure that they’re getting a clear dollar-for-dollar return investment for the dues that pay under our organization. NIVA Savings has been a way for us to do that. Over the last three months, we’ve been working to grow that program and educate members on what the potential for that program is so that they can figure out if it’s right for them.

JR: How do you recruit members? Word of mouth?

SP: Mostly. But also, it’s me trying when I go to communities to try to make sure that we’re delivering the right message to show why it’s worthwhile to join NIVA. There’s never been an organized community of independent stages before, and that’s what NIVA provides. But also, we advocate at the state, local, and federal level to make sure that venues and promoters that are independent have a seat at the table, which they’ve never had before. We are trying to build out our services and offerings for our members to go just beyond advocacy and community to get into making sure that we’re driving fans to independent venues and promoters and stages. Also, making sure that we are creating savings opportunities for them so that their life can be just a little bit easier at the end of the month when they get those bills.

JR: One of the things that I know that always works in terms of exposure and interest is to provide people with good data, and you mentioned that. There is no good data in New Orleans at all. There is none. I have tried for 35 years to try to organize some of the venues, and a lot of them don’t want to work with anybody else. But by getting that info, you can provide data that shows people that these venues have a real economic impact. How are you planning on gathering the data that you need to compel people to join NIVA?

SP: I think there’s two categories of information. One is what is the economic situation of venues? How are venues doing? Are they profitable? Are they just making it? Are they taking a loss? Those are sensitive topics to discuss with venues. It’s also sensitive data to collect because venues want to do well, and so we’ve got to figure out how we can bridge that divide in terms of what we’re able to communicate publicly about the state of US stages, but also what venues are willing to share. That’s the first and hardest part.

The second piece I think is a little bit easier in terms of data collection. It just will take some work on the backend to make the appropriate evidence-based calculations that we need to, which is how are venues and promoters and stages that are independent across the country contribute to their communities and to the state, local and national economy? There are economic impact studies that have been done across the country on the arts sector, particularly the nonprofit arts sector. One example of a wonderful study from one of our partners is the Arts & Economic Prosperity project that’s conducted by Americans for the Arts. What a wonderful model of what a national study can look like.

JR: I used to work for a consulting firm, and one of the things that we did obviously is we looked at data to try to help our clients. We looked to see what population was growing, and what was the market—is it changing? I worked for a CPA firm that specialized in the hospitality industry. They used to do a newsletter, and I think they did it on a quarterly basis. It was based on a sample of hotels by size and by location in the city, so what they would do is they would have participating hotels and those operators would provide information. It was a CPA firm, so I guess they felt safe providing them with information. What they would do is to gather information by size and by location, they would aggregate it (the info was never identified by individual hotel), and then they would send it out to all the hotels who had a subscription.

A hotel could see how they were doing compared to other hotels, based on size and location. If their revenue per room was $25 and everybody else’s is higher (or lower), they could see how they were doing compared to a valid sample. I thought, well, that might work for venues. What you find in New Orleans, what I find anyway, is that people don’t understand that in order to make intelligent decisions you have to be able to compare information over time. I guess you don’t have the benefit of that because the NIVA is only four years old.

SP:

Well, I think we do have some benefit, one, comparing data over time. I think we’ve got access to SVOG data, the Shuttered Venue Operators Grant data, which is limited. But from that, that’s a nice window into time before the pandemic, particularly looking at. I’ll just say long story short, data and research is a huge priority for NIVA in the next fiscal year, which for us runs from July to June. In fiscal year 2025, as we look at after the conference ends, what we’re going to be focusing on the next year has to be research so that we can better tell our story.

It needs to be the story of where venues are at financially and how well they’re doing and some may not be doing well. But also, it needs to be the story of what our impact is on communities overall regardless of how well that you’re doing financially. If a stage is operating in a community, what does that do for restaurants around them? What does that do for state and local tax revenue? What does that do for visitors? And a whole list of other things and benefits that we believe in independent stages, venues, promoters, performing arts centers, festivals can provide across the country.

JR: Have you had any pushback on getting information from the venues?

SP: We are, yeah. We’ll start our [data] collection at the conference, so we’ll see. We need to build trust. Everything is trust. Everything is trust. We are eager to start this work, and we have to make sure that we’re respectful and meeting them where they’re at in terms of the information that they feel comfortable sharing.

JR: Well, that’s why I think mentioned the thing before because the information that was provided was never revealed to anybody else. It was put together, as I said, in aggregate so that people could use it as a comparison tool. It was distributed in a newsletter. This seemed to me that that could be a good model. And I’ve told Howie “Let me know if there’s anything OffBeat can do to help you because I know the musicians and I know the venues. Anything we can do to help you would be great.”

I was thinking about doing a survey of venues to find out just with how they did during Jazz Fest. If they did better than the year before or worse, and what their challenges were, to find out. We need to do something on a local level that could coordinate with what you’re trying to do. That’s why if there’s anything that you want to provide to me that would help you gather information for your data set, let me know because I will try to help you.

SP: Thank you. We’ll take you up on that. I’ll follow up after the conference.

JR: Are you having that same problem getting people to participate and understand that if they work together they’ll have more clout and do better overall?

SP: I would say we’re not having that issue in terms of the desire to get together. I would say that the amount of camaraderie and collaboration that the pandemic created between independent venues is inspiring.

What we are seeing is that it’s harder to take the time to be as active and connected as they were during the height of closures during the pandemic because now they need to rebuild their businesses, and make sure that they keep their doors open for their families and for the fans and for the artists and for the staff that work in these venues. The desire is still there. The energy is still there to want to work together like independent stages and independent venues have never worked together before. But the challenge is to find time, and again, you’ve heard me say this previously in this interview, we have to meet them where they’re at. We have a lot of people that come to our conference, and 500 plus venues are going to be represented in New Orleans at our conference. Basically that is one path, but it’s also expensive to fly somewhere. It also takes time to come to a conference for two or three or four days.

We realize that’s why we have to create virtual opportunities throughout the year for them to connect with their peers and talk out issues and learn from each other and develop best practices and also collectively advocate for the industry. That’s what we aim to do throughout the year in between our conferences.

JR: Are you planning on trying to establish maybe a statewide chapter or something like that?

SP: We have 26 chapters across the country.

JR: Okay. Do you have a chapter in Louisiana?

SP: Yes, we do.

JR: In New Orleans?

SP: We have a chapter in Louisiana. There’s state or region chapters. We have some local and city and community-based organizations that we work with, and we share many members with them. A great example is there’s a venue association in Nashville, there’s a venue association in Los Angeles, there’s a venue association in Northern California, there’s a venue association in Portland, Oregon, there’s a venue association in Indianapolis, all of which work with us very closely. Many of the leaders of those organizations are leaders or chapter leaders in our organizations, but they’re technically not chapters of NIVA even though we work very closely with them.

JR: Would that be a goal: to increase your chapters? How do you establish a chapter by the number of venues from that area or something?

SP: It’s where there’s a desire to collectively work together in a regional or state level. We’re still figuring out the best path forward for chapters and states and regions, so more to come on that.

JR: You have to give people a carrot and hold the carrot out as an incentive: “This is going to benefit you. You’re going to get all this data and information, and you’re going to get access to all these benefits.” How do you throw the carrot in front of them to get them to understand and to participate? One of the things I’ve always thought is that carrot will answer the question, “What’s in this for me?”

You always have to look at it that way too because that’s how a lot of people think. In this town, there are. Because people who, like I said, particularly on Bourbon Street and it’s getting their way on Frenchmen, where they don’t care. They really don’t care about if anybody’s open or if the guy down the street is open, they don’t care. They’re looking at their own stuff, and that’s all they care about. I don’t know if it’s like that in other places, but how do you correct that mentality that if we work together we’ll actually be able to accomplish some good things for everybody?

SP: I think the mentality is there at NIVA, it’s just finding the time and the resources to be able to connect. What information can be most helpful?

I will say the entire conference is a celebration of the New Orleans venue and promoter and independent music community and Louisiana and independent stages as well.

We’d love to have as many folks there from the community as possible. Our conference is very affordable compared to other music industry conferences. I don’t know another music industry conference focused on live music that is under $900 to go. We are a third of that for our members, so I think that there’s a tremendous opportunity here to have an accessible space, whether you’re interested in live music or you’re actually working in live music to come together and learn what we can do together.