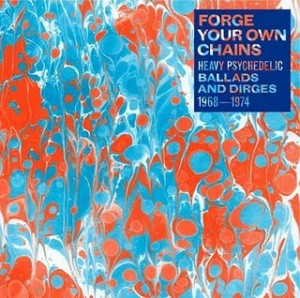

I have two theoretically cool new CDs on my desk, Earthology by the Whitefield Brothers and Forge Your Own Chains: Heavy Psychedelic Ballads and Dirges 1968-1974 (both on Now Again Records), a compilation that is exactly what it says. Both discs bring me a significant amount of pleasure, the first being new music made to emulate obscure world soul/funk, the second being an actual collection of late ’60/early ’70s obscurities. But the pleasure comes largely by contrast, not because of any intrinsic value. They sound great compared to contemporary pop, rock ‘n’ roll and hip-hop, all of which are so concerned with the “now” sound that they seem antiseptic, whereas these albums, like garage rock classics, have an evocative sound. You can date a host of obscure funk singles to the year if they have the compressed fuzztone Ernie Isley used on “Who’s That Lady?” for instance. And the obscure tracks often feature artistic decisions that make the recordings more human than current celebrity-obsessed rock does. It would seem, for instance, like someone would tell Top Drawer’s Steven Geary that “Song of a Sinner” (from Forge Your Own Chains) isn’t enough of a song to sustain eight minutes, no matter how sincerely he repeated verse after verse. But no one did, and the track’s engaging in its way. The pleasures are largely meta- though, stemming from the world around the track rather than the track itself. In this way, the pop/rock/soul/funk obscurities are akin to folk art, which is ultimately more about the artist than the art.

I have two theoretically cool new CDs on my desk, Earthology by the Whitefield Brothers and Forge Your Own Chains: Heavy Psychedelic Ballads and Dirges 1968-1974 (both on Now Again Records), a compilation that is exactly what it says. Both discs bring me a significant amount of pleasure, the first being new music made to emulate obscure world soul/funk, the second being an actual collection of late ’60/early ’70s obscurities. But the pleasure comes largely by contrast, not because of any intrinsic value. They sound great compared to contemporary pop, rock ‘n’ roll and hip-hop, all of which are so concerned with the “now” sound that they seem antiseptic, whereas these albums, like garage rock classics, have an evocative sound. You can date a host of obscure funk singles to the year if they have the compressed fuzztone Ernie Isley used on “Who’s That Lady?” for instance. And the obscure tracks often feature artistic decisions that make the recordings more human than current celebrity-obsessed rock does. It would seem, for instance, like someone would tell Top Drawer’s Steven Geary that “Song of a Sinner” (from Forge Your Own Chains) isn’t enough of a song to sustain eight minutes, no matter how sincerely he repeated verse after verse. But no one did, and the track’s engaging in its way. The pleasures are largely meta- though, stemming from the world around the track rather than the track itself. In this way, the pop/rock/soul/funk obscurities are akin to folk art, which is ultimately more about the artist than the art.

The problem with Forge Your Own Chains and to some extent the Numero Group reissues is that the songs themselves are often weak – imitations of stronger artists whose success they wanted a piece of. In the same way, when I hear Nuggets, I don’t hear rock ‘n’ roll rebels. I hear bands doing their best to mimic the Beatles, Rolling Stones and to a lesser degree the Kinks, hoping that doing so will lift them to the big time, too.

The ironies in this discussion are numerous, the first being that the sounds that are fetishized by cratediggers were the “now” sounds when the songs were first recorded, and in 20 years, we’ll hear the identifying traits of music from the late 2000s as easily as we can date ’80s dance music by the keyboards and drum machines used. As such, the recordings and artists used to illustrate the emptiness of contemporary music (by contrast) really were no different; they just had access to different technology, and unlike many of today’s successful artists, they wrote generic songs that are only memorable because of their sound or the odd decisions that they made that further worked to keep them from ever reaching their goals.

Earthology‘s a slightly different issue because it’s new music that aspires to sound old and odd, but the curious feature is the way it does so by recording grooves and hooks that recall – if that’s the right word – those on recordings whose primary distinguishing features are their sonic oddity and artistic conventionality. In short, the Whitefield Brothers seem to have worked to create something that is generic in a crucial sense, which seems like an artistic dead end.

Just as every generation has to discover the garage rock classics for themselves, I suppose the technology now makes it possible for this and future generations of funk and R&B fans to step into the less intimidating shoes of those whose albums are their prized flea market and yard sale finds, but that doesn’t make the results any more rewarding.

I’m glad I have Earthology and Forge Your Own Chains; both fit into my life because I can work to them without being distracted, but when I stop to pay attention, there’s something to reward my attention. And, I like the sounds that these albums fetishize; I like sounds that come with roots and hint at the world around them. But because the thing at the center of it all – the song’s idea – tends to be thin, it’s hard for me to be passionate about them.