Sublime gets no respect except from the people who love them, of whom there are many. OffBeat intern Patrick Rulh is one of those people who found Sublime crucial. Here’s his take:

I can still remember the first time the name “Sublime” made its way to a permanent home in my impressionable seventh grade brain. At 13, I made a comment in gym class about a Sublime T-shirt worn by some older kid with a head full of dreadlocks, cut-off jean shorts, and a tattered pair of Vans.

“Dude, I live my life by Sublime,” he said. I assumed that meant he probably liked to smoke two joints in the morning and perhaps another two at night, but I knew he meant more. Sublime became larger than life in my mind, something special on a level with Bob Marley and the Wailers. I was young, broke, and probably suffering from ADD, so it wasn’t until a year or two later that I actually got the chance to really experience Sublime. I was at a Best Buy with my dad, preparing for a road trip from New Orleans to Houston, when I came across their Greatest Hits album on the shelves. I grabbed it to show him.

“Oh, Sublime is great,” he told me, and we threw it in the cart. “Great” was an understatement. For me, Sublime was one of the greatest bands of all time.

Brad Nowell’s voice struck me first. It was so smooth and soothing with such wide range. Between his high-pitched angelic moans, deep ad-libbed grunts, and volatile punk attack, every word out of his mouth exuded passion and emotion. Sublime’s rhythm section of bassist Eric Wilson and drummer Bud Gaugh was also a force to be reckoned with. At that point, the only time I had heard bass on the forefront like that was in the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Bud and Eric were my Sly and Robbie.

The band was like nothing I had ever heard before. I fell in love with the upbeat classic ska jams “Date Rape,” with its combination of the blaring horns and at once serious and humorous lyrics. As a kid entering high school, I embraced the rebellious punk rock climate of many of the songs and admired the way the band traveled gracefully between genres within single songs. “Seed” starts with a screaming, thrashy intro, moves into a slow, calm reggae groove that almost immediately speeds up to ska, and then back to punk, bridged with a wailing guitar solo that screams pure rock ‘n’ roll. Songs like “Doin’ Time” and “April 29, 1992” tickled my hip-hop fancy with their Mobb Deep and Snoop Dogg vocal samples mixed with turntable effects and reggae rhythms that, again, were unlike anything I had ever heard.

I grew older, and my appreciation for Sublime only grew. I purchased the extensive, two-disc Gold collection and later the even more encompassing Everything Under the Sun. I started to take closer note of the things Sublime did that made them so brilliant in the eyes of many. They developed a sound that I think of as dub rock, which can be heard on tracks such as “89 Vision” and “Pawn Shop” where live guitar sounds mix with lyrics accompanied by drum and bass breaks complete with shimmering cymbal crashes and snare drum hits echoing like .22 shots into the night. Sublime was an obvious influence on such current reggae/rock bands as Slightly Stoopid, Rebelution, and up-and-comers the Holdup, who are signed to the appropriately named Dub Rock Records.

Critics of the band will argue that many of Sublime’s most popular songs were covers or contained samples and borrowed lyrics. I’d argue that Sublime’s habit of reproducing classic tunes only added to their brilliance. They covered songs in a way unlike any other, often adding verses and alternate arrangements to make the covers their own. For instance, taking the drums from James Brown’s “Funky Drummer,” mixing them with reggae keyboards and adding an original verse for the cover of Greatful Dead’s “Scarlet Begonias” is pure genius.

One DJ has described Brad Nowell and Sublime as “a vessel of beautiful music for a whole new generation.” Brad’s allusions to lyrics of other artists was a way to resurrect powerful messages and help them live on. He had a knack for incorporating others’ lyrics with his own as a way to help him tell a story or get a point across. The way they borrowed lyrics and melodies and blended them with original compositions was, for me, a far greater nod of the hat than an out-and-out cover.

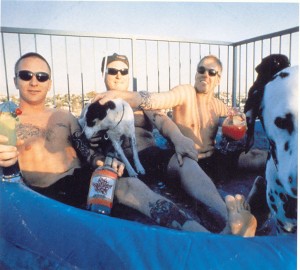

Nowell’s lyrics were always humorous, always rebellious, and no matter how starkly adverse his words were at times, they always came out with a positive tone. Part of me feels like that phenomenon is a result the amount of love within him, which emanated naturally whenever he used his voice. In fact, love might have played a bigger role in Sublime’s lyrics than humor, reality, or rebellion. Whether it was the verses of “Doin’ Time,” “Sweet Little Rosie,” or “’89 Vision” tinged in hopeless romanticism or dedications and references of affection for his beloved companion, Lou Dog, love was always present.

Sublime was a trio of regular dudes from Cali that didn’t give a fuck. They were out to live life, have a good time, and make good music. Lyrics like, “Load up the bong, crank up the song, let the informer call 911!” celebrated their free spirit status. I think back to my gym class buddy and what it means to live life by Sublime. They never confined themselves, and they united cultures and sounds through their music. Though the band’s life with Nowell came to a painful, premature end, its spirit carries on, and future generations will continue to realize that there really is no other band like Sublime.