Stepping into the lobby of New Orleans’ Orpheum Theater before the memorial service for Malcolm John Rebennack Jr., a.k.a. Dr. John, I heard his recording of Allen Toussaint’s “Life” playing from inside the auditorium.

“Mother, mother,” Rebennack laments in grit-and-gravelly tones, “I have felt the mark of 10,000 thousand teeth. I done seen my body lying stiffly at my feet, as I’ve seen my soul, creeping out of my chest.”

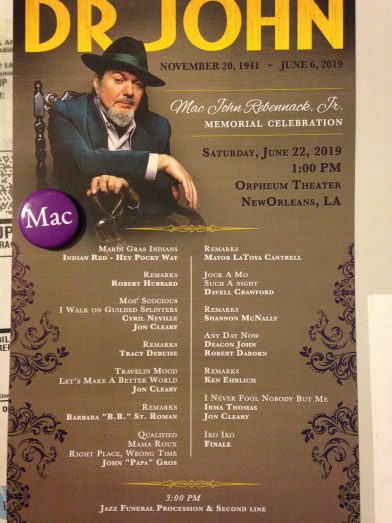

A six-time Grammy winner, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee, one-of-a-kind New Orleans musician, character and cultural torch bearer, Rebennack died June 6. In November 2015, he’d been among the mourners in the Orpheum Theater paying their respects to his contemporary, Allen Toussaint. A fatal heart attack at 77 years old is one of myriad things the two New Orleans music masters have in common.

Pianists, songwriters, producers and singers, Rebennack and Toussaint are characteristic products of hometown and, in the same breath, off-the-charts unique.

Pianists, songwriters, producers and singers, Rebennack and Toussaint are characteristic products of hometown and, in the same breath, off-the-charts unique.

Toussaint—one of the many cherished musical friends Rebennack called “my pardner”—produced Rebennack’s sixth album as Dr. John, 1973’s “In the Right Place.” Recorded in New Orleans with the Meters, the album’s songs include Toussaint’s wise and soulful “Life” and Rebennack’s Top 10 hit, “Right Place, Wrong Time.”

Unlike the public memorial held at the Orpheum for Toussaint, Rebennack’s farewell was for family and invited guests only. Guests included Meters guitarist Leo Nocentelli, singers Charmaine Neville and Al “Carnival Time” Johnson and Freddie Staehle, drummer for the Dr. John albums “Gumbo,” “The Sun, Moon & Herbs,” “Goin’ Back to New Orleans” and “Television.”

During the memorial’s musical performances, a band comprised of musicians who’d worked with Rebennack through the years—bassist Roland Guerin, guitarist Renard Poche, drummer Herman LeBeaux Jr. and percussionist Kenneth “Afro” Williams—backed an all-star slate of local talent. Singer-pianists Jon Cleary, John Gros and Davell Crawford and vocalists Irma Thomas, Deacon John Moore and Cyril Neville performed many of Rebennack’s signature songs. They put their hearts in it, but no one can do the songs the way Dr. John did them his own special self.

The closed, shiny wooden coffin lay just below the edge of center stage. Two photos stood on each side of the casket, one an image of the young Mac Rebennack, a guitar player who loved working as a producer, songwriter and sideman in the studio. The other portrait—shot during a photo shoot for Rebennack’s 2006 Johnny Mercer tribute album, “Mercenary”—showed Dr. John leaning forward, arms crossed, left hand gripping the handle of one of his ever-present walking sticks.

A towering floral arrangement, the only flowers in the place, stood on top on the casket. Other than the latter arrangement and a display of black-and-white flowers arranged to resemble of a piano keyboard, the Orpheum stage and floor were conspicuously flowerless. In lieu of flowers, the Rebennack family has requested donations be made to one of Dr. John’s favorite organizations, the New Orleans Musicians Clinic. “Ain’t an easy life playin’ music in New Orleans,” Rebennack once said. “An’ what you all been puttin’ in the tip jar is nice, but it ain’t gonna pay no medical bills.”

Quint Davis, producer-director of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, served as the memorial’s emcee. Speaking in a voice unsteadied by emotion, Davis appeared on stage at the ceremony’s start but then continued his narration from backstage through the rest of the program.

Dr. John loved the Mardi Gras Indians tradition. The afternoon’s first musical selections featured big chiefs—including the Golden Eagles’ Monk Boudreaux, FiYiYi’s Victor Harris, the Wild Squatoulas’ Howard Miller and White Cloud Hunters’ Charles Taylor—performing the Indian songs “Indian Red” and “Hey Pocky Way.”

Between the memorial’s music, a succession of speakers shared their thoughts and memories of Rebennack. Robert Hubbard, a first cousin from Baton Rouge, was the only family member who spoke. Other speakers included Tracy Deruise, a friend for more than three decades who knew nothing of Rebennack’s musical activities for years. Deruise didn’t find out about his friend’s musical prominence until Rebennack gave him a pair of tickets to a Dr. John show at the House of Blues in New Orleans.

“My sister was with me because my old lady wouldn’t go,” Deruise said. “My sister say, ‘Well, where ya’ friend?’ I say, ‘I guess he’s in the back.’ When Doc came out on the stage, I say, ‘That’s him, right there!’ My sister punched me and said, ‘Stupid! That’s Dr. John!’ I say, ‘I know him as Mac.’

“I’m just trying to tell you the kind of person he was,” Deruise explained. “He met a kid like me, 22, 23 years old, and brought me into his life. We talked about a lot of things. I got to meet a lot of entertainers. I’m really gonna miss him. He’s a part of my life and my family’s life. He watched my kids grow up.”

Another speaker, Barbara “B.B.” St. Roman, worked with Rebennack from 1983 to 1993. After becoming a fan and volunteering to help with him with this, that and the other, she became his official road manager.

“In the 80s, we were both living in New York City,” St. Roman said. “I watched him play at the Lone Star Café in New York and fell in love with his music. But I soon found out that no one was helping him out much at that time besides his booking agent. Through my organizational skills and helping him, I had the honor of being around a true New Orleans legend, a genuine char-actor. And I certainly got a real edumacation.”

When St. Roman met Rebennack, he was mostly playing solo gigs. “In the early ’80s,” she said, “his dream was to one day be on the road again with his own band, especially his own New Orleans band. It took a few years, but eventually his dream came true. I never saw him happier.”

Singer Shannon McNally and Rebennack co-produced her album of songs by their mutual friend, singer-songwriter and Dr. John contemporary Bobby Charles.

“Mac had a very strong respect for death,” McNally said during her emotional eulogy. “That’s why he lived like he did. He had one foot in the afterlife and one foot here. … He was really a high holy man, a prism that refracted and redacted and resorted the light. The kind of prism that you could have your whole worldview go through.

“He once told me I sang just like Patsy Cline and Otis Redding at the time. I’ve never needed another critical review. I don’t really know how you do that, but I’m awful glad I did it and that I did it for him. … my mentor and the slammingest friend a girl singer could ever have. Hey, Mac. I’ll see you later, alligator.”

Ken Ehrlich, longtime executive producer of the Grammy Awards broadcast, recalled his 45-year friendship with Rebennack.

“To me and many others, Mac was the voice of this city,” Ehrlich said. “Whenever we knew it would be a while until we’d see each other again, we’d shake hands, give each other a hug. And then I’d hear that gravelly growl, ‘God bless yo’ ass.’ Well, Mac, thanks for a lifetime of making the world a better place—and God bless your ass.”

Irma Thomas sang “I Never Fooled Nobody but Me,” the Rebennack composition he taught her 15 minutes before she recorded it. Thomas’ and Rebennack’s connection dates to him playing guitar for her debut recording, 1959’s “(You Can Have My Husband but Please) Don’t Mess with My Man.”

“Once again, I’m here to send off a friend,” Thomas said on the same stage she bid adieu to Toussaint. “We don’t send our folk off in sadness. We send them off in happiness.”

Pallbearers carried the coffin outside into the bright, broiling summer afternoon, placing it in a horse-drawn hearse surrounded by thousands of onlookers waiting to participate in the second-line procession. Two horses—one black, one white, side by side like piano keys—pulled the carriage from the Orpheum Theater to Canal Street, Basin Street and St. Louis Street. Members of Rebennack’s family walked behind in the main funeral procession line while the Kinfolk Brass Band and dancing members of the Young Men Olympian Jr. Benevolent Association led the throng. The New Birth Brass Band and Mardi Gras Indians and Baby Dolls also joined the joyful, nearly chaotic celebration of a blessed New Orleans life.

I suspect Dr. John would think this, his final encore, was correct.