New Orleans better be ready for some high-octane rock and roll shows this weekend when the Drive-By Truckers return for a two-night stand at Tipitina’s. Truckers’ frontman Patterson Hood promises to run his “well-oiled” machine loud and late into the moonlight. “We’ll hit it with barrels blazing both nights,” he says.

Hood calls Tipitina’s “another home” for the band. But, of course, these southern gothic storytellers are road warriors from Athens, Georgia, with roots in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where Hood’s father worked with—to name but a few—the Rolling Stones, Percy Sledge, and Aretha Franklin.

American Band, DBT’s 11th studio album, has earned international acclaim for both the quality of the sound and the topicality of the songs. The band considered taking a hiatus before this concept album coalesced around two political songs. First, Hood wrote “What It Means,” about Stand Your Ground laws and racial police killings, and Mike Cooley responded with “Ramon Casiano,” about the Mexican boy murdered by a future NRA leader.

While the Truckers are singing about a new cast of criminals, plenty of old themes and characters make appearances, whether in Hood’s recently published fiction or in the present lyrics. No matter the narrative, however, Brad Morgan still drives the rhythm from behind the drums and their guitars still rip full-throttle. We have two nights with this great American band, so don’t miss out on these rock shows—it’s what they do best.

Y’all are bringing the “Darkened Flags” tour to New Orleans Easter weekend.

Right, I can’t wait. We’re excited to be back at Tipitina’s. It’s been a little while since we’ve played there, and it’s like another home for us, because we’ve played there so many times over the years. But we’ve been at a few other different places the last three or four times we’ve been in town, so it’s gonna be really wonderful to get back there for two nights. And it’s always better if we get a couple nights to stretch it out.

So with a double-header, the Drive-By Truckers won’t take it slow one night?

[laughs] Naaa. We’ll hit it with barrels blazing both nights for sure. It’s been a really great tour. We’ve been essentially on tour since July, and I think the last couple legs have been the best yet on it. The band’s in a really good place, running on all cylinders as they say. It’s pretty well-oiled by now because we’ve been rocking this thing pretty hard for a while now.

And the national press has recognized that in this new record. Was this a deliberate concept album like Southern Rock Opera (2001) or was it more serendipitous that you and Cooley wrote these songs to fit the times? Tell us about the creative process that led to American Band (2016).

I think it was like you said. The first song I wrote for this album was “What it Means” in the fall of 2014 when we were out touring a still really new record. English Oceans (2014) had only been out for a short time at that point. And we’d planned on—after touring English Oceans—on taking a little time, sort of a break, maybe a hiatus. That had kind of been a plan. I didn’t write it for an album or with a specific, uh—

Goal or plan in mind?

Yeah, I really just wrote it to deal with my own feelings about what it’s about. It was eating at me and often my way of dealing with things is to just write about it. I was trying to make sense of things that didn’t make sense to me. And I wrote this song as a kind of questioning: Can we not rise above this? Can we not get past this bullshit?

Our country’s demons with race have been our Achilles’ Heel since before its creation. The tragic flaw in the initial creation of the country was them not being able to end slavery at the time. It came back to haunt us in a really big way “four score and seven years” later [laughs]. And yet here we are 140-160 years later still dealing with the same fucking bullshit. And this whole notion of this fear of the other, you know? Whether it’s people who look different or pray different or fuck different, or whatever. Our country is obsessed with this boogeyman who’s gonna come into our house and rape our daughters. It’s a national obsession, and I wrote that song as a questioning of all that.

So how’d y’all come to record it?

I didn’t have any idea it would be something the Truckers would record. You know, I figured I’d throw the lyrics up on Facebook or something, or record it on my phone with acoustic guitar and throw it up on the internet, and be done with it. But it kept happening. And at one point I played the song for the band and they were thrilled about it.

Cooley responded by playing his brand new song, which happened to be “Ramon Casiano.” And at that point something was just like, “Oh shit, I guess this is where we’re both headed.” Within a matter of hours, days, weeks after that we came to the conclusion that we weren’t going to take a hiatus, and we were gonna make this record and make it sooner than later. And maybe try to get it out before the election. And maybe go out and tour in the fall of 2016 playing these songs leading into an election.

Once we decided that, the rest wrote itself. I’d send Cooley a song, he’d send me a song, and then we’d send it to the other guys. Then when we’d see each other, we’d work a song up in sound check, and some we just worked up in studio when we were making it. We made the record in six days. It’s the fastest we’ve made a record since Pizza Deliverance (1999). The difference being is with Pizza Deliverance, you know, five days is the only money we could come up with to make that record. With this record, we figured we’d take two or three weeks to make. But six days, like, well shit, it’s done. Let’s take this other time we have to mix it and get it out there.

It was magical. The band’s never been in a better place musically and personally. The idea of us putting it out back-to-back so soon after the last one, and then going out and spending the next year or so working it isn’t at all daunting because we’re all having fun together. We’re having a really good time as a band right now. And I think the shows reflect that. The word of mouth out there saying the band is really good right now [laughs] and that we’re obviously having a good time with it.

You mention the national obsession with the other. I hear it some in “Ever South” when you mention your “drawl”—

Sure.

It’s a sort of song-sized James Michener epic history of the Scots-Irish people, ostracized to Appalachia and then spread beyond. Have you ever felt like the other in the South as a progressive-thinking white man? Or in Portland because of your accent?

A little yes and no on all of it. Because of the accent and the fact that a lot of our songs take place in the South, you know, we’ve at times gotten typecast as a southern rock band. I’ve never thought of us as that. We did a record about a southern rock band, but I’ve never thought of us as that. I’ve always thought of us as a rock and roll band. And, well, rock and roll originated in the South and really close to where I grew up. I mean, Sam Phillips is from my hometown, Florence, Alabama.

And just a couple hours southwest of you is Tupelo, Mississippi where Elvis grew up and a little further is where the blues was born.

It’s like barely an hour from my hometown, Tupelo—straight west. It’s really close, and Memphis is two and a half hours from my hometown, and, of course, Nashville is two hours from my hometown. So it’s all in my neck of the woods and I’ve just always thought of us as a rock and roll band. Part of what I like about rock and roll is that it’s a big enough umbrella to fit a lot of the other subgenres under it. Whether the subgenre of southern rock or hip-hop or punk or, you know alt-country or whatever. Our band has dabbled into and been influenced by a little of all of those, you know—country soul. So that’s always been part of what we do and who we are. I’ve never thought of us as only one aspect of it.

And doing what I do for a living, overall my southern accent—it might be different if I were a doctor or an attorney, or it might not, I guess—but for what I do, I’ve always been proud of the accent. It gets used badly a lot [laughs], but I try not to use it badly. If they’re making a movie and there’s a bigot sheriff, he generally has a southern accent. I’m aware of that, so I’ve always been kind of proud that I stand for something else and that I can talk about it and still have my north Alabama twang.

After a terrorist murdered nine unarmed people in a Charleston church, you wrote in the New York Times that southern heritage is more than the Confederate flag.

I feel very strongly about that, yeah.

You said we should honor our forefathers by moving on from their prejudices and building upon the diversity, art, and literary traditions we inherited from them. Is that what you’re doing with this album, rising up for southern art?

I hope so, yeah. That’s definitely part of our intent when we named it American Band, was that and getting away from being called a southern band. We’re an American band, you know? The South is still part of America. And sometimes for better and for worse—and from both ends of that equation.

Tell us how you wrote “Guns of Umpqua.” How’d you balance out the naturalism of hiking with the murder at school?

I had just moved out here to Portland when the shooting happened at Umpqua Community College. In our move, we spent three weeks driving cross-country and turned it into a little bit of a vacation.

And your kids are old enough to enjoy that?

[laughs] Yeah, I don’t know how much they enjoyed it. They were, theoretically anyway. It was kind of hellish [laughs]. Some of it was really fun. Some was really rough. But the last night before we got to Portland, we actually stopped for the night in that town. Is it Roseburg, I think? In the Cascades, a small town in southern Oregon. It happens to be the town where Umpqua Community College is. It was an early fall day, a beautiful day, a lot like today is—it’s really pretty today. It was a gorgeous sunny day, and I was sitting on my front porch, drinking my coffee and reading the news like I do every day that I can and, uh, the news came up that a shooting was happening. I thought, “Wow, that’s the town we spent the night in.” So I could picture the town, and I could see the blue skies. Remember how like 9/11 was such a beautiful day?

Yeah, I remember 9/11’s blue sky.

It was a gorgeously sunny day. I remembered that. You know, you wake up in this pretty place and the sun is shining and birds are chirping and—what makes you wanna go do something terrible to end that? That’s where I came from with that and it basically wrote itself. I think I thought about it for about three days, just kinda pondered that idea, and then wrote it on an airplane to Atlanta to meet the band to go do a tour.

So do you always write off sudden inspiration like that? Or is there ever a turn of a phrase you flex out? Or a melody? What is it typically?

Typically, it’s kind of all of the above. Typically, it might be an idea I’ve thought about for a day or a year, or in some cases, years, depending on what it is. But what causes the actual song itself to happen is generally pretty quick. I generally write them quick. I kind of consider that other time—I call it “percolating.” The idea may percolate for a really long time, but the actual writing of the song itself is usually under an hour.

Many of your songs are narrative stories with characters, and last fall you published your first fictional short story, “Whipperwill and Back,” a character-driven crime story in the noir collection, The Highway Kind: Tales of Fast Cars, Desperate Drivers, and Dark Roads (2016). I loved it.

Well, thanks.

And I recognize the Chris Blake Pontiac in the story from an earlier song, “The Great Car Dealer War” from The Finer Print (2009). Is that the same idea “percolating?”

Well, yeah, they are kind of kin. You’ve got an astute memory on that. You get brownie points for that. The character driving the car in the story, Charlie—he might be the arsonist in the car dealer war. They are sort of related. I’ve thought about writing short stories about all those various characters and tying it together to tell the bigger story. It’s all tied into what they call the “redneck mafia” or the “state-line gang.” All those songs from The Dirty South (2004) came from those stories. And “The Great Car Dealer War” was an outtake from that album. So all that is kind of interrelated, and that might be something I do at some point in the future. I still ponder the notion of writing a book at some point.

In “Darkened Flags on the Cusp of Dawn,” an important verse is “We should light out for the trees and the great beyond, light out for the love of thee.” How often do you get outdoors?

I don’t do it as much as I should, I know. That was part of moving out here. The heat of the summer didn’t agree with me in the South, and the older I got, it got worse. It got to where it became a pretty big issue where four or five months of the year—unless I had to get outside to work for something specific like to play a show—it was really hard to drag me outside. I would go outside and be miserable. It would shut me down. That was kind of part of our moving up here, to get me in a place where the summers agreed with me. I’ve probably spent more time outdoors—even with the rainy season—out here since I’ve lived here than maybe the last four or five years combined, or decade prior to moving here.

It’s probably made me enjoy the South more, too, when I come home to it. I’m not caught up in the day-to-day things that were pissing me off. Now when I go home, I really get to enjoy visiting my friends or whatever I end up doing when I’m in Athens. Or when I’m in New Orleans. I adore New Orleans. I think it’s been good overall for my mental health, which is always a questionable thing at best around here [laughs].

Sometimes going away from home enhances your appreciation for home.

For sure. Like I said, I couldn’t have written “Ever South” if I hadn’t moved. I had to have a little bit of distance to be able to write something like that. And that’s probably the song I’m proudest of on the new record as far as my writing goes, as far as my songs go.

You’ve covered Tom T. Hall songs, written some for George Jones and Lynyrd Skynyrd, and played with Booker T. and the MGs. Who else has influenced your songwriting?

Too many to name. I’ve been picking up some of those Howlin’ Wolf re-issues, really enjoying some of those. I’ve been playing my Chuck Berry records since he passed away, pulling those out and playing them for the kids, like, “This is where it all came from,” you know? I have a pretty crazy record collection because I’ve been collecting vinyl since I was eight years old.

How much vinyl’s in your collection?

I’m getting close to 4,000. Yeah, around 4,000. I’ve just recently been able to put it all back together. It’s been in disarray the past few years from the move and some were boxed up. I just recently got a really nice new turn-table. So I’ve been really enjoying getting to spend some time with that since I’ve been home.

Have you been reading anything recently that’s influenced your current writing?

On the last album, English Oceans, there’s a song that’s directly influenced by a writer named Willy Vloutan, a Portland writer, and he had a book called The Free. And there was a character called Pauline Hawkins. I wrote a song on that album about her. I’m always reading something or another. Right now, I’m reading George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo.

That’s his first novel, right?

It is his first novel, and, boy, it’s a handful, too. It’s great but it’s difficult. I’m not far enough along into it to where it’s really making sense yet. It’s a lot to grasp, but it’s something else. He’s one of my favorite authors. But I just finished—on the plane coming home from Europe—Fight Club, which, I’ve seen the movie and met Chuck Palahniuk pretty recently because he lives in Portland and we have some mutual friends. Oh my God, it’s great. It’s fantastic. I’d always liked the movie but the book is way, way better. That was a fun read. I’m also reading For Whom the Bell Tolls by Hemingway, which is the last of his great novels that I hadn’t read. I’ve pretty much read all his major works over the years but I’d never read that one. It’s phenomenal.

Who are you listening to? You used Futurebirds and Lera Lynn in your song to preserve downtown Athens. Who are some other bands on the rise?

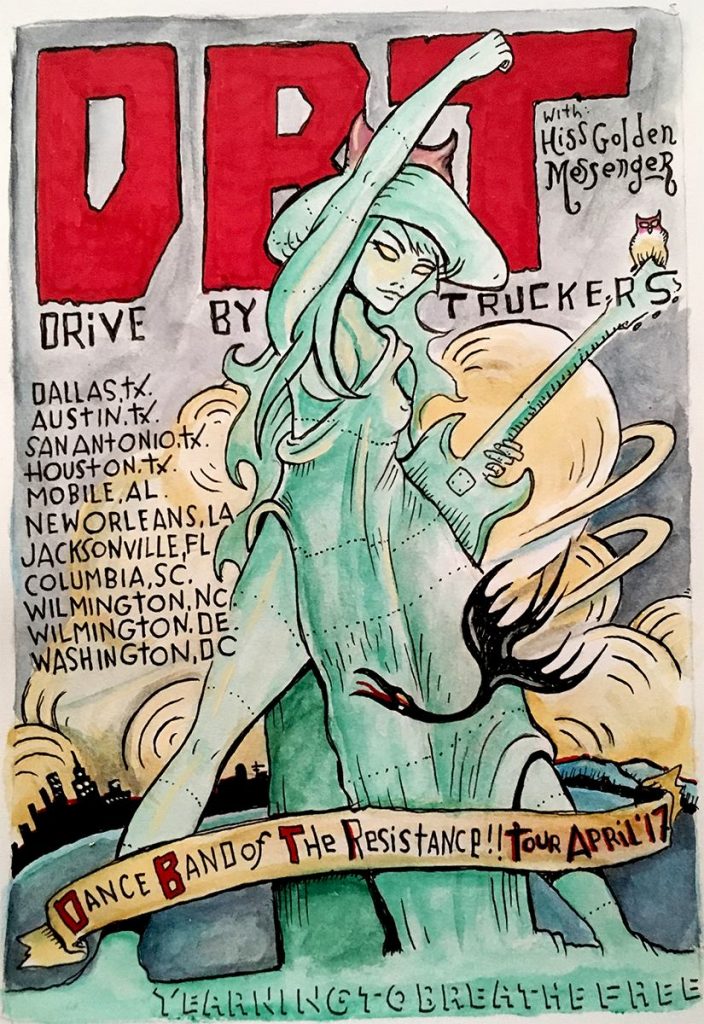

That’s right, yeah. Well, the band touring with us when we come to New Orleans, Hiss Golden Messenger, their record’s been one of my favorite records of the last year. I’m really excited to be out playing with them. I really like the Car Seat Headrest record, Teens of Denial, is great. I just got the new Spoon record and it’s great. I’m still listening to the Frank Ocean Blonde record, and A Tribe Called Quest’s record, and Run The Jewels 3—that’s great. And Hurray for the Riff Raff, and she’s based down there New Orleans, isn’t she?

Yeah, Alynda Segarra is based down here. She told me over Mardi Gras how much she respects y’all and loves your new record.

Really? I love hearing that. That absolutely makes my day because it’s so mutual. I’m loving that new record, The Navigator. My wife’s a little obsessed with it. And my daughter, too. My daughter’s loving that record. Segarra’s a great role model, and I’m glad there’s someone like her out there for my daughter to listen to and kind of look up to because she’s very inspiring and such a talent. That record is phenomenal and is already a contender for record of the year. The year’s pretty young but it’s phenomenal. We actually played a show together one time, me solo with the Alabama Shakes. That was the first time I ever heard them. Beyond that, I didn’t know she’d even know who we are. So that makes my day.

Drive-By Truckers will perform at Tipitina’s on Friday, April 14 and Saturday, April 15. Hiss Golden Messenger will open both nights. Tickets for the shows are available here.