Poet, political and marijuana activist and writer John Sinclair has died of heart failure at the Detroit Receiving Hospital on April 2, 2024, he was 82.

John Sinclair was a friend and an important contributor and voice in OffBeat Magazine. The first issue of OffBeat, July 1988, Sinclair wrote a brilliant piece on Mardi Gras Indians with this introduction: “Urban American culture begins and ends in the street, where wave after wave of ethnic immigrants has crested, broken, and, largely, dispersed into the vast suburban landscape of metro America.” The article, one of the first to document the unique street culture in New Orleans and of the Mardi Gras Indians, continues: “In the streets our cultural heritage will live and grow, our music will swing with vigor and intelligence, our imagery will be ripe with oranges, hot tamales, cans of pop, yellow trousers, a sea of faces, legs and shoulders—brimming with humanity and pulsing to the many vigorous heartbeats of our citizenry.”

John Sinclair contributed a monthly column in OffBeat called “Crescent City Bounce.” In the column, Sinclair revealed lesser-known information, such as the plethora of clubs presenting live music in Treme, which, at the time, was not covered in the media elsewhere. Sinclair also wrote a great cover story in October 1993 on Johnny Adams, with an iconic cover painting of the “Tan Canary” by California artist George Buck.

In May 1994, Jazz Fest celebrated its 25th anniversary. The issue contained two fabulous interviews by Sinclair, one with Harold Battiste and the other with Dr. John. In the Dr. John interview, Sinclair asks “I’m enjoyin’ your new record immensely. That rap number, ‘Shut The Funk Up,’ put me in mind of that record you did with Duke Bootee.” Dr. John’s reply: “Yeah, I like that we done that, man. That kid Anthony Keidis [from the young punk funk group The Red Hot Chili Peppers] is cool, you know? I gave him a tape with me talkin’ about Otis Redding and whoever I thought about as my inspiration for funk, and he did what I told him. I said, write about what inspired you, and he used his own cats that inspired him-and a lot of ’em inspired me too.”

The February 1996 issue of OffBeat yielded Sinclair’s hilarious exchange with Ernie K-Doe. Sinclair congratulates K-Doe on his recent marriage [to Antoinette K-Doe] and asks: “everybody’s got to be after you now about having a new mother-in-law.” K-Doe’s response: “The first mother-in-law I had, I didn’t know about her, that she was that particular way. That’s why I could sing that ‘Mother-In-Law’ song. But my new mother-in-law, I know all her feelings, and I’m gonna write a song about her, because you look for the little things that you learn from your mistakes. That’s how you get great, by your mistakes. All I wanna do, is do what’s right now. So, I can’t go wrong.”

When Jan Ramsey and I lived on Second Street, just about a block from Dryades Street, the traditional intersection where Black Masking Indians meet on Mardi Gras day, Sinclair was always present. He would frequently come over for food and drinks. But my relationship goes back to before I was working with Jan at OffBeat. I was managing bands and placed advertisements in OffBeat promoting the bands, when I first met John Sinclair. You had to pass Sinclair’s office to get to Ramsey’s office. It was at this time, 1995 or thereabouts, that Sinclair and the OffBeat staff organized the Crescent City Blues Club. They asked me to help manage and organize a Crescent City Blues Club concert. I had become friends with Jimmy Anselmo and asked him to host the event. John Sinclair and His Blues Scholars were the headline band and it was at this event that Anselmo met his current wife.

A True Hippie

Born in Flint, Michigan in 1941, Sinclair’s father worked for Buick and his mother was a high school teacher. Sinclair grew up in Davison, close to Flint, and graduated from the University of Michigan-Flint in 1964 with a degree in English literature.

Fred Goodman, in his book The Mansion on the Hill describes Sinclair childhood. “As a kid he hung around black barbershops and pool halls, and he developed a passion for avant-garde jazz. Though white, he felt an affinity with the emerging black nationalist philosophies of Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad. Sinclair was a true ‘hippie,’ that slang expression for a white person who wanted to be part of the black scene because it was “hip.” Sinclair said “I spent two or there years being part of a black community up in Flint because that was the only place where there were people like me… like the person I wanted to be. There weren’t any white people like that.”

By the mid-1960s he was an emerging young poet.

During his time at UM-Flint he served on the university’s publications board, school newspaper The Word, and was the president of the Cinema Guild. Sinclair was music editor and columnist for the Detroit underground newspaper, Fifth Estate, during the paper’s growth in the late 1960s. Sinclair also contributed to the formation of Detroit Artists Workshop Press, which published five issues of Work Magazine. Sinclair worked as a jazz writer for Down Beat from 1964 to 1965, being an outspoken advocate for the newly emerging Free Jazz Avant Garde movement. Sinclair was one of the “New Poets” who read at the seminal Berkeley Poetry Conference in July 1965.

In April 1967 he founded the Ann Arbor Sun, a biweekly underground newspaper, with his wife Leni Sinclair and artist Gary Grimshaw.

John Sinclair when he was manager of MC5

MC5

Sinclair often kept a toehold in the world of music, managing for a time Mitch Ryder and MC5, a hard-rocking forerunner to the punk movement.

But it was his role as manager for the Detroit rock band MC5 that brought Sinclair world-wide attention. In 1968, Sinclair became a founding member of the White Panther Party, a militantly anti-racist socialist group and counterpart of the Black Panthers. In Guitar World, Sinclair described “the crazed guerilla warfare we were waging with the MC5.”

The MC5’s first album caused some controversy due to John Sinclair’s inflammatory liner notes and the title track’s rallying cry of “Kick out the jams, motherfuckers!”

Goodman wrote in The Mansion on the Hill that Sinclair underestimated both rock and roll and the MC5. “You could see that something big was happening,” he says. “Rock and roll was growing and it was going to include jazz and it was going to include blues and all the interesting things from the past.”

Marijuana and Immortality

Fred Goodman wrote that “Sinclair… was a proselytizer for marijuana, which he referred to as ‘the sacrament.’ Along with actively lobbying to have it legalized, Sinclair was well-known around Wayne State as the person to see if you wanted a couple of joints.”

In 1965, an undercover narcotics officer purchased marijuana from Sinclair, for which he served six months in jail.

Arrested again for possession of marijuana in 1969, Sinclair was given 10 years in prison, by Judge Robert Colombo, applying the maximum sentence more than likely because Sinclair was also a co-founder of the White Panther Party. The sentence was criticized by many as unduly harsh, and it galvanized a noisy protest movement led by prominent figures of the 1960s counterculture. Sinclair served 29 months but was released a few days after John Lennon, Stevie Wonder, Bob Seger and others performed in front of 15,000 attendees at the University of Michigan’s Crisler Arena. In the song “John Sinclair” by John Lennon, he sings “They gave him 10 for two/ What else can Judge Colombo do/ We gotta set him free.” This basically immortalized Sinclair.

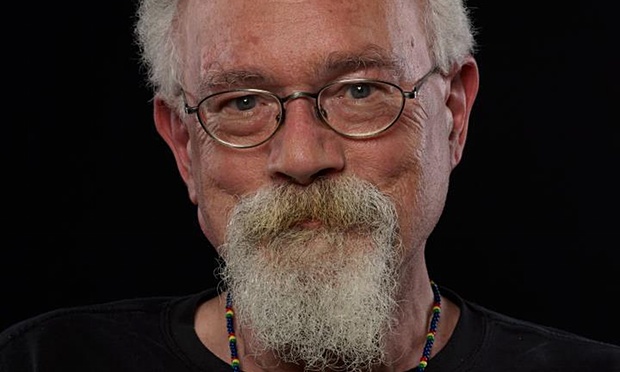

Photo courtesy of Iron Man Records.

During his time in prison MC5 dropped him as manager. Bitter, Sinclair wrote: “You guys wanted to be bigger than the Beatles, I wanted you to be bigger than Chairman Mao.”

Sinclair never stopped promoting—and partaking in—the use of marijuana. He helped create Hash Bash, a yearly pot celebration at the University of Michigan, and served as state coordinator of the Michigan chapter of NORML, the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. “The only issue I’ve really kept active on is marijuana, because it’s so important,” he told the Free Press. “It’s been a continuous war for 80 years on people like you and me. They’ve got no business messing with us for getting high.”

When the White Panther Party was dissolved in 1971, Sinclair formed the Rainbow People’s Party, which embraced and promoted the revolutionary struggle for a “communal, classless, anti-imperialist, anti-racist, and anti-sexist, culture of liberation.” Sinclair said in 2013: “In those times, we considered ourselves revolutionaries… We wanted equal distribution of wealth. We didn’t want one percent of the rich running everything. Of course, we lost.”

New Orleans

Fred Goodman writes that after his divorce from his first wife Leni, ‘he moved in the late eighties to New Orleans, where that city’s rich African American music heritage could nurture a middle-aged Beat poet.”

After moving to New Orleans, Sinclair started writing for Wavelength Magazine and for OffBeat Magazine. He subsequently became involved at community radio station WWOZ, hosting “The New Orleans Music Show” on Wednesdays.

In New Orleans, Sinclair performed and recorded his spoken word pieces with his band The Blues Scholars, which included such musicians as Wayne Kramer, Brock Avery, Charles Moore, Doug Lunn, and Paul Ill, among many others.

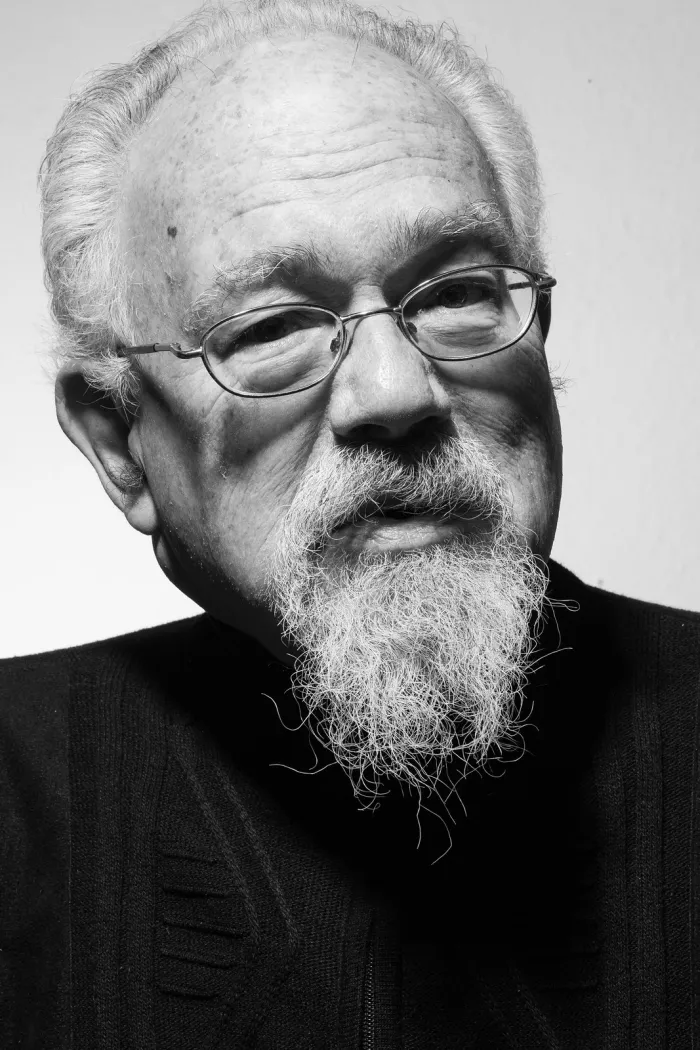

Joseph Irrera and John Sinclair, Mardi Gras Day 2010 at Second and Dryades Street. Photo by Anitra Irrera.

John Swenson wrote in OffBeat: “Sinclair’s stint as a DJ on WWOZ helped codify what we know of the history of the Mardi Gras Indians. Many of the Indian gang members listened to and studied his broadcasts to help understand their own tradition. As a poet and storytelling bard, Sinclair employed various groups of local musicians in what he called the Blues Scholars to improvise music behind his elaborate tales about the legends and myths of blues and jazz greats from the past, from John Coltrane to Big Chief Bo Dollis, from Robert Johnson to R.L. Burnside.”

“Even though he is an expatriate, John Sinclair should be declared a national treasure” wrote David Kunian in OffBeat. “He’s a poet, historian and musicologist who, instead of publishing his research and findings, declaims them in the oral tradition with music.”

During his time in New Orleans Sinclair left an indelible impression on the city though his work as a journalist, historian, poet, performance artist and radio host.

Amsterdam

He left New Orleans for Amsterdam in 2003.

A year later in 2004 Sinclair created the John Sinclair Foundation, a non-profit organization to ensure the preservation and proper presentation of his creative works via poetry, music, performance, journalism, editing and publishing, broadcast and record production.

In 2006, Sinclair joined The Black Crowes on stage at the Paradiso in Amsterdam and read his poem “Monk in Orbit” during the instrumental break in the song “Nonfiction.” Two days later, he went back onstage at the Black Crowes show in the Paradiso, reading his poem “Fat Boy” during the long instrumental jam following the Black Crowes’ song, “How Much for Your Wings?”

On January 20, 2009, to mark Barack Obama’s inauguration as the 44th President of the United States, Sinclair performed a series of his poems accompanied by a live band, featuring Elliott Levin, Tony Bianco and Jair-Rohm Parker Wells at Cafe OTO in Dalston, East London.

In 2011, Sinclair recorded spoken word for the intro to the song “Best Lasts Forever” by Scottish band The View, produced by Youth.

The Next Revolution

John Swenson wrote in OffBeat: “The itinerant Sinclair now spends his time traveling, mostly between New Orleans, Detroit and Amsterdam. His bohemian lifestyle is poignantly described in one of the poems from this collection: ‘everything happens to me’: ‘a man without a country & a post office box in New Orleans for a permanent address, a pre-pay vodaphone & a laptop computer, one suitcase stuffed with clothing & a bag full of manuscripts & hand-burnt CDs—to keep my head straight & my heart right to keep up my travels & carry on the struggle into another new year, taking my little verses & a great big world outlook everywhere people will have me.”

Sinclair had two daughters from his marriage to Leni Sinclair. They divorced in 1988. In 1989, Sinclair married Patricia Brown.

Talking about the next revolution Sinclair says: “next time the revolution comes, I’m gonna duck.”

Tributes Posted On Facebook

Today we lost a great American with the passing of John Sinclair. I first met John when I was a 24-year-old poet and cook at the Clover Grill and he was a 54-year-old poet and patron of that insane 24-hour gay Bourbon Street diner. I had no idea that he was already a legend, that John Lennon had written a song about him, that he had organized the White Panther Party, started the Rainbow family, managed the MC5. I just thought he was cool. We bonded over Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Howlin’ Wolf and John Coltrane. He dedicated Santo and Johnny’s “Sleepwalk” to me from his WWOZ radio show (called me the greatest grill cook in the world). We became friends, and he became a mentor. He introduced me to Sun Ra and Ed Sanders and Mardi Gras Indian music. He took me to Indian practice at Snake’s Players Club. I shared the poetry stage with him a few times, and I thought I had really “made it.” I mean this was a guy that was booked with folks like David Amram and Amiri Baraka. I even booked his very first gig in Mississippi. He taught me a new way of moving through the world. He gave me friendship and built my confidence at a really crucial time in my development as a human. He was truly one of the most impactful folks in my life. Rest well, John. Thanks for all the words and for the love.

“(god give us strength to be tender & unafraid / to sing, sweeter voices rising above their screams. or dance / create a grace among these clumsy corpses / stumbling against our shins.”—from This is Our Music by John Sinclair, 1965.

—Bradley Sumrall

They say it comes in 3’s. Well, this is my third friend to pass in a week. What an extraordinary life John Sinclair led. Poet laureate, blues scholar and aficionado, radio legend and perhaps America’s most important and esteemed cannabis activist. I had many deep, interesting and enlightening conversations with him over the years. He was gracious but did not suffer fools.

My brother threw a festival in the early 2000’s and we hired John to be the emcee. My old band, Juice, played two sets at the fest: a night show of our music and the following day we kicked off the fest by doing a groove/jam improv set, backing up John as he recited and improv’d his poetry. I think some of it was from his album “Fattening Frogs For Snakes.” At the time I thought the recording was kind of terrible (I hate listening back to my stuff), but I stumbled across it years later and took another listen and it was actually pretty cool. I might have to track it down today. I’m sure it’s in a pile somewhere.

Fly high, old friend, no doubt you will. Send me some poetic inspiration sometime. I’ll keep my radar up.

—Dave Jordan

RIP brother John boy we had some times, sad day.

—Carlo Ditta

John Sinclair was the first DJ to play a song of mine on WWOZ it was 2000, John Boutté brought me to the old studio in Armstrong Park, we ride our bikes from his place in the Treme, Boutte’ asked John to play the song.

I offered to smoke a joint with him in the park while it played but John just smiled and said, “Let’s have a smile while we listen.” He played “Foot Of Canal Street,” the three of us “listened,” and I enjoyed one of my favorite ever New Orleans moments.

“Say a prayer for John Sinclair.”

—Paul Sanchez

My thirtieth birthday present from John Sinclair. Always delighted and honored to be able to call John both friend and colleague. Tonight, those little white puffs in the heavens aren’t clouds.

—Michael Tisserand

Very saddened to hear of the passing of my friend John Sinclair. I have so many fond memories of hours of insightful conversations with him over the years. “…John, what was it like knowing J Edgar Hoover & Richard Nixon hated your guts?…” “…John, why do you think you’ve never been asked to judge the Cannabis Cup in Amsterdam?…” A few years later, when the powers that be acknowledged their oversight & named him a judge: “…John, what criteria do you use when you judge entries, & what was a favorite entry you sampled at the last competition (I recall he was a fan of White Widow)…” Thank you for your friendship. Be well. Enjoy that Celestial Celebration we talked about, & give Edsel a hug.

—Michael Garran

Such a wonderful person, and I’m so proud he played my club Jimmy’s. I’m honored that he did, and we were good friends.

—Jimmy Anselmo

Sinclair was brilliant, brave and absolutely one of a kind. When we lived on Second Street, we’d always run into him (after he left NOLA for Amsterdam) at Dryades during Mardi Gras and hang with him and the Indians. Much better there than at Second and St. Charles. RIP, John.

—Jan Ramsey