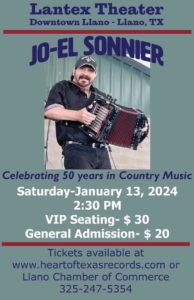

Grammy Award-winning Cajun and country artist Jo-El Sonnier passed away at the age of 77. Sonnier suffered a fatal heart attack following a performance in Llano, Texas on January 13, 2024.

Sonnier had completed the show at the Llano Country Opry and according to music promoter Tracy Pitcox: “Sonnier ended his performance with ‘Tear-Stained Letter,’ and received a standing ovation. He agreed to perform ‘Jambalaya’ as an encore. He performed energetically and then mentioned he needed to rest before signing autographs. Sadly, he suffered cardiac arrest and was airlifted to Austin, where he was pronounced dead.”

Jo-El Sonnier was born to French-speaking sharecroppers in Rayne, Louisiana on October 2, 1946. At age three, he began to play his brother’s accordion. By age six, Sonnier had performed on the radio; at age 11, he made his first recordings, including writing his first song “Tes Yeux Bleu,” now considered a classic. He also released several independent singles and four albums as a teenager. By the 1970s, he was signed to Mercury Nashville Records, but did not have much success in the country music field.

Sonnier temporarily abandoned his pursuit of a country music career in favor of recording Cajun music on the independent label Rounder Records. Although his independent album Cajun Life did not produce much commercial success, it was nominated for a Grammy Award. After being signed as Merle Haggard’s opening act, Sonnier later decided to return to country music. He signed with RCA Records in the 1980s, where his biggest successes came in the singles “No More One More Time” and a cover of British singer Richard Thompson’s “Tear-Stained Letter,” songs which landed in the top ten on the country charts.

In the 1990s, Sonnier moved to Capitol Records, but his solo career faltered soon afterwards. He continued to find success as a session musician, and briefly took up acting as well. Sonnier made a brief cameo appearance as a member of a dance band in the third episode of the first season of the HBO crime series True Detective.

In the late 1990s, he returned to Rounder Records to record Cajun music once more, occasionally collaborating with Michael Doucet of BeauSoleil. Sonnier also saw his second Grammy nomination, for the 1997 album Cajun Pride; a third soon followed with 2001s Cajun Blood that was nominated for Best Traditional Folk Album.

In the July 2022 issue of OffBeat, Dan Willging wrote:

The son of poor, French-speaking sharecroppers, Cajun-country musician Jo-El Sonnier has been a survivor his entire life. Hurricanes Laura and Delta ravaged Sonnier’s Westlake home. “It was not livable. Everything was destroyed,” Sonnier described. “The hurricane completely took the house apart with all the wind and debris.” Sonnier and his wife Bobbye moved from one friend’s house to another friend’s house. It would be 18 months before they could move back into their comfy A-frame home.

In the July 2020 issue of OffBeat Herman Fuselier talked more about the hurricane’s devastating consequences:

“Jo-El Sonnier knew the 4:30 a.m. phone call in late August couldn’t be good news. A friend told the Cajun and country music icon to pack what he could and get out. Hurricane Laura, lurking in the Gulf of Mexico, had grown into a major storm with 150-mph winds. Laura’s impact would be “unsurvivable” in parts of southwest Louisiana, the National Weather Service said.

Sonnier and his wife Bobbye drove five hours north to Winnsboro, Texas, where they stayed for five days. On the drive back to their Westlake home, the Sonniers felt angst that grew with each mile.

“Around Orange, Texas, we started seeing all the trees down and homes smashed in,” said Sonnier, 73, a Grammy winner in 2015. “By the time we got to Vinton, it was even worse. In Sulphur, our friends had huge trees on their roof. It was devastating to see their home.

“We couldn’t get to our house because [the road] was all blocked up with trees. Our house is very, very damaged. It’ll be at least a year before I can get back into it.”

Dan Willging continued:

To get through it all, Sonnier said he “stayed in communication with the good Lord and in some way, He managed to hear our prayers.” About the time the Sonniers were about to move to Texas, a guardian angel of sorts appeared in the form of Robert Monceaux. He had just stopped by to buy a piece of antique furniture the Sonniers were selling. As luck would have it, Monceaux was a licensed contractor and took the reins to get the Sonniers’ house put back together, overcoming the challenges of delays, worker shortages, and rising labor and material costs.

As unsettling and trying, as a situation like this would be to anyone, it was especially challenging for Sonnier, who has Asperger’s syndrome, a form of autism that depends on the structure of a daily routine. “[Autistic people] don’t do change very well,” says Dr. Shirley Strange-Allen, Sonnier’s sister-in-law and specialist in working with autistic children. “Jo-El almost went into a depression because his routine was so disrupted.”

Jo-El Sonnier, photo by Jesse Hitefield.

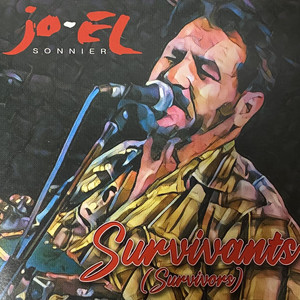

To get some relief from reality, Sonnier plunged into his music and began writing songs at a prolific pace that would eventually become his 35th album titled Survivants (Survivors). “All those songs on the album were not, ‘oh yeah, I think I’m going to write a song,”’ Sonnier said. “The only way to release what I was feeling was to start writing my songs, and that’s how this album came about.”

With Monceaux serving as executive producer and Tony Daigle as engineer, Sonnier recorded and produced Survivant at Dockside Studio. He was backed by his regular squadron of top-flight musicians: Kevin Hare, bass; guitarist Ray Ellender, guitars; Ellender’s son, Ty, drums; and Jess Yates, pianist/synthesizer. Joe Rogers played steel guitar. In the fiddle department, Sonnier enlisted four of Acadiana’s best, Michael Doucet, Joel Savoy, Terry Huval and his son Luke.

Since the coronavirus was raging then, Sonnier could not rehearse the entire group at one time, so he worked with the musicians in smaller groups. Terry and Luke Huval found the experience of working with Sonnier quite enchanting. “He’s very visionary in the sense that he can imagine a lot of parts going on, whether it’s vocals, fiddle, guitar, accordion, fiddle, drums,” Luke explained. “He has a vision of what he wants the songs to sound like. It was really a process of making it all come to life.”

Terry echoed his son’s sentiments and described Sonnier as “very passionate. He has a lot of passion in his heart, and he tries every way he can to really put it out there, so it works out in the songs,” Terry says. “It’s a mixture of lines that he will write. He’ll have an idea of what kind of melody he wants to go with and then just let his thoughts go the way they want to go. It’s a very interesting process watching him do that.”

Luke and Terry played twins on “Mon coeur fait mal,” and Luke single-handedly drove the ferocious lead on the opening firecracker track “Chers yeux noirs.” Luke also teamed up with Joel Savoy on several others for some soulfully penetrating harmonies.

A dozen days later, Sonnier wrapped up the recording aspect of the project. Sonnier wrote every song on Survivants, with the title track being co-written with longtime collaborator Nashville songwriter Billy Henderson. The album features two moving versions of “Survivants,” an all-French one and a mostly English one with some French as a bonus track. “Quand mon temps vient” (“When My Time Comes”), was dedicated to the memory of his brother P.J. with the realization that despite his abundant energy—remarkable for a man of 75—life is finite.

In the liner notes, Sonnier profusely thanked many people instrumental to the project or who played a role in his life, including his sister-in-law. To her, he writes, “To my sister-in-law Shirley Strange-Allen, for helping me to understand that being autistic is what gives me my ability to do what I do, and it’s not just a disability. I can still do what most normal people do, I just do it in a different way, and that’s okay.”

Jo-El Sonnier and sister-in-law Shirley Strange-Allen with the book The Little Boy Under the Wagon. Photo by David Simpson.

Strange-Allen found her brother-in-law’s story so compelling that she had to write about it in her children’s book The Little Boy Under the Wagon. “I thought people needed to understand why he is like he is and where he was coming from and how far he has come, despite all the obstacles placed in front of him,” Strange-Allen explained. “I mean, unbelievable obstacles, because of the time and his parents being sharecroppers. It was a very difficult time to raise children, much less one that was different.”

“Most autistic people are very artistic and very intelligent, maybe not in schoolbooks but in other [ways],” Sonnier says candidly. “Mine is in my music, and that’s what saved me. I don’t think it’s a handicap. It’s just part of birth, and I use that to help others.”

Early on, Sonnier’s parents noticed their three-year-old’s restless energy and put an accordion in his lap to occupy him. He not only learned to play it but master it. “With music, he helped support his family when he was between four and five years old because he would play in between cock fights,” Strange-Allen explains. “They would sit him in the pit, and he would play his accordion, and they’d throw pennies and nickels, and that’s how he made money for his family.”

Strange-Allen says that’s one of the stories in the book. From there, Sonnier started playing with adult bands. Along the way, Aldon Sonnier, a disk jockey at Crowley’s KSIG radio station, noticed the budding prodigy and offered him a 30-minute radio show. Sonnier’s father took him to the radio station for his daily early morning show, then dropped him off at school after grabbing a donut or two.

Sonnier often played his accordion underneath an old wagon (the impetus for the title of Strange-Allen’s book) while his father and the rest toiled in the cotton fields.

At age 11, Sonnier put his first band together, The Duson Playboys, and headed to Ville Platte to record at Floyd Soileau’s studio. Initially, they recorded only one song, “Duson Playboys Special,” not knowing that two songs were needed to complete a 45. “When we were packing up, he came out of the studio and asked me what we were doing,” Sonnier recalls. “He said, ‘You boys can’t leave right now because we have to have another song.’ I had this song in my head with the words.” Consequently, Sonnier and his band recorded one of the all-time Cajun classics, “Tee Yeaux Bleu.” Sonnier goes on to say the record was released when he was 13.

“Mr. Floyd said I was the first minor to record,” Sonnier recalls. “I was a trailblazer.”

In 1959, a 13-year-old Sonnier won an accordion contest at the Crowley Rice Festival and shook the hand of Senator John F. Kennedy, who was visiting South Louisiana with his wife, Jackie.

Sometime in the early ’70s, Sonnier and a group of Cajun musicians were invited to play at the San Diego Folk Festival. The experience of playing Cajun music to an appreciative audience outside the Pelican State was so moving that it sent Sonnier in a whole different direction. “Something told me right then that I needed to carry the banner because we had lost so many of our unsung heroes like Iry LeJeune and Lawrence Walker,” Sonnier said. “It made me realize this is what my mission is about.”

Jo El Sonnier at the Grammys. Photo from Twitter (X).

For a while, Sonnier served as a sideman in various bands around Southern California. In Phoenix, Sonnier met Earle Poole Ball (before he was Johnny Cash’s pianist), an independent Nashville producer, head of Earl Ball Productions, and his publishing company Wall to Wall Music. Ball asked Sonnier if he wanted to write songs. “Well, I’ll do what I can,” Sonnier remembers telling Ball. “He said, ‘I love your singing and you need to come down to Nashville and be recorded.” So, off Sonnier went to Nashville, recorded a demo at Peter Drake’s studio, and Ball pitched it to Mercury Records, who signed him.

With that, Sonnier became one of the few Cajun artists who combined their Cajun heritage with Nashville country, joining the ranks of Jimmy C. Newman, Doug Kershaw and Eddy Raven. While Newman and Raven played guitar and Kershaw a dizzying, high-octane fiddle, Sonnier is probably the first Cajun artist who came to Nashville with the accordion being his primary instrument.

Of Sonnier’s ’70s Mercury output, “I’ve Been Around Enough to Know” peaked at number 78 on the Billboard country singles chart, a rendition of Lefty Frizzell’s “Always Late” and “He’s Still All Over You” each spent a week scraping the bottom edge of the top 100. Ironically, his last Mercury single was the autobiographical “Cajun Born” before the label dropped him, as eventually did Ball. As a parting gift, Ball introduced Sonnier to film director Peter Bogdanovich where both Ball and Sonnier had roles in the romantic comedy They All Laughed.

Doors began to open for Sonnier again when Johnny Cash recorded “Cajun Born” for his 1978 Gone Girl LP. Cash’s introductory words “Play It pretty, Jo-El” remain one of Sonnier’s most cherished memories. Since then, “Cajun Born” has been recorded by Newman and Emmylou Harris.

For several years there, Sonnier was asked to play on recordings by such high-profile artists as Merle Haggard (“Sky-Bo”), Mark Knopfler (“Cannibals“), Alan Jackson (“Tall Tall Trees”), Elvis Costello (“American Without Tears”) and the list goes on, too numerous to cite unless it’s a Sonnier autobiography. He even played on Dolly Parton’s number one chart-topping hit “Why’d You Come in Here Lookin’ Like That” that was a part of her ’89 album White Limozeen.

One request that was initially baffling to Sonnier was when Hank Williams Jr.’s people asked him if he could play a concertina on “Norwegian Wood,” a Beatles’ milestone song. “I didn’t even know what the word concertina meant,” Sonnier admitted. Instead, he told them he played “a French Cajun Mamou Air Compressor. I made a joke out of it. That’s what my attitude was in those days, real hardcore Cajun.”

One request that was initially baffling to Sonnier was when Hank Williams Jr.’s people asked him if he could play a concertina on “Norwegian Wood,” a Beatles’ milestone song. “I didn’t even know what the word concertina meant,” Sonnier admitted. Instead, he told them he played “a French Cajun Mamou Air Compressor. I made a joke out of it. That’s what my attitude was in those days, real hardcore Cajun.”

“I mean, all those different artists were so warm, and kind and they said ‘Man, we want this sound on our records,’” Sonnier said. “And that’s how I got to play on so many different records.”

If you want to cite those that have practically done it all, Sonnier would have to be included on that list. He opened up for Merle Hagggard on a tour, and shared the stage with Alabama, Charlie Daniels and Lee Greenwood, among others. In the 1980s, he signed with RCA Records and had Top 10 hits with “No More One More Time” and a rollicking rendition of Richard Thompson’s “Tear-Stained Letter.”

Besides acting in They All Laughed, Sonnier had subsequent roles in his friend Peter Bogdanovich’s movie Mask, starring Cher, where he played a biker dude named Sunshine. He played himself in The Thing Called Love, another Bogdanovich flick, in 1993.

Along the way, he was Grammy-nominated five times for his traditional Cajun albums and finally took home the gold in 2015 for his album The Legacy. It seems that the only thing Sonnier hadn’t done by then was to play his accordion while skydiving from an airplane.

Terry Huval felt Sonnier could have had another Grammy nomination on his hands with Survivants. Though months had passed since Huval and his son Luke contributed to Survivants, the senior Huval was even more impressed with its beauty and sentiment. He writes in a message: “I’m hearing so much raw passion in those songs and arrangements. You can feel the weight of the hurricane devastation in every word. That man really has a gift.”

Things slowly got back to normal for Sonnier when his house was put back together, and the bookings rolled in. In May, he and his crew played at a Vicksburg, Mississippi casino, where he caught up with his old friend, actor Judge Reinhold, whom he first met at the Palomino Club in Los Angeles. Reinhold also wrote the script for Sonnier’s “Tear-Stained Letter” and acted in the video. In between live shots of Sonnier and a live band, Reinhold has a bad dream about being tossed around the room by a woman who’s supposed to be his better half.

On July 2, Sonnier played the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville for what he estimated would be his tenth or twelfth time and his first in five years. “I’m real excited about that,” Sonnier said. “It will give me an opportunity again to play the music of my roots.”

A career that spanned 35 albums; five Grammy nominations and one Grammy Award; and gigs in all 50 states and 32 countries, was a remarkable run for Sonnier, who said he had been in the music business for 67 years. “That’s a long time to be in this game,” he said. But you can bet that the game wasn’t even close to being over for Sonnier who had plenty more innings left to play. After all, he was a survivor.

As a songwriter, Sonnier had his songs recorded by Johnny Cash, George Strait, EmmyLou Harris, John Anderson and Jerry Lee Lewis.

In 2008, Jo-El Sonnier was named to the Cajun French Music Association Hall of Fame and in 2009, Sonnier was inducted into The Louisiana Music Hall of Fame. In 2015, Sonnier won a Grammy Award for The Legacy, the Best Regional Roots Music Album. In 2021 Survivants received OffBeat’s Best of The Beat nomination for Best Cajun Album.

Jo-El Sonnier is survived by his wife Bobbye, the person he considered to be his soulmate.

Photo by David Simpson.

Tributes include from Twitter or X include the following:

Saddened by the loss of dear friend Jo-El Sonnier, Cajun legend. Rest in peace, long-time friend.

—Joe Bonsall, The Oak Ridge Boys

Heartbroken to hear the news about the passing of our friend Jo-El Sonnier, there are not enough kind words to describe him. Rest in peace, buddy.

—Bellamy Brothers

The Charlie Daniels family was sad to learn about the passing of Grammy-winning Cajun accordion virtuoso, Jo-El Sonnier. Jo-El crossed paths with and sat in with the CDB on many occasions and Dad thought a lot of him. Rest in peace Jo-El. Heaven must’ve needed a squeezebox player.

—Charlie Daniels, Jr.

RIP, you life-loving, music-loving legend, you. I will miss you reaching out to me for the Westlake gossip. You brought joy to so many and went out as we all knew you would—entertaining.

—Brandy LaFleur

Today, Sheila and I lost one of our very best friends. Jo-El Sonnier. Cajun music trailblazer and a wonderful man, he will be missed by all. Please pray for his wife, Bobbye. Adieu, my dear friend.

—T. Graham Brown

The Festivals Acadiens et Créoles website profile of Jo-El Sonnier ends with this quote: “I perform every show as if it was my last, and it doesn‘t matter to me if there are only 25 people or 25,000 people in the audience, I still perform the same way.”