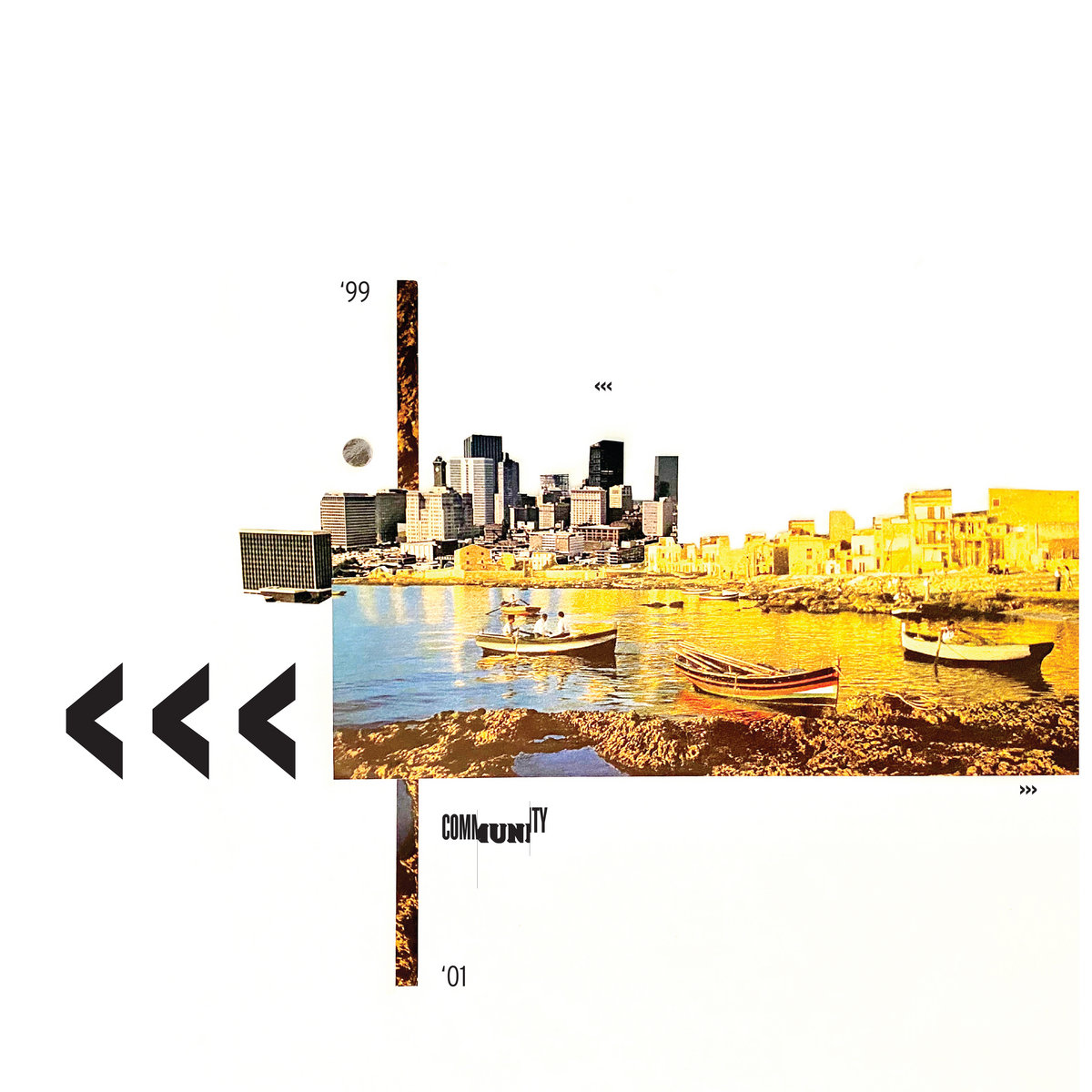

What started as an archival project of a college student grew into the reunion of two Westbank bands: Community, an indie rock band active between 1999 and 2001, and Fatter Than Albert (FTA), a ska band who broke up nearly 12 years ago. Nearly 400 people showed up for the 250-cap venue.

Rob Landry of the band Mesopeak, who also performed that night, told the audience it was like playing for three generations of do-it-yourself (DIY) rock in the same building.

“They were the class ahead of us,” said Greg Rodrigue of Fatter Than Albert, “[Community] were seniors when we were freshmen, so we looked up to them.”

A few years younger, Landry and the members of Mesopeak saw FTA as their graduating class. Three mini-generations, hundreds of people, all on a Wednesday between Christmas and New Year’s, gathered to celebrate the aptly named band that inspired it all: Community.

Kevin Comarda bassist and vocalist in Community at the album release show December 28. Photo by Dalton Spangler.

Coming up in the middle and late ‘90s, a boom of alternative rock music surrounded the members of Community. Southeastern Louisiana sludge metal like EYEHATEGOD and Acid Bath were establishing a unique scene at the time. On the opposite end of the spectrum, bands like Rigid were fighting misconceptions of being labeled a metal band, making heavy music for “nerds.” Beyond the underground, the former LSU college students Better Than Ezra were topping charts and getting national airplay with their brand of pop rock.

“There were cool bands but it wasn’t a music scene,” said Kirk Estopinal, guitarist and vocalist in Community, “I think the punk scene kind of grew with us.” Estopinal recalled Deborah Toscano of Devil Dolls booking shows and Underground Sounds, a record store on Magazine Street, creating a retail space for the music.

“But the Faubourg Center is what really made the scene,” he said.

Located at 508 Frenchmen Street where The Maison is now, the Faubourg Center would rent out space to French Market vendors during the day and punk bands at night. They would see legacy bands there like Guttermouth, The Bouncing Soul, A.F.I. and others.

“There was a time when you’d go down on a Friday or Saturday and there’d be a bunch of kids drinking 40s and smoking cheap cigarettes,” Estopinal recalled, “And then you’d go see the punk show. I went there hundreds of times. I met my wife there.”

In those days, the members of Community were a part of a separate band called The Supaflies, one of the most well-known ska bands to come out of New Orleans at this time. While still in high school and attending shows at the Faubourg Center and other places, the Westbank band began mimicking the touring bands visiting their city and crashing on their couches. They quickly learned how to be booked for shows and pick up tours with Less Than Jake, Suicide Machines and Voodoo Glow Skulls.

Kirk Estopinal, guitarist and vocalist in Community at the album release show, December 28. Photo by Dalton Spangler.

While touring other cities, the band would see how independent music scenes operated, sowing the seeds that would eventually grow into a part of the NOLA DIY community and the unironically named band, Community.

“Then after high school, once everyone started going to college, we decided to do the horn parts vocally,” said drummer and vocalist Ryan Iriarte about the progression from The Supaflies to Community, “We played so much that we actually started sounding good.”

The final four members of The Supaflies formed Community. The unofficial fifth member of the band, Chris George, owner of The Living Room Studio, helped them record their album within his home studio in Gretna.

“It was the original living room studio,” said Kevin Comarda, bassist and vocalist in the band, “and now everybody has a home studio.”

“He cut a hole in the wall in teh front bedroom so he could see between the two rooms,” said Estopinal.

“We were watching TV, just hanging out and drinking and then Chris comes out says, ‘You know what, fuck it,’ and starts hitting the wall with a hammer before getting a Sawzall to cut the whole thing,” Iriarte continued.

“I lived there and I had drywall in my pockets for six months. It was everywhere,” said Travis Thompson, guitarist and vocalist, “You’re breathing all this drywall from the 1950s and he’d say, ‘Don’t worry about it man, now we have a drum room.’”

Beyond DIY home renovations and recording the band’s record, George replaced the engine and transmission of their first touring van.

The house became their regular hang-out and base of operations, burning the CD-Rs that took 30 minutes a copy that would later be given away and enjoyed long after the band broke up.

“We had no idea of this afterlife,” Comarda said about the album.

The friend group slowly dissolved due to a variety of reasons. People stopped playing altogether, new bands formed and Hurricane Katrina happened leading to the project being almost forgotten if it weren’t for a few inspired locals.

Eric Rodgers, who played percussion on stage with the band at their reunion show, was a few years younger than Community and grew up in Ninth Ward, but still discovered the album.

“My brother and his friends were fans and would go to shows,” Rodgers explained, “Somehow, I ended up with a burned CD in my ‘95 Ranger and it actually got stuck in the CD Player so all I could listen to was that CD.”

The album inspired him and many of his friends when they started their band, Antenna Inn.

“We wanted to record [an album] and where do you go? There’s only one place you go and that’s where Community went,” Rodgers said about their decision to record with George.

Saxophonist and vocalist of FTA Charlie McInnis performing at the Community album release show, December 28. Photo by Dalton Spangler.

Around that same time, the future saxophonist and vocalist of FTA Charlie McInnis, gave away copies to his friends, including Rodrigue and the people who would eventually make up FTA and other projects.

“The album was in constant rotation in the van when FTA was on tour,” explained Rodrigue.

Being a ska band that grew up in the same neighborhoods as Community, making music seemed more attainable to Rodrigue and FTA. Community paved a path for Rodrigue and Daniel “D-Ray” Ray to start Community Records, named in part to honor the band.

“It represented what we wanted to do with the label and also the band that was so influential to us,” Rodrigue said.

Rodrigue and FTA would get the opportunity to share a bill with the band when they announced they’d perform the day before the Community album release show at Siberia. Three members had to fly in from out of state to perform. Yet, even with minimal promotion, much of the crowd that attended came for the ska band.

The turnout testifies to how much FTA and Community Records has also done to continue the DIY music legacy that started with the Westbank crashpad studio. Community’s influence on the label’s founders inspired them to co-release the project with another DIY music label Strange Daisy Records.

Founded by Patrick Bailey, who also plays guitar in Mesopeak, Strange Daisy Records formed in 2016 to provide a platform for a growing generation of New Orleans indie rock. One of the first records Bailey wanted to see on vinyl was the Community album.

“I really wanted to hear the music on vinyl and if I could only make one, I’d want to make this record,” said Bailey.

He discovered the record the same way FTA did, through McInnis. Blown away by the guitars, technical skill, songwriting and psychedelic style recording, the album left a lasting influence on the young Bailey. In college, he began an archival blog project called The Memory Farm to document local music.

Nearly 15 years later, he still had the original copy stored digitally on the website and began pitching the idea casually to members of Community. Once he had Community Records onboard, he could easily make a deal with the former members.

At this point, Community [the band] had split, gone their separate ways and returned to the Westbank to work and start families. Estopinal runs the restaurant Cane & Table in the French Quarter, Iriarte is a lead bartender at Bearcat Cafe in the CBD, Thompson runs his own honey and apiary called Raw Honey New Orleans while Comarda works as a visual artist and musician playing in a few local bands including The Self-Help Tapes and The Fruit Machines.

Once the two labels approached the band, the grown-up members decided to step back into their younger selves and relearn the music for the show that would accompany the release.

“It’s like the end of the kid part of us and the beginning of where we go from here,” Iriarte said about the experience and their plans moving forward.

The release serves as an archival piece capturing a unique moment in New Orleans’ music past while creating a new moment in the present. The remastered Community album is available now on vinyl and streaming platforms.