Singer and songwriter, Clarence “Frogman” Henry passed away, after years of declining health, on Sunday, April 7, 2024. He was 87.

Clarence “Frogman” Henry on the 2006 OffBeat Jazz Fest Bible.

Frogman’s song “Ain’t Got No Home” was the inspiration for OffBeat Magazine’s Jazz Fest Bible cover in 2006, as it reflected the situation for so many New Orleanians after Hurricane Katrina and the failure of the levees devastated the city.

Henry was born in New Orleans’ Seventh Ward on March 19, 1937. In 1948 his family moved to the Algiers neighborhood.

He started taking piano lessons as a teenager, with Fats Domino and Professor Longhair as his influences. At 15-years-old, he bought his first piano for $610 from Hall Piano in Metairie. In 1952, while still in high school, Henry joined Bobby Mitchell & the Toppers, playing both trombone and piano. After Henry graduated in 1955, he joined Eddie Smith & His Chiefs.

Piano Lessons

In the March 1996 issue of OffBeat, Rick Coleman interviewed Henry:

At age six, Clarence talked his mother into taking the piano lessons that his sister shunned. “She wanted me to play classical music and when she would leave to go to work, I would get there [on the piano] and play boogie.”

Little Clarence’s boredom with the long-haired stuff seemed to be justified when, in the sixth grade, he shut down the school’s little girl virtuoso with his black-and-red checked jacket and some lowdown boogie: “I was playing Professor Longhair and Fats Domino, and the kids just went wild.”

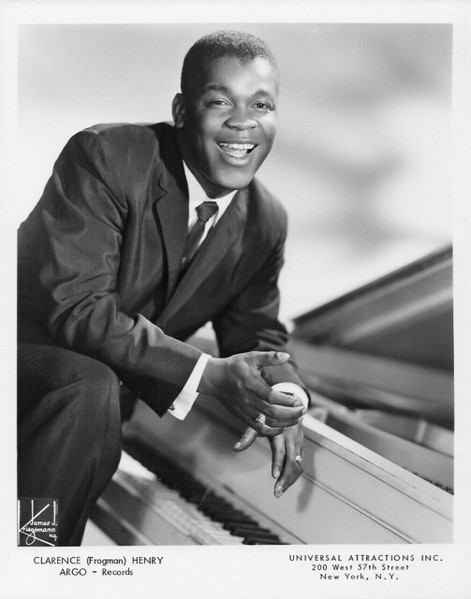

Early promotional photo.

William Houston, Henry’s music teacher at L.B. Landry High School in Algiers (where the Henrys had moved in 1948), put Clarence on trombone in the school band and in Bobby Mitchell’s teenage R&B group the Toppers in 1952, who soon recorded with Dave Bartholomew for Imperial. “[One night] at the Fun Pavilion in Raceland, Bobby didn’t show up, so they told me: you sing. I started singing ‘I Got a Woman’ and all that stuff, and the people just went haywire.”

“’During school, about two months before I graduated, I had a shotgun wedding. On the night of my wedding [April Fool’s Day, 1955], we were supposed to play at Tony Amarico’s club on Royal Street and I couldn’t make it.” Fired by Bobby, Clarence was forced to find his own small gigs. Working for Pops Marcello at the Joy Lounge, Henry and the house group, consisting of Eddie Smith (tenor), Walter Epps (guitar) and Eugene Jones (drums), played all-night gigs that one night culminated in a song.

“One night we started at nine o’clock and it must have been about six or eight o’clock in the morning, ’cause the sun was out and we was still playing. Every time it was time to get off, this guy would walk outside the club. I was angry, but I couldn’t say anything to him [Eddie], ’cause he was my leader, so I just hit the piano—BAM! ‘AIN’T GOT NO HOME!’ I was telling the people I wanted to go home, and I started singing ‘You ain’t got no home’— the man, the chicken, the frog and everybody.”

Recordings

Paul Gayten, a popular bandleader and producer for Chess Records in New Orleans soon heard the song: “He was playing every Monday night in my place at the Brass Rail. I just fell in love with him when I heard him singing that song. We took him into the studio. You know what? They didn’t want me to cut “Ain’t Got No Home.” And that was one of the biggest records of that year. Nobody said that would be a hit.”

Frogman recorded the song with his band, plus Lee Allen (tenor saxophone), Edgar Myles (trombone), Frank Fields (bass) and Gayten (piano). “They told me to take out the chicken and all this other stuff,” says Henry, “so we worked it up pretty good, and I went in on September 1956 and recorded ‘Ain’t Got No Home’ and ‘Troubles, Troubles,’ and they had me on a trial disc. The leading disc jockey here in New Orleans, Poppa Stoppa on WJMR, [got requests for] ‘The Frog Song’ by ‘The Frogman’—they didn’t know who was singin’ the song. That’s when Poppa Stoppa said, ‘Your name is ‘Frogman Henry’.”

“Ain’t Got No Home” made number three on the R&B charts in early 1957, and in New Orleans, Frogman actually kept his idol Fats Domino out of the number one spot for a week.

“I went on my first tour in January 2, 1957, at the Apollo Theatre with Clyde McPhatter, the Big Bopper, Buddy Holly, the Spaniels, and—oh! we had a big show!”

Henry and his band learned something about homelessness in those days of segregation: “I came through the era [and learned] that when you’d travel on the road there was no place for you to eat. I’ve seen my band and me come all the way from Columbus, Ohio eating Lance cookies and Coke when we could catch it in service stations outside. A lot of service stations we couldn’t use the restrooms—we had to stop on the highway and relieve ourselves. And to sleep, a lot of times we stopped on the highways and slept on the road. We couldn’t find places to sleep.”

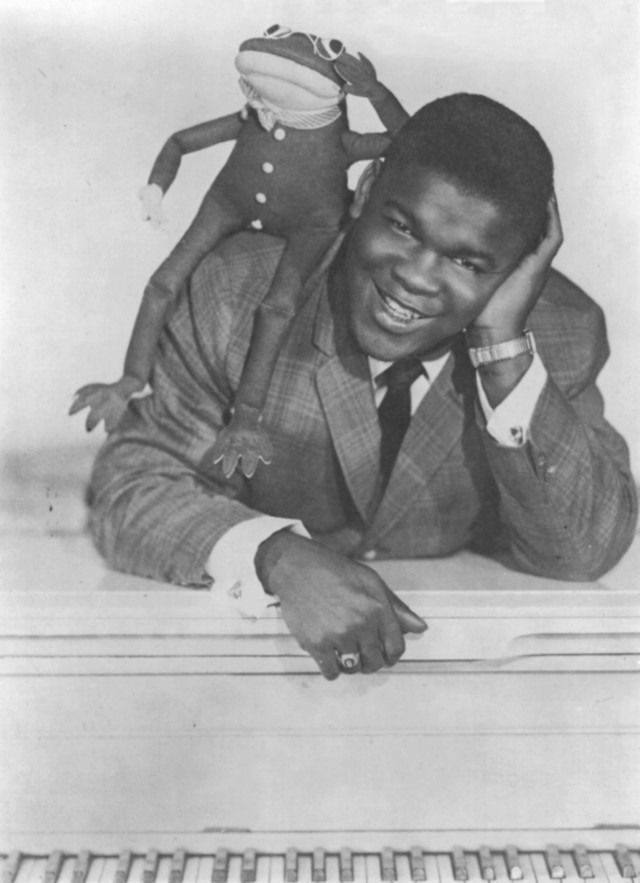

Early promotional photo.

One of the most interesting road trips Frogman made during this time was his first overseas trip to Jamaica with Bullmoose Jackson, Lewis Lymon & the Teenchords and Edna McGriff in September 1957. Local teens loved New Orleans sounds: “‘Blueberry Hill’ was the biggest thing over there,” recalls Henry, “and I sang it.”

Leonard Chess decided to record Clarence again in August 1960 with Allen Toussaint producing. “(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do” was written by Cajun Bobby Charles of “See You Later, Alligator” and “Walking to New Orleans” fame for his mother when she was dying. “I sang ’em this song,” says Charles, “and they liked it. Allen Toussaint did a great arrangement on it, and it was a big record.”

“(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do” went all the way to number four on the pop charts in the spring of 1961, causing the lonely frog to spend the honeymoon for his second marriage with Dick Clark and his Caravan of Stars. He was on tour in Chicago when Toussaint was flown up to supervise the session that produced Henry’s version of the Mills Brothers (and Bobby Mitchell) song “You Always Hurt the One You Love,” which made number 12 in the early summer. Henry had some success with other Bobby Charles songs, the best of which was “The Jealous Kind,” and stayed on the road.

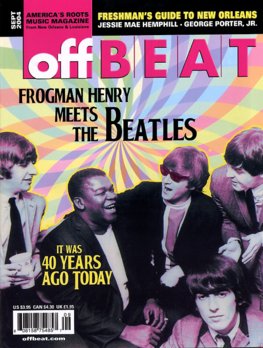

The Beatles

In 1964 Henry was chosen as the opening act for the Beatles. He opened 18 concerts for the Beatles, including a September 16, 1964, show in New Orleans at City Park Stadium.

For the September 2004 issue of OffBeat, the 40th Anniversary of the Beatles tour, Michael Hurtt interviewed Henry: “I met the Beatles around ’61, through a promoter in England,” remembers Henry, who was touring Great Britain when he made their acquaintances. “He took me to an upstairs club in Piccadilly Circus where they were playing and introduced me to them.”

The Fab Four’s adoration of the Frogman was no surprise; after all they knew their American rhythm and blues and rock ’n’ roll inside and out and were hardly secretive about their musical fanaticism. But as fate would have it, Frogman’s longtime manager also happened to be Bob Astor, who worked for NEMS Enterprises, Ltd., the organization responsible for bringing the Beatles to the States in 1964.

“Bob Astor was bringing the Beatles over,” says Henry of that first tour, “and they had a West Coast tour and an Eastern tour. He put me on the Eastern tour. Our first show was in Philadelphia, and we did 18 dates—Montreal, Toronto, New York, Chicago, all the way down to Florida.” Frogman’s contract for the tour guaranteed his services for $750 a week. After expenses, Frogman says, “I wasn’t making but $500 a week, but I enjoyed that $500! A lot of entertainers wanted to do it for nothing.”

“I saw things with the Beatles that I had never seen before on tour,” he says today. “Doctors and nurses and ambulances all around at every show. A lot of towns put us out, we’d get in there and they’d get us out of there. We’d play, but after we finished, that was it: get to the plane and get to the next city.”

In the past two weeks, there had only been two days off, spent memorably in Key West, Florida on September 9 and 10. “We stayed in a hotel and just viewed the city, and we got to be a little closer then,” he remembers. “Paul, he was my main Beatle that was real friendly, he’d ask me about different New Orleans musicians. He and I and one of the guys with the Bill Black Combo, we bummed together.

“We had a nice time in Key West; I don’t think anyone knew we were down there. We played dice but Paul was winning all the money. At one point we tried to have a jam session but I don’t think the Beatles knew too much about music at the time; all they knew was what they played. I was trying to get them to do like the Jimmy Reed or the Bill Doggett beat, things like ‘Honky Tonk,’ but they weren’t too familiar with the blues then.”

The next scheduled rest day was to be the day after the New Orleans show, but Frogman’s hometown visit—and the Beatles’ Crescent City experience—was cut short when word arrived that they would now be flying to Kansas City immediately after the City Park concert. “I brought all my clothes home with me because they said we were going to stay overnight. Then I got a call before the show telling me to bring my clothes to the concert with me.”

Clarence “Frogman” Henry’s lucky piano Photo: OffBeat/ Elsa Hahne

Bob Astor

In the OffBeat, March 1996, interview by Rick Coleman, Frogman talked about his manager Bob Astor. “Bob Astor was my manager since he met me at the old Joy Lounge until he died in ’84. We had some wonderful times together. We’ve been all over the world—New Zealand, England, Germany, Ireland, the Fiji Islands, New Guinea, Jamaica, Canada—and he put me on some big shows, a lot of shows maybe Fats Domino didn’t work on, and it made me feel proud. I worked with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Dick Clark, Paul Anka, the Shirelles, Ray Charles, Etta James, Duane Eddy, Brenda Lee, Little Richard, Jackie DeShannon…

The Beatles Impact

Henry, interviewed in OffBeat, talked about the impact on music that the Beatles had. “After the Beatles tour, I went back to playing on Bourbon Street and suddenly everything was guitars. Before the Beatles, you couldn’t catch a musician who wasn’t well-dressed, with a suit, a uniform or something like that. The Beatles dressed well, but some of the other British groups didn’t. After the Beatles came along musicians started playing on stage with their shirts busted open. And then they had the long hair, and all the kids in the world started wanting long hair. See,” he says, smiling, “My hair didn’t grow too long.”

“The British put a hurt on us,” he concludes. “It lasted a few years but we got it back. But I really enjoyed the Beatles’ music, it was something new and something different. Touring with them was a great experience but I never knew it was going to be like that. It really was comical.”

“I’d heard the Beatles before they got on Ed Sullivan and I thought they were really refreshing because they incorporated rhythm and blues as well as pop elements and so much of the old and the new. It was totally unique and seeing it during my formative years as a musician, I embraced it. I didn’t look at it as a threat to what I was doing, I looked at it as something I could add onto. I thought, ‘Hey, I’m not just a guy who can sound like Wilson Pickett or James Brown, I can do this too!’ But I really had a passion for the music. You know, there’s always been criticism saying people should stay true to their art no matter what fad comes along but I didn’t look at the Beatles as a fad. I looked at them as a band who revolutionized popular music. I saw it first-hand when I saw the hysteria in the crowd at City Park. I knew right then and there that this was gonna be one of the biggest things ever to hit the music scene.”

Clarence “Frogman” Henry, 1979 Photo by Paul Harris

Bourbon Street

Henry was unable to follow up on his hit, and lived through some hard times as a laborer until Frank Carracci hired him, first at the 500 Club and then at the Court of Two Sisters in the French Quarter.

Henry played three different Frank Carracci clubs in the ’70s and released another good album of standards in 1979 shortly before poor health brought his six-day-a-week, 21-year Bourbon Street grind to a grinding halt.

Hurricane Katrina and Ida

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina damaged Henry’s first piano. But it was after Hurricane Ida in 2021 that his Algiers home suffered extensive roof damage which led to collapsed ceilings and a mold outbreak. His vinyl record collection was destroyed, along with all of his clothes, yet Henry continued to live in the home.

Henry rode out the storm at the home of his daughter, Cathy Henry, but returned to his damaged dwelling where he has remained since, shutting doors to the most damaged rooms and sleeping on a spare twin bed or a sofa.

In 1996, Rick Coleman in OffBeat said: There’s never been any doubt that Frogman Henry’s home and heart is in New Orleans, albeit on the West Bank in Algiers, where he lives with his fourth wife, kids, adopted kids, grand-kids and hundreds of frogs. He has been one of New Orleans’ greatest musical ambassadors, but he also takes care of his own backyard. He participated in the New Orleans Artists for the Hungry and Homeless concerts, and he is an easy mark as landlord of his own apartment buildings. “I only evicted one in the whole 10 years. I had to put his stuff out on the street. Most of the guys, sometimes they owe me a year’s rent or so… I know how it is to have hardship.”

Clarence “Frogman” Henry. Photo: OffBeat/ Elsa Hahne

OffBeat Lifetime Achievement Award

In 2012 Clarence “Frogman” Henry received OffBeat’s Best of the Beat Lifetime Achievement Award. The awards that year were presented to the Legends of New Orleans R&B and were shared by Al “Carnival Time” Johnson, Robert Parker, the Dixie Cups, Frankie Ford and Jean Knight.

John Swenson wrote in OffBeat: OffBeat’s Lifetime Achievement Award winners share much more than hard luck. Over the course of a period running from the 1950s to the 1970s, these musicians created a series of timeless hits that demonstrate how New Orleans R&B helped create the rock ’n’ roll era and the golden age of top 40 popular music. “Ain’t Got No Home,” “Carnival Time,” “Sea Cruise,” “Chapel of Love,” “People Say,” “Iko Iko,” Barefootin’” and “Mr. Big Stuff” are all major elements in the soundtrack of New Orleans chartbusters. The artists who made these sides share affinities that define the nature and history of New Orleans music.

Clarence “Frogman” Henry still lives on the West Bank in a modest ranch house that is a literal shrine to his most famous creation, “Ain’t Got No Home.” On the front lawn, two frog statues flank an icon of the Virgin Mary painted in matching green. Inside the house are thousands of pieces of frog memorabilia. “People keep sending them,” he explains, gesturing at the hundreds of frog pictures, figurines and toys neatly arranged on top of and underneath the grand piano in his living room and all over the walls and mantelpieces. “I have my own museum here.”

Many of the key songs associated with these artists were recorded in Cosimo Matassa’s J&M Studio, one of the physical birthplaces of rock ‘n’ roll.

“Cosimo was it,” says Henry. “Cosimo had the studio down on Governor Nicholls Street. Both ‘Ain’t Got No Home’ and ‘(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do’ were recorded there. Everybody around the world wanted that sound. Little Richard and a lot of other people came down here to record at Cosimo’s to get that sound. That little studio had a sound that nobody could get anywhere else. They would come here to New Orleans to get that backbeat, that Caribbean feel.”

No more hits, declining health

Although Henry failed to have another hit record, “Ain’t Got No Home” continued to enjoy success in movies. The song was included in 1987’s The Lost Boys and in 1995’s Casino.

Even as his health declined and he had to rely on a walker or wheelchair, he continued to make occasional appearances onstage. After the OffBeat Lifetime Achievement Awards to the Legends of New Orleans R&B, The New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival started booking “The New Orleans Classic Recording Revue” each year since. In the upcoming Jazz Fest Bible this year, on April 25, the revue included Frogman with many more in a tribute to Jean Knight, who passed away last year.

Besides OffBeat’s Lifetime Achievement Award, Henry was recognized by the Rockabilly Hall of Fame. In April 2007, Henry was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame.

Henry was married and divorced seven times. He was still in high school the first time he tied the knot.

Facebook tributes

Goodbye to the very last of my piano friends and heros. Clarence ‘Frogman’ Henry, thank you for being a friend.—Davell Crawford

RIP Clarence Frogman Henry.—Carlo Ditta

We’re mourning the loss of Clarence “Frogman” Henry, one of the great personalities in New Orleans music history, who passed away last night at age 87.

Henry’s nickname came from his first and best-known hit, “Ain’t Got No Home,” on which he sang, unforgettably, “like a girl” and “like a frog.”

You can find more of his biography in this promotional document, which appears to have popped out of a typewriter not too long after Corey Haim sang along to Henry’s then-30-year-old classic while shampooing his hair in the vampire movie “The Lost Boys.”

Not stated explicitly in the write-up, but implied by his smile in this publicity photo: he was a supremely warm and charming person throughout his decades-long career.

Certainly, he charmed the Beatles when he opened for them at City Park in 1964, and audiences from Bourbon Street to the Ponderosa Stomp.—A Closer Walk: Interactive New Orleans Music History Map

Rip. You gave to me joy and some wonderful memories. Thank you.—Sunny Yopack

I first saw him at his club on Bourbon. I loved him!—Nona Bolin

Got to see him when the Beatles performed at City Park in 1964.—Linda McNamara

RIP Clarence “Frogman” Henry”. Thanks for all the great songs.—Anita Huggett

Rest in peace, Frogman. Bourbon Street will miss you.—Don Matheson

My Clarence “Frogman” Henry stories: When I moved back to Algiers after my first teaching job in West Virginia for two year I was a little out of sorts.

I went to Walmart where I heard a familiar voice yell “HEY ARNOLD.” It was #Frogman from down the aisle. He waved me over and gave me a hug.

Ironically Frogman made me it feel like home again. Love you Clarence “Frogman” Henry, will miss you dearly.—Lance Arnold

My good friend Clarence “Frogman” Henry, one of New Orleans’ greatest performers for over 60 years.—Rick Coleman