Chances are that if you have an interest in blues, Cajun, zydeco or ethnic music, you’ve probably got a few Arhoolie CDs on your shelf. Chris Strachwitz, the founder of Arhoolie Records, died of complications from congestive heart failure. He was 91.

A frequent visitor to New Orleans, Strachwitz was an early supporter of community radio station WWOZ. Ironically and most deservedly at the 2023 Jazz Fest, Strachwitz was celebrated with an exhibit in the Fair Grounds grandstand displaying photographs of musicians that Strachwitz had taken.

In a 1997 OffBeat interview conducted by Jeff Hannusch, Chris Strachwitz revealed that the label’s catalog is very much a reflection of his own personal tastes. While sales are important, most Arhoolie titles only sell a few thousand copies in a year, some just a few hundred. “If I had a big hit, I’d probably ask myself what I did wrong,” laughed Strachwitz.

Chris Strachwitz and Clifton Chenier. Photo courtesy of the Arhoolie Foundation.

A native of Germany and the son of wealthy farm owners, Strachwitz was born Count Christian Alexander Maria Strachwitz in the German region of Silesia, now part of Poland. His family, displaced at the end of World War II, moved to the United States in 1947, eventually settling in Santa Barbara, California. Strachwitz had already been exposed to swing overseas through Armed Forces Radio and became a jazz fan after seeing the movie New Orleans, a 1947 musical featuring Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday. He also felt a strong kinship with country and other forms of “hillbilly music.”

“I felt it all had this kind of earthiness to it that I didn’t hear in any other kind of music. They sang about how lonesome you are, and how you miss your girlfriend and all these other things,” Strachwitz told NPR. “Those songs really spoke to me.”

As a fan of Jelly Roll Morton, King Oliver and Bunk Johnson, New Orleans was a natural destination for Strachwitz, who first visited the Crescent City while on leave from the U.S. Army in the mid-1950s.

“A lot about New Orleans has changed since then, but a lot of it remains the same,” said Strachwitz. “There’s plenty of great music here, but there’s plenty of bad music too. Unfortunately, the bad music gets most of the attention because it gets played in the tourist joints.”

When Strachwitz started Arhoolie in 1960 (Arhoolie is an African word meaning “field holler”), his initial releases were recorded on field trips to the South. His travels would lead him to South Louisiana, where he recorded the Hackberry Ramblers. Strachwitz also made several of the earliest zydeco field recordings, taping Sidney Babineaux, Willie Green and Herbert Sam. Strachwitz also traveled to Mississippi and Texas taping little-known artists in their home environments, be it a dance hall, a front porch, a beer joint, a backyard. “My stuff isn’t produced. I just catch it as it is,” he explained in the 2014 documentary “This Ain’t No Mouse Music.”

For several years Arhoolie was a struggling blues label. However, in 1964 Strachwitz met the artist who would changes his fortunes—Clifton Chenier.

“I was in Houston visiting Lightnin’ Hopkins,” recalled Strachwitz. “One night Lightnin’ said, ‘Let’s go see my cousin Cliff play.’ I’d heard of Clifton before because I had a few of his Specialty 78s, but I considered that stuff R&B.

Photo courtesy of the Arhoolie Foundation.

“We walked in a joint and there was Clifton playing some real low-down blues and old-time zydeco. Lightnin’ introduced us, and he told Clifton that I made records. Clifton said, ‘Make one on me.’ He hadn’t recorded in five years, and he needed a single for the jukeboxes so he could get more work.

“The next day we went in the studio and cut ‘Ay Ai Ai’ and ‘Why Did You Go Last Night.’ The Houston distributor sold about 1,000 singles so I did a little better than break even. I came back the following year and did his first album, Louisiana Blues and Zydeco.”

As events transpired, Chenier and Strachwitz’s meeting was a turning point for both men. Arhoolie went on to develop a rich catalog of Louisiana music and Chenier was the label’s top-selling artist. In all, Chenier recorded nearly a dozen Arhoolie albums on his ascent to the role as king of zydeco.

Strachwitz recorded other zydeco artists, including the Sam Brothers, John Delafose, Bois Sec, Canray Fontenot and C.J. Chenier, Clifton’s son.

Arhoolie also developed a top-notch roster of Cajun artists. Marc Savoy and his various musical aggregations have kept traditional Cajun music alive, while Michael Doucet and his group BeauSoleil became popular on a national level by experimenting with the folk music of South Louisiana.

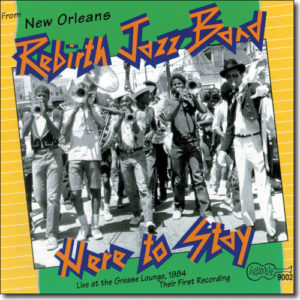

Rebirth Jazz (Brass) Band’s first record on Arhoolie Records.

In fact, two of Arhoolie’s current bestsellers [at the time] are Cajun titles—The Best of Beausoleil and Savoy’s Cajun Hot Sauce. Arhoolie has also just reissued Joe Falcon’s essential Louisiana Cajun Music, which Strachwitz recorded at the Triangle Dance Hall in Scott, Louisiana in 1963. Austin Pitre’s Opelousas Waltz has also been reissued.

Arhoolie also recorded Here to Stay, the Rebirth Brass Band’s first LP, labeled “Rebirth Jazz Band.”

“I recorded that live at that funky Treme joint [the Grease Lounge] in the mid-1980s,” said Strachwitz. “They [Rebirth] really had a lot of energy then. It might not have been their best seller, but I thought it was their best record. Later they added a saxophone and that changed the whole sound and style the band had.”

Arhoolie releases were cherished by blues fans in England, including Keith Richards. At that time Strachwitz recorded bluesman “Mississippi” Fred McDowell that included an old spiritual, “You Gotta Move.” The Rolling Stones sang a few lines from it during the 1970 documentary “Gimme Shelter” and recorded a cover that appeared on Sticky Fingers. Strachwitz prevailed over the resistance of the band’s lawyers and ensured that royalties were given to McDowell, who was dying of cancer.

Strachwitz amassed a vast catalog of blues, Tejano, folk, jazz, gospel and Zydeco, with Grammy winners Flaco Jimenez and Clifton Chenier among those who later attracted wider followings. An Arhoolie 50-year anniversary box set featured Maria Muldaur, Taj Mahal, Savoy Family Band.

Strachwitz and Les Blank produced two documentaries of traditional music Chulas Fronteras, a film about the Mexican American music of Texas, and J’ai Été Au Bal, a film about the Cajun and Creole music of southwest Louisiana.

The National Endowment for the Arts awarded him a National Heritage Fellowship in 2000. The Recording Academy gave him its Trustees Award in 2016. Strachwitz also received a lifetime achievement award from the Blues Symposium and was inducted as a non-performing member of the Blues Hall of Fame.

“No one has meant more to the preservation and appreciation of Americana roots music than Chris Strachwitz,” Bonnie Raitt wrote in Arhoolie Records’ Down Home Music: The Photographs and Stories of Chris Strachwitz, a book to be published by Chronicle Books this October.

Arhoolie Records was acquired by Smithsonian Folkways in 2016. The non-profit Arhoolie Foundation will continue its work of preserving and documenting traditional music.