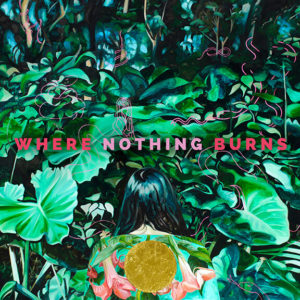

The debut LP for the alternative rock five-piece band Where Nothing Burns is full of lush instrumentation and high-caliber production, but it’s hard to measure where it fits in the modern rock landscape. Much of the band grew up in the ’90s and they openly display their affinity to influential bands like Afghan Whigs, Jane’s Addiction and Fugazi.

The debut LP for the alternative rock five-piece band Where Nothing Burns is full of lush instrumentation and high-caliber production, but it’s hard to measure where it fits in the modern rock landscape. Much of the band grew up in the ’90s and they openly display their affinity to influential bands like Afghan Whigs, Jane’s Addiction and Fugazi.

Pat Condon and William Gilbert of Metronome the City, another local ’90s-inspired alt-rock band, play in Where Nothing Burns and much of this LP feels indebted to the production and style of Metronome the City. It may be unfair to compare the two, but it’s hard not to see the overlap given so many linking factors. Besides the obvious shared band members and similar-sounding music, they share similar hurdles too. They’re playing a style of music that’s simultaneously oversaturated and underappreciated. Metronome the City seems to have found a niche art-rock identity with its repetitive, “sound of the city” approach. Where Nothing Burns follows, seeking a more accessible sound that is as futuristic as it is nostalgic.

The result is a collection of sleepy ballads with a profoundly layered sound that offers the potential to be transcendent but usually winds up ordinary. There are highlights like “Soul Sang,” where a looping drone builds a weary but stubborn momentum, carrying the song forward like a soundtrack to the Sisyphus myth. “Sit 2 Pop” has a memorable chorus featuring dueling bass and guitar, creating an intricate but catchy melody. But it takes a minute for the song to build up, which brings me to another issue with the album—every song is at least a minute too long.

The eight-track album has a nearly 43-minute run time, which by ’90s standards isn’t too bad, but in the age of streaming and ever-shrinking attention spans, the meandering blunts the sharp songwriting. The longest recording, “Carpenter,” seems like a slow-burning track with teeth, but it’s hard to appreciate it when even the fast and loud tracks are just as long-winded.

It makes sense why Where Nothing Burns’ first album would lack a unique identity and concision. But that muddiness makes you say, “This is okay,” rather than “This is great.”