It tells a lot that the title of this biography of the late, legendary Chuck Berry doesn’t mention that he was considered an originator of rock ’n’ roll. Without a doubt, the book includes information on his huge role as guitarist, vocalist and composer who contributed to the major change in the direction of music from blues and rhythm and blues to rock ’n’ roll that led to his “cross-over” audiences throughout the 1950s and beyond. Yet author RJ Smith also delves deeply into Berry as a brilliant though often contradictory, often befuddling and certainly a secretive man as well as the racial climate in his hometown of St. Louis and across the United States.

Through Smith‘s extensive, well-documented research, interviews and archival material plus quotes from Berry obtained from his 1988 book, Chuck Berry – The Autobiography, the complexity of Berry who, most people know as a world-renowned musician with, well, some very undesirable missteps, is more fully revealed.

Berry, a gearhead and poet who was way into technology, calculated his musical presence in order to achieve his desired goal of success both financially and in reputation. Diction was of utmost importance to him, a lesson promoted by his mother. Vocalist and pianist Nat King Cole became his guiding light in making sure the words to his lyrics were distinctly enunciated and understood.

Berry’s big break came after he headed to Chicago and met the legendary guitarist, vocalist and composer Muddy Waters who introduced him to Leonard Chess of Chess Records. In 1955, he recorded “Maybellene” which rose to number one on Billboard‘s rhythm and blues charts. The rock and roll revolution began with Black and White audiences—sometimes separated, sometimes sharing the dance floor—digging the new sound.

New Orleans naturally plays a role in the volume just as it did in the history of the rock ’n’ roll era. We find Quint Davis, the producer of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival and who once managed a European tour for Chuck Berry, sharing a jail cell with the star. Berry had physically attacked a photographer for having broken one of his steadfast rules—no offstage photos.

There are other scattered references to the Crescent City most notably the dispute between this city’s own, trumpeter and composer Dave Bartholomew and Berry about the ownership of the song “My Ding-A-Ling.” Bartholomew released a 45 rpm of the same name in 1952 and 20 years later in 1972, it appeared on Berry’s album The London Sessions. It was then put out as a single and it rose to number one on the charts. Considering all of Berry’s great hits like “Johnny B. Goode” and “Roll Over Beethoven,” it seemed regrettable to many that the rather sexually suggestive novelty tune was Berry’s only number one record.

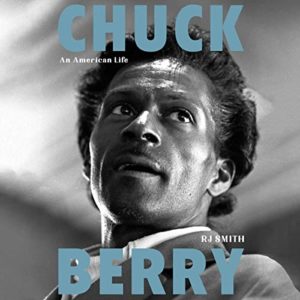

In “Chuck Berry: An American Life,” author RJ Smith puts Berry’s many talents as a musician, composer, and businessman on display as Berry goes through life as a Black man in a Jim Crow world. Yet despite his fame and fluctuating fortune, Berry was often his own worst enemy particularly when it came to his fascination with underage, white girls—a deep flaw that landed him in jail several times. As bright as Berry could be smiling as he famously duck walked across a stage with his guitar screaming, he had a dark side that could emerge at, seemingly, any given time. The dichotomy leaves fans of Berry and his music the question of whether one can dig an artist’s talent while despising some of their hateful traits. Love him or leave him, Chuck Berry was an exciting, innovating pioneer of rock ‘n roll music.

As the lyrics to his song “School Days” declare, “Hail, hail rock ’n’ roll!”