“Most of it was recorded in 1989. I was in New York, making friends with people in the anti-folk scene. During the mid-’80s a few people got together—Roger Manning, Brenda Kahn, Lach, Kirk Kelly—and there was a scene on Avenue A, an old lady named Sophie owned the bar called Sophie’s. They’d push aside the pool table and you’d stand under a bare naked lightbulb. Everybody got three songs, then they’d stay, nurse their beers, critique your songs and cheer you on. The first night I walked in, the MC was John S. Hall from King Missile, and people were shouting at him to read something. So he read, ‘Cut off my penis, didn’t need it anyway…’ And I thought, ‘I’m home.’

I got an audition with CBS Records, they turned the death clamp on me and said, ‘See what you got, kid.’ And I got a contract, but then Tommy Mottola was fired, and the new label head released all the acts. So before I left New York to move back to New Orleans I went to Roger Manning’s house, sat on the floor, recorded every song I had, and used that as a demo tape for years. Then in 1992 I’m playing with Cowboy Mouth and a woman comes up to me and says, ‘You look like you’re in a terrible mood.’ And I said ‘I don’t like the band I’m in, I’m a songwriter and nobody cares.’ So I gave my tape to this woman, Cathy Hendrix of Little Fish Platters, and she wanted to put it out. I said ‘Great, let’s book studio time.’ And she said ‘No, the guy on this tape believes nobody in the world will ever hear these songs. That’s desperation we’ll never capture in the studio.’ So the only real studio recordings are three songs that we didn’t quite get right on the tape. And I added the instrumental, ‘Carl Calls Kristie,’ because Cathy thinks every album needs to have one.

I got an audition with CBS Records, they turned the death clamp on me and said, ‘See what you got, kid.’ And I got a contract, but then Tommy Mottola was fired, and the new label head released all the acts. So before I left New York to move back to New Orleans I went to Roger Manning’s house, sat on the floor, recorded every song I had, and used that as a demo tape for years. Then in 1992 I’m playing with Cowboy Mouth and a woman comes up to me and says, ‘You look like you’re in a terrible mood.’ And I said ‘I don’t like the band I’m in, I’m a songwriter and nobody cares.’ So I gave my tape to this woman, Cathy Hendrix of Little Fish Platters, and she wanted to put it out. I said ‘Great, let’s book studio time.’ And she said ‘No, the guy on this tape believes nobody in the world will ever hear these songs. That’s desperation we’ll never capture in the studio.’ So the only real studio recordings are three songs that we didn’t quite get right on the tape. And I added the instrumental, ‘Carl Calls Kristie,’ because Cathy thinks every album needs to have one.

I was working in New York on a Matt Dillon movie, A Kiss Before Dying, as a production assistant. I was staying with some friends who’d just fallen in love and were making a lot of noise about it, and I was getting divorced so I wasn’t in the mood. I started going for walks and one night I walked from Avenue A to Houston Street, and decided I’d drink a shot at every bar along the way—not realizing there are more bars per capita in the Village than there are in New Orleans. It was a very long walk. And when I got back to the apartment, drunk as a coot, I grabbed my guitar, went up on the roof and wrote ‘Light It on Fire.’ We did that song in Cowboy Mouth, because when we started out we were all doing songs from our backgrounds. I remember saying to Fred, ‘We should do that song “Jenny Says.”’ And he said ‘No, we can’t do that, it’s a Dash Rip Rock song.’

‘Picture of You Wearing Bones’ is literally about mentally picturing somebody dead—that’s a very New Orleans way of expressing anger. ‘Louisiana Lowdown and Blue’ is one I wrote in New York, I’d been listening to the Neville Brothers’ album Neville-ization and trying to riff on Bob Dylan’s guitar lick from ‘Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again.’ So that’s where the riff in my song comes from, even though it wound up sounding nothing like Dylan.

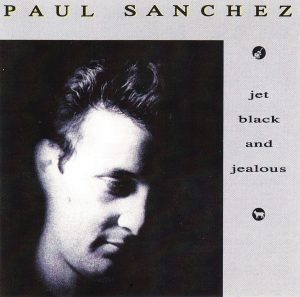

We didn’t do ‘Jet Black and Jealous’ in Cowboy Mouth because it wasn’t a rocker—but ironically enough, when the Eli Young Band covered the song [in 1998], they rocked the hell out of it. The cover came at a really good time for me—the flood had happened, I’d left the band and I was lost, so I got a song on the country charts while I was getting my life together. When I heard Eli Young’s version I thought it was so different that it wasn’t even my song. If they’d just put it out I wouldn’t have recognized it.

This album showed me how easy it is to put out a record; up until then I’d been waiting for permission. It happens to be my most popular CD and a few of the songs got used on Mouth records, so that gave them a second life.

All my songs are my life story, it’s all one song that I started writing when I was six. Songwriting for me is the easiest thing on the planet—it’s the rest of life that’s the challenge.”