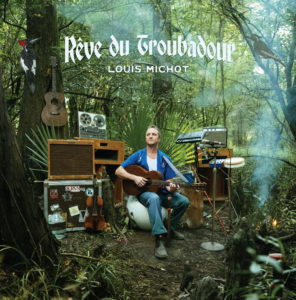

Anyone familiar with the career progression of Lost Bayou Ramblers’ fiddlin’ frontman Louis Michot can sense he has plenty to say and seemingly infinite interests. That’s certainly evident with his solo debut, Rêve du Troubadour, an eclectic, genre-defying blockbuster atypical of his Lost Bayou Ramblers, Les Frères Michot and other groups along the way.

Michot began this project during the languishing months of the pandemic, rising in the early morning hours to record his nonstop ideas in a dry-docked backyard houseboat studio. Before the sun was in the sky, he had often finished something destined for Rêve. Though Michot’s known for his rustic, Creolesque fiddling style, here he plays more guitar, electric and acoustic, fulfilling the image of a true, guitar-equipped troubadour. Additionally, Michot contributed bass, steel guitar, accordion, t-fer (Cajun triangle), snare drum and electronic beats to the album.

While a couple of tracks feature him solo, the rest is a consortium of various bandmates and a diverse set of guests like cellist Leyla McCalla, electro-beat wizard Quintron, Shardé Thomase (with/without her North Mississippi Drum and Fife group) and Nigerian Tuareg guitarist Bombino.

Michot starts with a root of Cajun music “Amourette,” originally recorded as “Mademoiselle Emilie” by a cappella ballad singer Julien Hoffpauir in 1934 by John and Alan Lomax. He crafted a driving fiddle line over Quintron’s infectious bed of beats for an intriguing juxtaposition of the ancient and contemporary.

Yet, the point Michot makes here is not how he stays within his wheelhouse but how far he ventures from it, such as interpreting 19th-century Creole composer Louis Moureau Gottschalk’s “Souvenir de Porto Rico” on a fat, fuzzed-tone guitar. Listen closely, and you’ll hear the ethereal string-sharding of McCalla and violin duo String Noise.

Though Michot estimates he has published over 100 songs, Rêve finds him growing as a profound French songwriter. On the surreal title track, “Rêve du Troubadour” (“The Troubadour’s Dream”), Michot whistles a melody based on “The Cherokee Waltz” before eloquently stating his violin is his saber and his pen a dagger. Thomase repeats the theme on fife, drawing a Celtic connection to the age-old Cajun melody.

Interestingly, a couple of compositions are historically-based. On “Jean Cuan dit Gentil,” Michot solemnly sings in a low register about a Frenchman who married a French Creole in Alabama and resettled his family in La Coquille, a town he founded, now Madisonville, Louisiana. That led to Michot’s discovery of Marguerite, an enslaved African-born woman who was liberated thrice. The resultant “Le Cas de Marguerite” features Bombino’s searing guitar work, the rustling of clackety beats, and Michot’s conviction-filled vocals for a spellbinding listen.

Stylistically, few stones are left unturned. For something mind-boggling, check out “Boscoyo Fleaux” that’s even more ground-breaking than “Marguerite.” Michot’s spacey rapping and avant-garde saxophonist Dickie Landry’s abstract bops, squawks, shrieks, and squeals push it to the edge, something not for the faint of heart. “Ti Coeur Bleu” is poppy and jangly enough to feel at home on French Canadian alternative airplay.

On the last couple of tracks, Louis Michot returns to his wheelhouse with more surprises. He plays solid zydeco accordion on “Acadiana Culture Backstep,” an enticing dance number whose lyrics question if his culturally celebrating area is genuinely inclusive or held back by provincial mindsets. “Tchén-Ka-Yay (Chanquaillier)” is an eerie cross between a forgotten field recording and the marvels of studio mastery. Columbus Frugé, an accordionist who waxed four sides for Victor in 1929, speaks of his early life sandwiched between Michot’s alternating drum machine tones and ringing fragments of Frugé’s “La mazurka qu’a capoter Lina.”

If these are Michot’s dreams, who’d ever want to wake up?