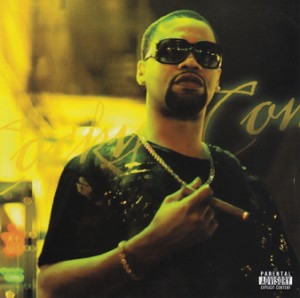

Has Juvenile ever not sounded cocky and confident? If the title of his new album tells us anything, it’s that he’s in his comfort zone as a high roller from the Magnolia Projects. He pursues the usual obsessions—particularly getting paid—and his musical world remains the same—the hood. What the album shows is how reliable his musical sense is. On first listen, I tried to figure out what the hit is supposed to be, and after hearing four or five bangers, I gave up and checked the label’s hype sticker. “New Orleans Stunna” is made to blast out of car stereos, and Kango Slim’s dancehall chorus on “We Be Gettin’ Money” is hard to forget. I can even imagine the Auto-Tuned slow jam “All Over You” being a hit, though it’s the most generic track on the album (love doesn’t seem to inspire Juvie much).

Has Juvenile ever not sounded cocky and confident? If the title of his new album tells us anything, it’s that he’s in his comfort zone as a high roller from the Magnolia Projects. He pursues the usual obsessions—particularly getting paid—and his musical world remains the same—the hood. What the album shows is how reliable his musical sense is. On first listen, I tried to figure out what the hit is supposed to be, and after hearing four or five bangers, I gave up and checked the label’s hype sticker. “New Orleans Stunna” is made to blast out of car stereos, and Kango Slim’s dancehall chorus on “We Be Gettin’ Money” is hard to forget. I can even imagine the Auto-Tuned slow jam “All Over You” being a hit, though it’s the most generic track on the album (love doesn’t seem to inspire Juvie much).

Because he doesn’t stray from his usual themes, Cocky & Confident isn’t going to speak to anyone who lacks patience with coarse language and ghetto themes. Still, what sets Juvie apart besides his song sense is the matter-of-fact quality of his flow. He doesn’t deliver “We Be Gettin’ Money” or “Top of the Line” as boasts; he presents them as the truth. He’s not celebrating or doing the equivalent of an end zone celebration; he raps as if he’s been there before.

That same measured quality extends to the nature of his songs. They’re ghetto-centric, but they’re not necessarily tales of crime and violence, which so often invite listeners to doubt the song and all its claims. Unlike Atlanta’s crunk crew that can’t get away from strip clubs, Juvenile doesn’t concern himself with what getting paid can get him. Instead, the songs have a zen quality as they celebrate the experience of being in a good place, admittedly by his standards.

In New Orleans in 2009 when a mixed income community is being built on the rubble of Magnolia, there’s something disconnected about Cocky & Confident, but that may be another manifestation of Juvenile’s Zen. These songs are about his now, and from minute to minute, day to day and year to year, locations change but now remains now. You can argue that it’s short-sighted, but you can’t deny that it’s true. You can, however, reasonably observe that women remain objects in his songs. In “It’s All Hood,” he can extend sympathy to a homie that’s an addict, but a woman he’s into could be “a side dish with my steak.” Still, this is about his now, not hers. That blind spot is an obstacle between him and a larger audience, though, and there’s enough here that’s right that it’s easy to imagine him being more than a hood success story if he could only join the 21st Century.