For musically oriented readers, Ned Sublette’s book, The World That Made New Orleans: From Spanish Silver to Congo Square is arguably the best account of the origins of New Orleans. By combining deep historical analysis, erudite musicology and a thorough understanding of cultural influences, he created a synthesis of ideas that will overwhelm even the most informed reader with new information. Joe Boyd

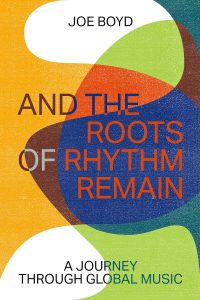

Now along comes Joe Boyd’s And the Rhythm Remains: A Journey Through Global Music, which accomplishes the same feat, but covers so much more ground. At over 800 pages, this nearly two-inch thick book is over twice the length of Sublette’s tome. It is a whopper in every sense of the word.

Boyd is not as well-known as many of the musicians who have provided cover blurbs for his new book, a follow-up of sorts to White Bicycles, his memoir of the 1960s, including Robert Plant, David Byrne, Brian Eno and T Bone Burnett. But his history as tour manager for Muddy Waters and Sister Rosetta Tharpe and as a producer for musicians as varied as Cubanismo!, R.E.M., early Pink Floyd and Toots and the Maytals is unparalleled.

The book is organized by country and region and begins where it all began in Africa. He takes us on a journey to Cuba, Jamaica, Brazil, Argentina, India, Eastern Europe and the continent and to points in between before returning us back to Africa. By the end of this hefty volume, Boyd has managed to explain in deep, yet easy to read prose the history of world music and all of its myriad connections.

He is an idiosyncratic writer who drops hints in every introduction of a new player that becomes like a game for music lovers—who is he talking about? Is it Bob Marley or Peter Tosh? Even the most knowledgeable aficionado might occasionally be stumped only to be astonished by the reveal.

The same goes for his explication of the history and development of various styles of music. You may be aware that African rhythms traveled across the Atlantic during the Middle Passage and returned after seeding the Americas only to be transformed again in the hands of more modern-day West Africans like Fela Kuti, Taby Ley Rochereau and Franco. But did know you that so-called gypsy jazz most likely began in the part of the world that now encompasses India and Iran? I certainly didn’t.

The Roma, the peripatetic ethnic group that invented and promulgated the style, originated geographically far to the east of the areas of Europe and the Caucasus that they populate today. Large extended families of musicians, tinkerers, peddlers and tradesmen arrived in two separate waves. During the first wave in the 1500s, they took to explaining their origins by saying they were from Egypt—an area more familiar to Europeans than the “Orient”—hence the abridged term “gypsies.” Fascinating right?

The book overflows with similar examples. Kool Herc, known as the “Father of Hip Hop,” was born in Jamaica and witnessed massive sound systems and DJs spinning long-playing jams in Kingston before he brought the concept to the Bronx and changed popular music.

Most people who love world music are familiar with the concept of the griot—a musician that is also an oral history archivist and poet in some African cultures. The term is derived from a Portuguese word meaning “court jester” or “bard.” Malians actually prefer the term “jali” to describe these individuals.

One of the other main features of the book that make it so special is Boyd’s biographical treatment of many of the artists that populate the history of world music. He adds numerous enticing tidbits to the life stories of these musicians, including well-known ones like Carmen Miranda and Marley, with lesser known, but equally as important players in the many genres he covers.

The book also overflows with historical facts and anecdotes that explain how music spread, grew and changed over the centuries. I could quibble with some inaccuracies including the contention that New Orleans was discovered by the French sailing down the Mississippi River rather than up it, as well as the short shrift he gives the city itself.

I suspect that the omission of a full chapter on New Orleans is a byproduct of the strength of Sublette’s work, which Boyd references numerous times, rather than a slight. Boyd is fully aware of the role the city plays in American music as well as its influence on the rock ‘n’ roll scene that developed in England.

The book is not focused exclusively on world music. He expounds on Eastern European orchestral ensembles and the fall of Communism behind the Iron Curtain and the development of classical composers in the 19th and early 20th centuries including our own beloved Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

Boyd touches on iconic albums such as the aforementioned work by Cubanismo!, the Buena Vista Social Club and Paul Simon’s Graceland. He does it all with wit and occasionally self-deprecating candor about his role in many of these great works of musical art.

With his label Hannibal Records, Boyd helped popularize the term “world music” along with Chris Blackwell of Island Records and the musician Peter Gabriel’s Real World Records by taking loosely connected styles and placing them under one umbrella for marketing purposes. He takes the reader through the ups and downs of sharing music from the Black and brown peoples of the world with the mostly white middle class Americans and Europeans who bought the albums. It’s a tale that is beyond fascinating, bordering on unreal. But Boyd was there, and you can be too by picking up this amazing book.

Joe Boyd