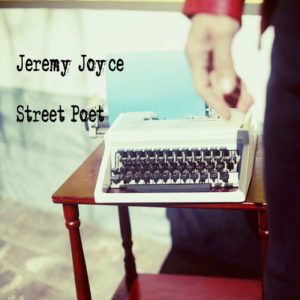

Like many New Orleans musicians, Jeremy Joyce is out there living the dream full-time in the venues and streets of the city. In doing so, he fuels his work with the sights and sounds of the city, living life as it comes. The old starving artist knows how to really live and that’s what his latest album, Street Poet, is all about.

Like many New Orleans musicians, Jeremy Joyce is out there living the dream full-time in the venues and streets of the city. In doing so, he fuels his work with the sights and sounds of the city, living life as it comes. The old starving artist knows how to really live and that’s what his latest album, Street Poet, is all about.

Joyce has a lot of ideas. I’m especially fond of his side project, JJ Shreds and the Chompers, for its wacky, over-the-top approach. And his solo work, specifically on this album, experiments with a wide range of genres important to New Orleans. He bounces around from traditional jazz to bluesy shuffle to straight R&B, giving each genre its due credit without changing the formula too much. His most original ideas seem to pop up in the lyrics and overall style each song delivers.

As JJ Shreds, his ridiculously fun premise helps cover up the derivative with funky imagination. But as Jeremy Joyce, each song brings a new context. And those contexts can be hit or miss, like “High Heel Blues,” a story inspired by Joyce’s observations on the F Train in New York City. In it, a literal starving artist finds himself daydreaming of dating a woman in a higher income bracket if only for the stability wealth provides. Alone the premise seems compelling enough but, when put to lyrics, it seems more creepy and desperate than working-class blues.

New Orleans artists who address issues of wealth inequality can be exciting when their music works in songs like “Times Like These,” which simply describes the real-world effects of capitalism and the “less-than” people it creates. Anyone who’s spent time in New Orleans has ignored these people in the streets or under the highways.

“Times Like These” is a protest song calling for change. Although a simple song musically, with an even simpler premise, the implications of its photographic lyrics make it far greater: “I’ve seen people in the streets with blood on their face/ A punk in the heat laid his body to waste/ A mother making groceries on a roll of dimes/ Wonder how she’s gonna pay the bills this time.”

“What Love Used To Be” also stood out despite being an atypical R&B track with a simple premise. Inspired by a Jon Cleary performance at Chickie Wah Wah, the track tells the story of two older, jaded people finding the courage to love again despite a history of heartbreak. A smooth sax solo delivered by Alex Geddes and backing vocals by Emily Robertson makes the song’s execution sonically robust. And Joyce’s imagery, sometimes goofy but endearing, fills the picture: “If a new branch grows from a fallen tree/ If a blind dog wags his tail at me/ If two old folks dance cheek to cheek/ Maybe love could be what it used to be.”

The album’s weakest points seem the best fit for jazz clubs rather than a studio release. Specifically, “All Night All Night,” which admittedly is a fun track, sort of feels like a throwaway. Overall, “Street Poet” does pull together a vivid picture of New Orleans from Lower Decatur to the Riverbend. But like a generic Pirate’s Alley photo sold in a Conti Street gift shop, vivid doesn’t always mean original or interesting.