Singer-pianist Henry Gray performed in Chicago and toured from the city from 1946 to 1968. During the golden age of Chicago blues, Gray played piano in the studio and on stage with Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Little Walter Jacobs, Jimmy Reed and more. He also worked in Wolf’s band for 12 years and recorded for Chess Records as a frontman.

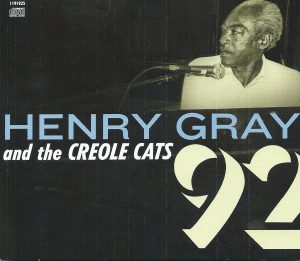

A determined man and artist, Gray, 92, keeps playing the blues. His new album, recorded in summer 2017 at Dockside Studio in Maurice, Louisiana, is titled 92.

Album co-producer Terrance Simien, a Grammy-winning zydeco artist, has the right idea for 92. He lets Gray do what he does—sing and play in the classic Chicago blues style that he made a significant contribution to.

Gray’s backing band features two especially apropos musicians. He’s worked often with Acadiana blues guitarist Paul “Lil’ Buck” Sinegal and the Phoenix-based harmonica player Bob Corritore. Simien band members Danny Williams, keyboards; Stan Chambers, bass; and Oreun Joubert, on drums step naturally in as the rhythm section.

The 92 songs will be familiar to anyone who knows Gray’s band and solo shows. He performs his signature originals, the raucous “Come On In” and Little Richard–like “Henry’s House Rocker.” Also the traditional “Stagger Lee” and a pair of Chicago standards, Big Maceo Merriweather’s “Worried Life Blues” and Jimmy Reed’s “Bright Lights, Big City.”

Gray’s vocals and piano are strong and decisive throughout the 13 tracks. He rolls through a good-rocking rendition of another of his original songs, “How Could You Do It,” playing the part of a hurt, indignant, betrayed lover with much conviction. And he’s at his best in the woeful and weary “Blues Won’t Let Me Take My Rest.”

92 further contains behind-the-scenes informality. In track five, Gray asks his musicians if they know “Corrina, Corrina.” He starts it and they jump in. And speaking to Simien, Gray explains the difference between the sacred music his father preferred and the blues Gray wanted to play. A snippet of “The Lord Will Make a Way Somehow,” which Gray uses to make his point, suggests he could have been a fine gospel artist.

Bringing Gray, Louisiana’s oldest and more storied blues artist, in the studio again at 92 was a fine idea. The resulting album is a warm, representative account of one of America’s premiere, authentic, still-rocking blues men.