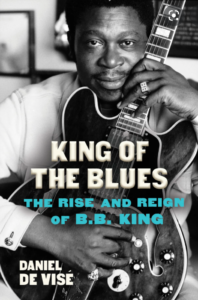

With three previous full-length B.B. King biographies still circulating, a handful of well researched box sets and any number of comprehensive B.B. King CD compilations, plus extensive stories about the man’s life in any number of publications, even the most ardent blues aficionados are bound to ask themselves, “What more can a writer discover about B.B. King’s life and career, or add/subtract from his legacy?” Turns out quite a bit according to Daniel De Vise. First of all, this is the first biography to be published after King’s death in 2015 and the book offers details about his sad final years on earth. De Vise doesn’t disregard his earliest years though. The book reveals new details about King and living in the stark poverty during the Depression years in the rural Mississippi Delta. Obviously, at an early age he found the guitar. His style developed from listening to various sources—including Charlie Christian and even Django Reinhardt—as well as hands-on teachers like Robert Lockwood Jr. and King’s cousin, the legendary Bukka White. In the end though, King developed a single-note technique that would be his signature when he began making records in 1949. De Vise points out once King began recording, for the next 50 years he basically lived out of a suitcase. In the early 1950s, hits like “Three O’clock Blues,” “You Upset Me Baby” and “Sweet Sixteen” sent him on an endless pursuit of one-nighters. During his heyday, King and his bands played as many as 340 dates a year. In those days, King’s domain was “the chitlin’ circuit,” clubs in the South and venues in Northern cities where African Americans migrated to after World War II.

With three previous full-length B.B. King biographies still circulating, a handful of well researched box sets and any number of comprehensive B.B. King CD compilations, plus extensive stories about the man’s life in any number of publications, even the most ardent blues aficionados are bound to ask themselves, “What more can a writer discover about B.B. King’s life and career, or add/subtract from his legacy?” Turns out quite a bit according to Daniel De Vise. First of all, this is the first biography to be published after King’s death in 2015 and the book offers details about his sad final years on earth. De Vise doesn’t disregard his earliest years though. The book reveals new details about King and living in the stark poverty during the Depression years in the rural Mississippi Delta. Obviously, at an early age he found the guitar. His style developed from listening to various sources—including Charlie Christian and even Django Reinhardt—as well as hands-on teachers like Robert Lockwood Jr. and King’s cousin, the legendary Bukka White. In the end though, King developed a single-note technique that would be his signature when he began making records in 1949. De Vise points out once King began recording, for the next 50 years he basically lived out of a suitcase. In the early 1950s, hits like “Three O’clock Blues,” “You Upset Me Baby” and “Sweet Sixteen” sent him on an endless pursuit of one-nighters. During his heyday, King and his bands played as many as 340 dates a year. In those days, King’s domain was “the chitlin’ circuit,” clubs in the South and venues in Northern cities where African Americans migrated to after World War II.

Then finally, in 1969, King’s unforgettable “The Thrill Is Gone” became a stepping stone to wider audiences. King would go on to preform in more than 80 countries. In fact, for my 16th birthday, my parents bought me a ticket to see B.B. King and his ultra-hip six-piece band at the Shakespearian Theatre in Stratford, Ontario. New Orleans, of course, was a regular stop during King’s career. In days when there was still segregation, he and his band would stay at Frank Painia’s Dew Drop Inn. King often cited Painia’s generosity and detailed the after-hours/early morning jam sessions organized by Patsy Vadalia in the Dew Drop’s dance hall. But in those days, King’s favorite New Orleans venue was Dave Brown’s Blue Eagle on Saratoga Street. King and Brown forged such a strong bond that Brown named his son Riley after his favorite artist. In fact, Brown’s widow still received personalized Christmas cards from King until his demise. Of course, King would graduate to larger venues here, becoming a regular at the Jazz Fest and he often appeared at the Municipal Auditorium and the Saenger Theater. His last local appearance was at the latter, sharing the bill with Snooks Eaglin. Being a longtime of fan of King, I read a couple of previous biographies and own a large number of King’s recordings on CD and vinyl. It’s hard for me to render an unbiased review of King Of The Blues. However, I enjoyed the book immensely, found lots of interest new material about the blues musician and especially found the man’s daunting—over a hundred to date—album discography informative. I would definitely recommend this book to B.B. King and blues fans as well as anyone who studies or just has passing interested in the modern evolution of Black musical culture.