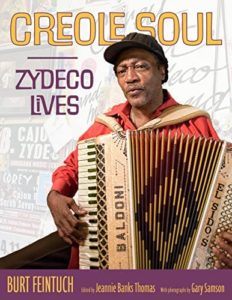

It’s always an honor whenever someone from inside the culture films a documentary or writes about their cultural music. But when someone outside the culture documents it, it becomes even more significant since it’s viewed from an unbiased, unattached perspective. Such a statement is echoed by the book Creole Soul by Burt Feintuch. In addition to being an academic and a musician, he has written about regional cultures, roots music, and North American revival music since the ’70s. This high-powered author was also a professor of folklore at the University of New Hampshire and directed the University’s Center for the Humanities. Feintuch was no stranger to Louisiana music either. He also authored the book Talking New Orleans Music: Crescent City Musicians Talk about Their Lives, Their Music, and Their City, published in October 2015.

To knowledgeably write about any cultural music, one has to experience it in its cradle since it’s practically impossible to do so from afar. That Feintuch did. In 2015 and 2017, he, editor Jeannie Banks Thomas, a Utah State University professor, and later photographer Gary Samson, tramped across Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas gathering interviews, materials, and photographs that would ultimately become Creole Soul. They bumped to the beat in zydeco clubs, hung out at trailrides, and visited subjects in their homes, not to mention the gravesite of zydeco’s founding patriarch Clifton Chenier, courtesy of musician Corey Ledet. Along the way, they made countless contacts and befriended many. Based on this exhaustive work, it’s hard to imagine any stone was left unturned.

Burt Feintuch’s Creole Soul not only documents his travels and experiences but explains the definition of Creole and describes the culture with authoritative references, indicating the project was well-researched. The bulk of Creole Soul is neatly categorized in a Texas section, followed by a Louisiana section, showcasing 11 musicians from both states. Featured Texans are Ed Poullard, Step Rideau, Brian Jack, Jerome Batiste, and Ruben Moreno. The Pelican State’s representatives are recently deceased Lawrence “Black” Ardoin, his son Sean Ardoin, Corey Ledet, Leroy Thomas, Dwayne Dopsie, and Nathan Williams Jr., also known as Lil’ Nate.

Each chapter profiles a particular musician starting with an informative introduction, so you’re somewhat familiar with him before proceeding to the interview transcription. Based on the conversational nature of these interviews, it was most likely Feintuch’s intent to present them as realistically as possible, so you feel like you’re across the table from them having a cup of coffee.

Where the rubber meets the road are the occasional insider tidbits dropped along the way. Dwayne Dopsie explains how his father, Rockin’ Dopsie, also a renowned zydeco accordionist/vocalist, was bestowed the nickname of “Dopsie” and how he feels his zydeco culture is threatened by some newcomers. The Sean Ardoin interview is insightful it demonstrates that he eventually realized his family’s generationally passed-down music could become a business as well as how Texas zydeco men typically didn’t apprentice in the family bands like many do in Louisiana. Lil’ Nate wanted to incorporate different and more complex chords than the oft-played 1-4-5 progression. Ed Poullard tells how he took up the fiddle when an injury prevented him from playing the accordion. He also shares how zydeco accordionists prefer their mics inside the box while Cajuns prefer them on the outside for a warmer tone.

As the subjects speak, you glean pieces of zydeco history, such as how Beau Jocque revolutionized the genre and how Boozoo Chavis’ hypnotic effect influenced a generation of players.

Certain themes, such as accordion and equipment preferences, differences between Louisiana and Texas zydeco, and church dances versus clubs, surface with practically every testimony.

Samson’s stunning 58-color photographs of the subjects, spectators, trailrides, performances, and action-packed dancing are a huge part of this book and its take-you-there appeal.

But perhaps the most jaw-dropping part is not anything Feintuch wrote but Jeannie Bank Thomas’ preface revealing how she finished her friend’s book after he tragically passed away. At one point in the hospital, before an operation, Feintuch requested only one thing of her as she stood beside his hospital bed: “Please finish my book.” Eventually, when the time was right, she did, but it’s scary to think how close these priceless stories came to being left untold.