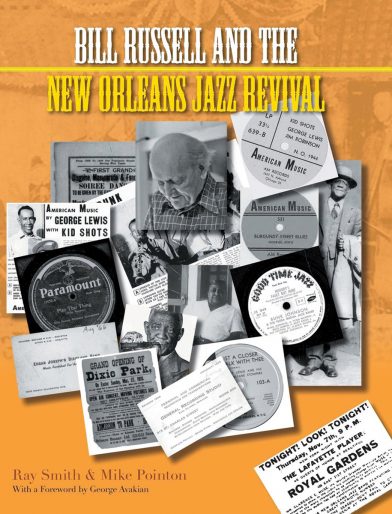

How can anyone review this masterpiece? Based on interviews conducted in 1990 by Ray Smith and Mike Pointon, it was originally intended for a BBC radio series, but with the encouragement of Ellen Smith-Asjes, has evolved into this book.

How can anyone review this masterpiece? Based on interviews conducted in 1990 by Ray Smith and Mike Pointon, it was originally intended for a BBC radio series, but with the encouragement of Ellen Smith-Asjes, has evolved into this book.

These interviews of Russell are transcribed directly from the recordings, inevitably resulting in occasional repetition in his anecdotes, but the overall effect allows the reader to almost hear the man himself talking. All the potential publishers who were approached initially wanted to edit this, but the authors declined, resulting in a delay of some 25 years in its publication. An homage to Bill Russell, the book builds a picture of this complex man by interspersing other interviews, recollections, articles, program notes and photographs, and adding reminiscences by many of us who knew him or benefitted directly from his selfless efforts on our behalf, including George Avakian, his brother William Wagner, Frederic Ramsey, Jr., Mahalia Jackson, Doc Souchon, Lars Edegran and Dick Allen.

Russell was drawn to the percussive and rhythmic aspects of jazz, notably the boogie-woogie of Jimmy Yancey and Albert Ammons, and the jazz of Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Johnny and Baby Dodds, and before the jazz of Bunk Johnson. The more he heard the drumming of Baby Dodds, the more he realized that what Baby could do on a drum set was more vital than anything he had written for percussion. Giving up composing, he devoted the rest of his life to recording and helping New Orleans musicians, especially the trumpeter Bunk Johnson.

But his contributions did not stop there. For when Bunk Johnson died in 1949, Russell, now in Chicago, assisted the great gospel singer Mahalia Jackson in the beginning of her career. However, in 1956, Russell finally moved to New Orleans where he opened a record shop in the French Quarter. This led, in 1958, to the invitation by Dick Allen and Dr. William Hogan (the chair of the History Department) to be the first curator of the Tulane Jazz Archive, with a grant from the Ford Foundation to conduct interviews with the surviving New Orleans musicians. Russell was curator for the first four years, after which Dick Allen assumed the post. The archive was later renamed the William Ransom Hogan Jazz Archive.

Bill Russell is especially revered among fans of New Orleans jazz, for he contributed so much to the growth of the worldwide interest in this music, and indirectly to the city itself. The present continuing surge of interest in New Orleans can be partly attributed to people like Bill Russell who, early on, recognized something unusual and unique in the city and its people—the city where jazz began.