Sometime in the 1980s, then University of Louisiana Professor Barry Jean Ancelet began writing French-language poetry under the nom de plume of Jean Arceneaux. Some were ultimately reworked into song lyrics; others were initially written as lyrics. Ancelet reasoned that most Louisiana French literature was consumed as song lyrics. Over the decades, Steve Riley & the Mamou Plays, Kevin Naquin, Richard LeBouef, and Jambalaya have recorded Ancelet’s lyrics. In 1991, Wayne Toups won the Cajun French Music Association Song of the Year with Ancelet’s “Late in Life.” In 2014, Ancelet’s lifelong friend, Sam Broussard, a singer/songwriter in Riley’s band, expressed interest in transforming his lyrics into musical compositions. Broussard likens his methodology to the Brazilian model of songwriting, where a composer pairs with the best lyricist possible, and for French lyrics, he estimates Ancelet is the best. Obviously, the symbiotic partnership works. Their first recording, Broken Promised Land, was Grammy-nominated in 2016.

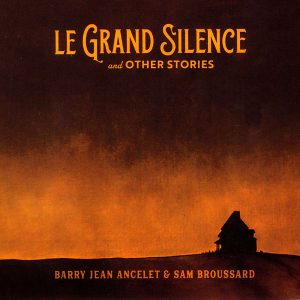

Eight years later, the duo’s highly anticipated Le Grand Silence and Other Stories not only picks up where its predecessor left off, but skips a few chapters ahead. Compared to its predecessor, the arrangements are exponentially more complex and denser. Any instrument not played by one of the seven guests—mostly drummers and harmonica players (including Zachary Richard)—is played by Broussard under the humorous summarization of “Everything but …,” as noted in the detailed liner notes. Broussard masterfully plays all guitars, bass, banjitar (a banjo tuned like a guitar), African finger piano, piano (including one with effects to resemble an accordion), fiddle and flute, and there are probably a few more wedged in there.

Broussard says his inspiration for the arrangements comes from the rhythms of Ancelet’s lyrics. The proceeding’s many themes led to Broussard’s weaving of varied and amazing textures. The haunting “Ouindégo” begins with Broussard’s hypnotic finger-picking pattern and soft, delicate vocal delivery on a tale about a mysterious children-munching swamp spirit whose invisible presence causes it to become windy. Orchestral parts float in, which also close the song with a surreal moment. “Grand Silence” is the only traditional Cajun track, a fiddle-driven waltz. It’s about finding solitude while paddling through the swamp and the tranquility and introspection it brings.

Broussard does intriguing things with his vocals and those of his participants. “Entre Deux” and “Feufollet” have shades of African American harmonies but may remind some of South Africa’s Ladysmith Black Mambazo. “J’ai Pas Fair Ça” breaks its intensity twice to shift into a melodic multi-part quasi-juré.

In the liner notes, Broussard lists himself as the light voice and Ancelet as the dark. Dark often fits Ancelet’s low register and the parts he sings, but it also is an apt description of his lyrics, such as “Ouindégo,” “J’ai Pas Fair Ça,” and “Pieds du Diable.” “Trop Jeune” describes an older man past his prime. Broussard’s rhythmic pattern on the piano’s low bass notes feels ominous, possibly that the end is near. Yet, nothing is more disturbing than the macabre “Consequénces,” a young girl is beaten senselessly to the point of madness and abandoned.

Besides Broussard singing lead on most songs and Ancelet on some, Anna Laura Edmiston is the only other lead vocalist. On tearful “Si Je T’aimais,” she is simply stunning in her admission of unrequited love. The arrangement’s pauses and swells augment the emotion portrayed.

Of the 17 tracks, only three are in English. Of these three, the slinky “Middle of the Road,” sung by Ancelet, could contend for Americana track of the year. “Rita, Come Follow Me Down,” Broussard’s original, is quite ingenious. He wrote it from the viewpoint of Hurricane Katrina, a startling contrast to the other Katrina songs. One thought expressed is hurricanes are equal opportunity employers. They don’t discriminate.

Clocking in at 75 minutes, it’s a heady listen with endless, mind-boggling details. One can always listen to it on popular streaming platforms but given the glossy 24-page liner notes with translations and edgy folk art, hardcopy is recommended for those desiring to appreciate every inch of Ancelet and Broussard’s brilliance.