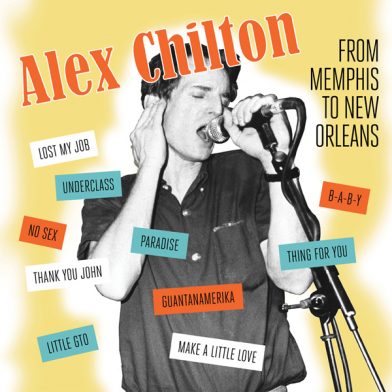

Celebrity history is filled with people who are victims of their own success. Rock and roll history has produced a curious corollary: musicians who fall victim to their own legends. Alex Chilton is the king of this ruined landscape, a talented kid who shot to fame on the back of hit singles with the Box Tops in the 1960s, and was later lionized by several generations of taste-making rock poobahs for his work with Big Star, one of the great crash-and-burn flameouts of the power-pop genre. The tale of Chilton’s fall into addiction and dysfunction mirrors that of countless other celebrity heroes brought down by the slings and arrows of their “admirers,” but the part of the story fewer people know about is how Chilton made himself whole again by moving to New Orleans to lose his ambition and find himself in a place where people made music for their neighbors and themselves.

Chilton’s talent was never in question. It was he who questioned the negative vectors of the music industry and the star system, a contradiction obviously built into the cynical name Big Star itself. Chilton wanted to be free of these shackles and play the music he wanted to play, and while it didn’t have the power-pop snazziness of the Big Star sound, his solo projects went deep. The great Hoboken label Bar None Records had released two albums that show this other side of Chilton. One, Songs from Robin Hood Lane, shows his roots in jazz and the Great American Songbook, stretching back to his childhood fascination with trumpeter/vocalist Chet Baker.

Chilton’s talent was never in question. It was he who questioned the negative vectors of the music industry and the star system, a contradiction obviously built into the cynical name Big Star itself. Chilton wanted to be free of these shackles and play the music he wanted to play, and while it didn’t have the power-pop snazziness of the Big Star sound, his solo projects went deep. The great Hoboken label Bar None Records had released two albums that show this other side of Chilton. One, Songs from Robin Hood Lane, shows his roots in jazz and the Great American Songbook, stretching back to his childhood fascination with trumpeter/vocalist Chet Baker.

But it’s the other disc, From Memphis to New Orleans that shows where Chilton was headed later in life. These 1980s recordings, made with several bands over numerous sessions, include his New Orleans-based rhythm section of Rene Coman on bass and Doug Garrison on drums. With a solid roots groove behind him, Chilton plumbs his soul music depths on the Isaac Hayes/David Porter classic “B-A-B-Y,” the Dan Penn/Bobby Emmons chestnut “Nobody’s Fool,” and Willie T’s “Thank You John.” Chilton’s own compositions during this time offer a matter-of-fact view of his circumstances, telling stories like “Lost My Job,” “No Sex,” and “Underclass.” It’s great music by a truly eccentric figure that has not escaped critical notice but has been deeply misunderstood over the years. He was one of those musicians who understood what New Orleans could offer you when every other avenue had been exhausted.