Technical difficulties prevented my daily Jazz Fest report online this weekend. Here’s the weekend in one lengthy post. Thanks for your patience.

Friday

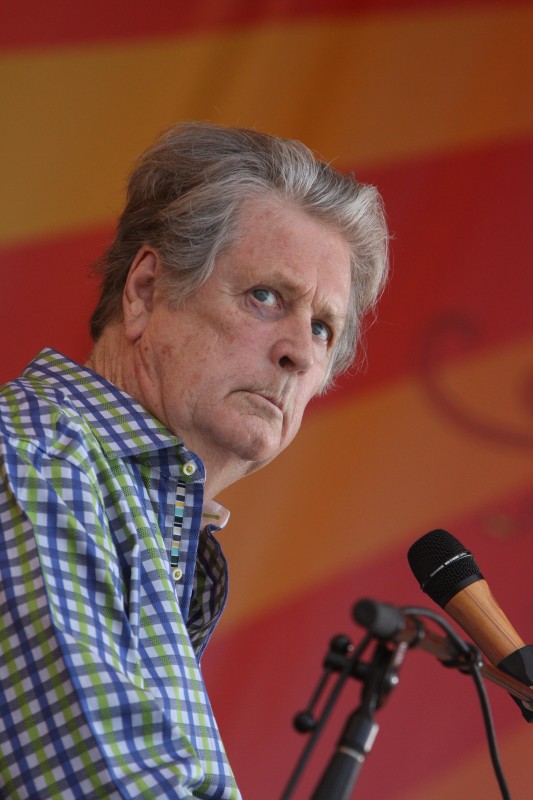

Saturday’s Times-Picayune included a photo from the Beach Boys’ set with only the top of Brian Wilson’s head and his anxious eyes visible behind his white piano. As a picture of fear, it’s beautiful; as news, it’s about 35 years late. Wilson was a catatonic contributor when he first returned to the stage, and that was 10 years after he stopped touring because of a panic attack. In 2012, talk and photos about Wilson’s mental state are documenting a ridiculously old story. Just as the band’s early material presented a vision of California that generations since have wished for, fans hope that each Brian Wilson appearance is going to be the one where he somehow snaps out of it, but by now we know it’s not going to happen and should instead focus on what’s there. Friday he was his usual, fairly inert presence onstage, but his voice was in better shape than it was when he was last at Jazz Fest, and there were some sweet, gently animated touches in his performance of “God Only Knows.”

The show was billed as a “celebration” of the band’s 50 years, but it didn’t feel celebratory, perhaps because nobody onstage looked very happy. The years haven’t been any kinder to Mike Love than they have to Wilson, and a look at the audience that was once randy now looked like lechery tinged with anger. The only interaction between people onstage came when actor John Stamos came out to take the drum throne that he occupied during one of the post-Brian incarnations of the band. Stamos was Love’s guy, unlike the Wondermints’ Mike D’Amico, who has been backing Wilson live in recent years and on this tour. Love did a schticky intro of Stamos, explained theatrically what he wanted him to do in the song—”Be True to Your School”—then made a joke about sleeping with Stamos’ mother the year the song came out. “That’s a ‘yo mama’ joke,” Love proclaimed proudly to end the coarse bit.

The set started with seemingly rote performances of the band’s early classics and a few oddities, including “Then I Kissed Her” and “The Old Cotton Fields Back Home”, but by the middle of the set, the material and performance came together for a beautiful string that included “California Girls,” “Sloop John B,” “Sail On, Sailor,” “Heroes and Villains” and “God Only Knows.” The run ended with the new “That’s Why God Made the Radio”—the sort of oldies-like song that appeared on many of the later Beach Boys album that never sounded classic nor contemporary.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OGke6pnT1d0[/youtube]

I feared the show was going to sound like three guys in front of you singing in front of the songs you know and love because the Wondermints can play and sing the songs the way we want to hear them. Wilson, Love, Al Jardine, Bruce Johnston and David Marks acquitted themselves far better than I expected. The show wasn’t as thrilling as Wilson’s because there was a built-in drama that made its beauty poignancy, but it was as strong a performance as could likely be expected from the Beach Boys 50 years later.

Other notes from Jazz Fest:

– “If you said you wanted to jump off the Eiffel Tower, he’d call someone to help you get there,” Seun Kuti said during his interview on the Alison Miner Music Heritage Stage. “Of course, he’d say, ‘You know you’re going to die, right?'” Kuti was talking about the hands-off parenting style of his father, Afrobeat pioneer Fela. He repeated Fela’s assertion that good African music sounded good without the drums, then demonstrated that playing a song on the tiny stage accompanied only by bass player Justice and Egypt 80’s baritone sax and trumpet.

As funky and compelling as the horns-and-bass combo was, the full 16-piece band (scaled down for the American tour) was ferocious on the Congo Square Stage. Kuti started the show as he starts all of them—with a Fela composition “as a sign of respect.” He dramatized the lyrics to “Zombie,” at points walking theatrically and spastically from imaginary collision to imaginary collision, and the physical dimension added something valuable to the music. Seun’s Afrobeat is as political as Fela’s, and on record there is little sense of pleasure, despite the relentlessly funky grooves. Kuti took obvious pleasure in the extreme physicality of his performance, even using it for comic effect. In his introduction to “The Good Leaf,” he remarked on the injustice in goverments’ anti-marijuana stance. “Mother Nature sends a tsunami, kills hundreds of thousands—not illegal. Mother Nature sends a little plant—” and he finished the sentence with a jumping stomp. On cue, the air filled with pot smoke.

– The confidence David Shaw has developed as the lead vocalist for the Revivalists was obvious and impressive Friday at the Gentilly Stage. This year, there are speakers on the ground in front of the stage, and Shaw regularly performed from them, twice sitting down on them—once with guitarist Zack Feinberg—to perform as casually and informally as if he was on his porch. That he succeeded in making the moment intimate was even more impressive.

– The first act of this year’s Jazz Fest to interrupt my plans was Leyla McCalla, whose set in the Lagniappe Tent was riveting in its self-assured smallness. She played a strummed cello and banjo, and was accompanied by a second banjo and, on occasion, Alfred “Uganda” Roberts on percussion and the Carolina Chocolate Drops’ Rhiannon Giddens on vocals. McCalla is performing with the Carolina Chocolate Drops these days, and like them, she’s exploring old music without making it sound old. Friday, her set leaned heavily on Haitian folk songs, but what was most winning was her artistic confidence—the assurance that the music and performance never needed more than three acoustic instruments. And she was right.

Photos from Friday, April 27 at Jazz Fest

Saturday

This morning, music industry critic Bob Lefsetz wrote about a recent Bruce Springsteen show:

What kind of crazy fucked up world do we live in where the highlight of a Bruce Springsteen show is not only a new song, but one that features rapping?

We don’t go to the Springsteen show to look forward, but back. To when we were thin, our skin was smooth and our hopes and dreams exceeded our losses, when we still had our optimism.

But decades have taken their toll. It’s not that we don’t smile, it’s just that it didn’t work out how we planned. So we go to the Springsteen show to remember, who we were, when music was the most powerful medium, when we felt we could change the world.

Lefsetz then talks about changes in the music business and the world since Springsteen’s heyday before finishing on a more positive note:

So you scrape up a hundred bucks and go to see Bruce Springsteen. Who’s like a traveling preacher of old. And despite all the press, most people don’t care. Just you.

And that’s enough. You just want to go to the show and hang with your brethren, whose names you do not know, but whose lives you’re very familiar with. You had the same experiences, you bought “Born To Run”, you went to the show, it energized you, made you think of the possibilities.

There’s a lot of truth in that, but it was also true Saturday to a lesser degree for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ set at the Acura Stage. His music isn’t as self-consciously a rallying cry or the expression of a conscience, but as the acres of people that jammed the stage made clear, Petty was one of those artists who could be a focal point for that collective moment. He’s demographically perfect for Jazz Fest—started in the ’70s, he believes in the rock ‘n’ roll verities, and he continued to release hits into the ’90s. Generations have first-hand relationships with his music.

With that in mind, all Petty had to do was show up and play the hits and most of the crowd would have been very happy. Many main stage acts have done exactly that, but Petty’s set list reached for album tracks, bluesier songs from 2010’s Mojo, and a garage-rock take on Bo Diddley’s “I’m a Man.” He didn’t neglect the hits, but he refused to be a nostalgia machine and didn’t limit himself to them either.

Petty’s obviously a musical veteran, but the years don’t show in ways that matter. His Florida accent is still very present, and even though he and the Heartbreakers are better players than they once were, it never felt like time and professionalism had worn away anything essential. “Here Comes My Girl” from Damn the Torpedoes still has a slightly awkward hitch as it goes from the pre-chorus to the chorus, and thousands of performances haven’t made the transition easier. As such, the show never felt like memories of rock ‘n’ roll past but for many, like rock ‘n’ roll memories being made.

Elsewhere on the Fair Grounds:

– If Jazz Fest wants to book the Congo Square Stage like it’s on par with Acura and Gentilly, it needs a similar chair policy. The glut of chairs up to rails put there by people waiting for Cee Lo Green brought back bad memories of acrimonious real estate battles at the Acura Stage from years ago. Friends and I waded in to try to see Cheikh Lo and got serious stink eye every time we tried to stop.

– Note to bands: Don’t count down how many songs you have left. It seems like you’re apologizing to us for having to put up with you as you reassure us that you’ll be out of our hair in moments.

– Is there something Pavlovian in the hear-weed/smoke-weed connection? On Friday, Seun Kuti introduced “The Good Leaf” and on cue, there was smoke in the air. Saturday in the Lagniappe Stage, Meschiya Lake sang “Reefer Man” and no sooner had she finished the first line when….

– Empress Hotel sounded great opening the Acura Stage with verses that establish mood before shifting with admirable and almost imperceptible grace into lovely hooks that they weren’t afraid to work for a bit. In early press materials I received on the band, glam rock band Sparks was named as an influence, something I hadn’t heard until Saturday when the big stage PA made the affectations in Micah McKee’s voice clearer. He’s mannered, but not so much that it’s distracting, nor so much that it mutes the emotional impact of a song. He introduced “Search Lights” as being inspired by Al Green, and you can feel his reverie in the “waiting for the sun” passage. You had to wait a moment to hear the soul in the song, though. At first, all I heard was Dark Side of the Moon-era Pink Floyd, which made me wonder if Floyd is in the indie air these days. During the Revivalists’ set Friday, David Shaw sang a couple of extended wordless vocal passages that recalled “The Great Gig in the Sky” (and he did them justice).

– The Soul Rebels performed in the bomb site that was the Congo Square Stage after Cee Lo’s set, and they included their cover of “Enter Sandman”—a song they added to their repertoire for a week of shows in San Francisco opening for Metallica. I had looked forward to seeing them do it since I first saw video of it, but in this context, it seemed like a novelty, and as a friend observed, less funky than everything around it in the set. It certainly paled next to the Earth, Wind & Fire-inspired dance party of “504.”

– “If we weren’t playing, we’d be out there,” Feist said, referring to Tom Petty’s show at the other end of the Fair Grounds. She was wrapping up an adventurous set with “a lullaby”—“Let it Die”, with its melancholy chorus “the saddest part of a broken heart / isn’t the ending so much as the start.” The last half the show didn’t lead inevitably to that moment, though. She rarely went to such a confessional and conventional place, More representative was the percussive “Sealion”, with the backing vocalists including the three-woman group Mountain Man adding percussion in the way they phrased the song’s title in each repetition. It bordered on tribal, over which she added a couple of knotty, distorted guitar solos. It was much heavier than the version on The Reminder and a reminder that there’s far more to her than the lightweight “1-2-3-4”—her introduction to much of America.

– Normally, I grouse about the boomy, cannon-like drum sounds seemingly preferred by Jazz Fest soundmen. I don’t get it since it usually adds murk in the low end, but it was exactly right for Jerome Deupree at the Jeremy Lyons and Members of Morphine set in the Blues Tent. The band’s emphasis on low-end sonics—Dana Colley’s baritone sax and Lyons’ two-string bass—was perfectly suited to the tent, where the roof kept the sound in and the cement floor kept it all alive if not exactly reverberating. I look forward to this band developing a clearer identity—it performs under the name it used at Jazz Fest and as the Ever-Expanding Elastic Waste Band, and it has performed bluesier sets and more Morphine-oriented sets—but it was a perfect matching of space and band and setlist on Saturday.

Photos from Saturday, April 28 at Jazz Fest

Sunday

“In the Gris-Gris days, you scared me,” Bruce Springsteen told Dr. John when the Night Tripper joined him onstage Sunday at Jazz Fest. Dr. John led the E Street Band in a version of Chris Kenner’s “Something You Got,” one of Sunday’s many variations from the setlist Springsteen has been playing on this year’s Wrecking Ball tour. It started fairly conventionally with “Badlands,” “We Take Care of Our Own,” “Out in the Streets” and “Wrecking Ball,” but Springsteen also revisited songs from We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, the songs he played when he first appeared at Jazz Fest in 2006. They’d only practiced them in the trailer before the show, he warned, and the starts were accordingly imprecise, not that anybody cared. “O Mary Don’t You Weep,” “How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live?” and “Pay Me My Money Down” were received as enthusiastically as every other nugget from the Springsteen catalogue, new and old.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gd0HBhaT3kE[/youtube]

The show didn’t quite span the breadth of Springsteen’s career, but it came close, reaching back as far as Born to Run and visiting Darkness on the Edge of Town and The River, the latter for “Out in the Street.” The song seemed a little lightweight sandwiched between the weightier songs from Wrecking Ball, but it also made a subtle point as it dramatized the sort of life and good times that are threatened by the economic forces that haunt the new album. It was one of the few times when Springsteen did anything subtly Sunday, but it was more powerful than his self-conscious evocation of spirits—a thread that ran throughout the show with forced determination. Sometimes he coaxed some drama from it, such as when he asked with ministerial repetition, “Are you missing anybody?” More often, though, it felt heavy-handed and unnecessary.

He was winning the audience even before mentioning spirits through his obvious passion for rock ‘n’ roll and the joy of playing it. He’s a showman, and his gift for decades has been his ability to connect at a human level, even in arenas. On Sunday he left the stage for a riser about 20 feet from the stage, where he finished “Waitin’ on a Sunny Day” with a young man he’d pulled from the crowd. He gave the fan the mic to take over the lead vocals on the chorus. As the guy’s nerves kicked in, he struggled, but Springsteen encouraged him. When Springsteen shouted, “C’mon E Street Band,” the guy reflexively did the same and Springsteen lifted the guy by his waist and held him up in an oddly sweet moment. On his way back to the stage, someone threw Springsteen a hat that he put on and wore back to the stage with equal charm. Moments like that or dancing with the signing women were more powerful than the theatrically slow, mournful interpolation of “When the Saints Go Marching In” into the gospel-tinged “Rocky Ground.”

Springsteen’s ability to connect with his audience is linked to his ability to evoke community, another trait from the earliest days. The E Street Band has always been a large band, and he’s joked with them, mythologized them, and made the sheer number of band members speak. Sunday was no different, though rather than using Miami Steve Van Zandt as his foil, he invited the horn section, including Jake Clemons, Clarence’s nephew, to join him in jaunts to the lip of the stage. Springsteen was part of an onstage community and did everything possible to make it seem like everybody in the crowd was part of it too. During the show-closing “10th Avenue Freeze-Out,” he paused after the line, “When the change was made uptown and the Big Man joined the band” and hugged a sign that someone had made—“New Orleans Loves Clarence”—and orchestrated a prolonged cheer in Clemons’ honor. It furthered the sense of community and was the show at its best.

Other Springsteen thoughts:

– He introduced “Jack of All Trades” with pointed, class-conscious thoughts that referenced the Occupy Movement. Did the people with enough money to buy their way into the VIP trough immediately in front of the stage have enough self-awareness to cringe in that moment?

– While the assembled masses felt community with Bruce, they weren’t that fond of anybody encroaching on their space. At noon, the Acura Stage grounds were fully staked out from the chalk line to the track with people starting to move folding chairs into the drainage trench that serves as a walkway. Some stretched out their tarps to occupy enough space to park an Acura. One group in the standing area had laid down their folding chairs to demarcate their territory by a barrier. The whole land-grab vibe was heinous.

– People who hope that one day Jazz Fest will get a McCartney or U2 should remember this weekend, which likely marked the high end of what Jazz Fest can accommodate without reconfiguring the grounds. It’s not simply that Springsteen and Tom Petty have massive followings; it’s that they’re so big that the small percentage of passionately committed fans can still fill the Acura lawn. Even people who normally wander camped out for Springsteen, and the situation would only be worse with bigger bands.

Elsewhere Sunday:

– At the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Johnny Sansone spoke of how he liked playing the opening slot on the Acura Stage on Sunday—how there are five people there when you walk onstage, and how they become 500 once you start playing and become thousands after that. This year, that was tens of thousands, all there from the first note waiting for Bruce. Fortunately, he was up for it with a band that included Anders Osborne and John Fohl. “Invisible” from The Lord is Waiting and the Devil is Too was so moody that it created a haunted moment on a sunny day.

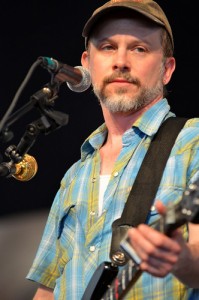

Dave Pirner, Rene Coman, Rick Olivier and Alex McMurray at the Tribute to Alex Chilton at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival Apr. 29, 2012. Photo by Kim Welsh.

– Alex Chilton valued the feel of a performance more than its precision, and it was as if he sent the wind to his tribute at the Gentilly Stage to keep things spontaneous. At one point, Susan Cowsill was helping Dave Pirner with his lyric sheets when the whole sheaf blew off her stand. The wind kept things off-balance but it never derailed the enthusiastic, in-the-right-spirit performance. The Iguanas‘ Rene Coman and Doug Garrison made the tribute one Chilton would enjoy, with songs from his career that Chilton still performed played by people he knew and had some connection to. Players included Alex McMurray, Memphis sax player Jim Spake, Davis Rogan, James Singleton, Vicki Peterson and more. Rick Olivier of the Creole String Beans was particularly entertaining as he sang the songs from Like Flies on Sherbert.

– Hipsters Assemble! Boston’s Debo Band looked irredeemably like a cool kids project, with three horns, two violins, an accordion, guitar, bass and drums playing “Ethiopian groove” music. It worked remarkably well, though, and was often genuinely heavy. A lot of the credit goes to charismatic vocalist Bruck Tesfaye, whose relentless energy and ability to sing while bouncing gave the set just enough authenticity and charm.