Irvin Mayfield was sentenced to 18 months in prison in January 2022, but was released on January 9, 2023, after serving less than a year. Although Mayfield pleaded guilty to diverting $1.3 million in New Orleans Public Library Foundation funding to other accounts for personal use, I continue to wonder why he and his business partner Ronald Markham were the only ones that were held responsible.

The fact that former Mayor Ray Nagin put Mayfield in charge of the New Orleans Public Library system must be examined. I always consider the facts when something seems so bizarre—there’s always an explanation. But over the years no explanation has surfaced, leaving one to make assumptions. Did Ray Nagin use Mayfield to divert money? Mayfield’s troubles seem to have started with his association with Nagin.

Also consider that the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra (NOJO) Board was not charged with any wrongdoing in the court of public opinion. The Chairman of and the NOJO Board would and should have been cognizant of the money being moved from the New Orleans Public Library Foundation (NOPLF) to NOJO, but there was never talk about any real responsibility on the part of the NOJO Board of Directors at the time. It would seem to me that the NOJO Board not only approved accepting the NOPLF money but condoned it, or at the very least they were responsible for the lack of oversight of the financial situation at NOJO. Non-profit board members are responsible for the actions of staff and control fiduciary agreements for the non-profit, whether they are volunteers, or are paid. Moreover, other members of the New Orleans Public Library Foundation Board along with Mayfield and Markham approved giving NOPLF funds to NOJO, but the other members were not charged with any wrongdoing.

Mayfield and Markham were rightfully charged and convicted in the funneling of the NOPLF’s funds to NOJO and for their own personal use, but according to 501c3 (non-profit corporations) the NOJO Board and members of the NOPLF Board (that also included Mayfield and Markham)—were ultimately responsible for any financial wrongdoing. Board members of NOJO and NOPLF came out of this debacle without even a slap on the wrist. Yes, the musicians took the heat as well as prison time. This is not to excuse Mayfield and Markham, but why weren’t the boards of these non-profits held responsible as well?

Mayfield justified moving the money from the NOPLF to the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra by constructing a space in NOJO’s home at the New Orleans Jazz Market for technological assets like touch screens connected to the New York Public Library’s jazz archive, a “digital STEAM” education zone (a visual curriculum connecting science, technology, engineering, art and math), as well as Wi-Fi access in the foyer’s Bolden Bar area—basically, a New Orleans Public Library “branch” located in the Jazz Market. The NOJO Board approved the library branch idea.

The NOJO Board promised to pay back all the money. However, when asked about this, Chairman of the NOJO Board said: “I think there’s no doubt that we’re working on a resolution. This is a very complicated issue. It’s about whether money was spent properly or not. The documents say the money was spent properly.” But the issue was not only how the money was spent, but how the money was obtained. The mayor at the time, Mitch Landrieu, acknowledged this when he said: “The dollars were spent on items that are not clearly library-related… it is important to me that funds privately donated for our library system are invested appropriately. I expect [the Jazz Orchestra] to return all grant funds to the Library Foundation.” The approach, however, from the NOJO Board at the time seems to indicate that since the Jazz Market was devoting “space” for the New Orleans Public Library, the money was spent properly.

The evidence shows that Irvin Mayfield and Ronald Markham are guilty; however, I also believe that Mayfield could have believed he was acting lawfully in his role since he was permitted by the NOJO Board to acquire and spend funds without the requisite board oversight. Mayfield comments regarding this were: “I do not believe that I have violated any law. If I played a role in creating a distraction from NOJO’s mission, I sincerely apologize. I respect all those who may not agree with my past direction or personal judgment, as I recognize their passion as well.”

Mayfield’s Relationship with OffBeat

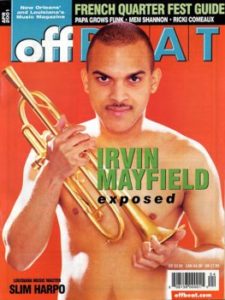

I first met Irvin Mayfield in 2000. We (Jan Ramsey) and I invited Mayfield to dinner at our home. We talked over dinner about OffBeat and Mayfield pointed out that he had not been on the cover. He jokingly said, “What do I have to do to get on the cover, poise nude?” This wasn’t the first-time posing nude on the cover of OffBeat had been proposed. Years earlier, Bernie Cyrus, former director of the Louisiana Music Commission and host of the weekly Cox Cable music program, LTV, proposed the same.

We joked about it, but didn’t take it seriously, until Mayfield followed up with OffBeat indicating he was serious.

In January 2001, he released How Passion Falls, his second CD of original jazz on the Basin Street label. On so many levels, this album represented a quantum leap forward for Mayfield: in the tone, fluidity and expressiveness of his trumpet playing, in his ability as a bandleader, in the top-flight production values, but especially in the breadth and poignancy of his compositions. An OffBeat cover certainly wasn’t out of the question.

I remember walking up to Irvin Mayfield’s apartment building, passing the flourishing art galleries, upscale restaurants and other urbane features of the New Orleans Warehouse District, to talk about an OffBeat cover. I couldn’t help but marvel at how well things were coming together for the 23-year-old musician. That visit was very memorable, because for me, it demonstrated the closeness and even love Mayfield had for his childhood friend and roommate, Ronald Markham. Without exaggeration, Markham and Mayfield were like kids, literally rolling on the floor together, laughing and telling stories. It was a sight to see, and it’s burned in my memory. It gave me a sense that these were real people that shared so much together, and clearly cared deeply for one another.

“Yeah, this is one hell of a year,” Mayfield says as we sat down in his spacious, uncluttered apartment. Any conversation with Mayfield reveals an insatiable intellectual curiosity. As usual, his voice conveys an infectious sort of amused incredulity towards the scope and intensity of all life’s possibilities. “To be able to do two big records like that in a year, it’s amazing,” he continues. “Even pop musicians, how many of them get to do two records a year?”

We scheduled a cover photo shoot, and I followed up with Mayfield. When we got close to the date, I kept asking him if he was actually going to pose nude? Mayfield continued to indicate that that’s what he wanted to do. In a subsequent interview with OffBeat’s Jonathan Tabak, Mayfield explained why he wanted to pose nude. “You know, the thing is I wouldn’t do it if people said I could do it. Jazz covers are always the same thing. You look at Nicholas Payton’s cover, you look at Wynton’s or Ellis’ cover, you look at anybody on the cover, they’ve always got a suit on. So, when I think about a photo shoot, yeah, why shouldn’t I be on the cover naked? Why not? Why can’t I be on edge? My music is on edge, that’s my vibe. Like the controversy over my record cover [for How Passion Falls]. “Why did you use that girl on the cover?” Why not? If it’s sexist, so what, sex is involved in jazz music. It’s okay for the rappers like Mystikal to come out here and say, “Shake it Fast” and all this shit. My music involves just as much of that as everything else does, and I don’t mind showing it. I welcome it. I want people to understand that when you come, you’re going to get sex, but that’s not all you’re going to get. It can be fucking, or it can be making love. Whatever you want, jazz offers it all.”

OffBeat hired local photographer Rick Olivier for the Mayfield photo shoot. When the day came, I remember asking Mayfield if he was really going to get completely undressed for the photo. As it turned out, he removed his shirt and Olivier took the photo. We had to photoshop away the top of his underwear to make it appear that he was completely nude.

In the OffBeat interview, Tabak asked Mayfield if he was trying to use controversy to get attention. “No, I really don’t. Let me tell you something. One of the greatest things about when I first was in Los Hombres [Calientes] was having people come and dance to my music and loving the album. I never felt that before. And there’s nothing like when everybody loves you. Love is the way. I would much rather for everybody to love what I’m doing than saying it ain’t shit, but if that’s what they say, well, fuck ’em. I got to keep moving forward.”

April 2001 OffBeat Cover

In subsequent meetings with Mayfield over the years he expressed his admiration for Wynton Marsalis and what he created. When asked “How much have you consciously modeled yourself after Wynton Marsalis?” Mayfield response: “I haven’t consciously modeled myself after him at all. Only in the sense of work ethic. I don’t have as much of a work ethic as he has. I don’t think anybody does. But I think people assume that if I have a suit on and I’m making a lot of money, and I play the same kind of trumpet he plays, that I’m being like him. Well, obviously you haven’t been around him, because me and him are two completely different types of people. But he is a mentor of mine, and I’m not ashamed to say it. He’s a mentor of mine, just as much as Terence Blanchard is also. Just as much as Clyde Kerr, Leroy Jones, Gregg Stafford or Wendell Brunious is. You know, I talk to all these musicians and ask them questions. I have a great regard for them, and much respect. And I hope to be as great a musician as they are. That’s why they’re my mentors. As far as the amount of press that I’ve gotten so young, see, that looks like Wynton. I didn’t ask for it; people just wrote about me. You know, people assume that I have had this big machine pushing me onto everybody, and this big machine you have to understand wasn’t a big machine two years ago. Shit, it didn’t exist three years ago! This big machine is something that was developed.”

Mayfield had previously lived with Wynton Marsalis for two years. “That was another type of university. I mean, for somebody aspiring to know about art, man, it was just the most amazing experience, to live with an artist like that, somebody who’s into all these different things. He’d be up at three in the morning, and I’d be sitting there, and we’d talk about all kinds of things. Like when he met Ralph Ellison, his experience of first coming to New York, his experiences with Miles Davis. I was hearing those stories, man. And then one of the greatest things being there, I would try to wake up and practice before him. First morning, I woke up at ten. He’s like, “Man, I finished practicing two hours ago.” Woke up the next morning at 8:30 a.m., he’s sitting down eating breakfast. He says, “You see my horn over there is warm.” Woke up the next morning early, like 6:30 a.m., started working on my long tones. Here comes Wynton, walking in the door with some milk, saying, “Man, I already put an hour in.” That’s how he is. Cat sleeps three hours, practices all the time. So, when I talk about Wynton, I’m not talking because I like him or respect him more or I’m more intrigued, it’s that I lived with him. If you live with somebody when you study with them, well, you’re watching what they’re doing, you’re living what’s going on, you know, being at Lincoln Center, going to his rehearsals, watching people come over. I was there when [renowned Cuban-born pianist] Chucho Valdes first met Wynton and gave Wynton an introduction to what makes Latin music Latin, and Afro-Cuban jazz Afro-Cuban jazz. It was a hell of an experience.”

Although Marsalis offered for Mayfield to stay with him as long as he wanted, Mayfield returned to New Orleans. Why? “Well, I was talking to Jason [Marsalis] at the Funky Butt one night, and I said, “Hey, man, I want to put together this thing. Let’s do some Afro-Cuban kind of stuff and do some different things that groove. Let’s do something that will make people say, ‘Wow, we can’t believe these modern jazz musicians are doing this.’”

The success of Los Hombres Calientes gave Mayfield a reason to stay in New Orleans. “My career changed. I mean, I could work in New Orleans and people would come. I could make a living. All of the sudden in the next month and a half, we developed the infrastructure here in New Orleans of Basin Street Records. Jazz went to the forefront. Since then, jazz has been the number one type of record at the Jazz Fest. It changed the whole scheme of what jazz meant in this city. And then I realized I didn’t have to leave. It was unnecessary. I said, ‘Well, I can do this here.’ And it’s what I always wanted to do. The only reason I was leaving is because I felt like I was up against a wall.”

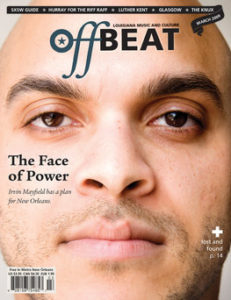

In March 2009, Mayfield was featured for his second OffBeat cover by OffBeat editor John Swenson. “The Face of Power: Irvin Mayfield has a plan for New Orleans,” was the headline. Mayfield was racking up a list of accomplishments. Five albums by Los Hombres Calientes, four solo albums, a duets recording with Ellis Marsalis and an album leading the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra. But as Swenson reports, for all that, Mayfield’s biggest talent may well be as a businessman. He’s just finalized a new recording contract with Harmonia Mundi for the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra, and he’ll host “The Life and Times of Irvin Mayfield,” a one-hour radio talk show on WGSO. He has started a new record label, Poorman Mayfield, and is partnering with the Royal Sonesta in a branding concept he vows will change the nature of Bourbon Street.” Mayfield was especially proud of the Royal Sonesta’s collaboration. Mayfield commented “Our brands match together very well. It’s not just about this room. The Royal Sonesta wants to have the effect of the brand throughout the hotel. They want jazz to be part of the experience and aesthetic of every hotel guest. It won’t be just in the club; it will also be reflected in the rooms, the outside of the hotel and even what we plan to do with Bourbon Street.” The resulting performance room at the Sonesta proved to be very beneficial to all local musicians. Mayfield gave many a local musician an opportunity to play the club. Those musicians were very thankful for what Mayfield did for them, and his generosity has garnered continued support for the trumpeter.

March 2009 OffBeat Cover

It was during this time that Mayfield started to come to the attention of business and political leaders in New Orleans. They include Entergy CEO Dan Packard, who included Mayfield as the first professional musician on the city’s Chamber of Commerce, and Mayor Ray Nagin who appointed Mayfield the Cultural Ambassador of the City of New Orleans. Mayfield held positions at the Champions Group, the New Orleans Museum of Art and on the Louisiana Rebirth Advisory Board as well as on the Bring New Orleans Back Commission Cultural Sub-Committee.

It was Entergy CEO Dan Packard who advised Ray Nagin to appoint Mayfield Chairman of the Board of the New Orleans Library Board of Directors. According to Mayfield, the rationale was that the mayor was looking for someone who wanted to change things at the library. Mayfield’s tenure at the library was controversial. Instead of settling into a traditional role of fundraiser he shook up the staff, forcing out several top librarians. The Times-Picayune published a largely unfavorable piece on Mayfield’s tenure at the library. According to reporter David Hammer, “Often outside the public eye, Mayfield and other board members have cleaned house aggressively—overly so, in the eyes of critics. The four top-ranking librarians and the director of a library support foundation all left as Mayfield, a Grammy nominee whose main gig is directing the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra, conducted a major realignment that made a former mayoral aide who isn’t a professional librarian the system’s top administrator.”

Mayfield responded “Some of the conversation is geared toward ‘Why is he doing that? Why is he taking his time to be Chairman of the Board in the library system and have these people beat him up in the paper? Why is he on the Police and Justice Foundation? Why does a musician care about crime?’ But my answer to all these questions is that we are all citizens in this city and our responsibility is to do what we can to make things better. I challenge people to stop questioning why I’m doing things and start questioning what they’re doing to improve the city. We spend too much time questioning other people’s motives. We’re surviving on the fumes of our culture now, and we’ve got to do better. A child will recover from a trauma, but the issue is how will that child recover? It’s the same thing with the library. The libraries are coming back, but how they’re coming back is the issue. Do we make them what we want them to be, something that responds to the community’s needs, or do we accept the piecemeal structure we had before? We have to integrate music into the library. We have to use it to teach the children about the history of their music, the history of jazz.”

Mayfield spins with the deftness of a master politician, which may be why some people apparently suggested that his next objective should be the mayor’s office. In our old offices at 421 Frenchmen Street, we made a political sign “Mayfield for Mayor” which hung on the wall. When the pandemic hit and OffBeat was forced to move, the sign was given away to Snug Harbor’s Jason Patterson.

John Swenson concluded his cover story on Mayfield: “Irvin Mayfield is a lot of things—musician, bandleader, composer, teacher, cultural contractor, politician—but through it all, he is a man with his eye on the deal, more Donald Trump than Louis Armstrong. His accomplishments and his ambitions are fueled by a shrewd businessman’s sense of

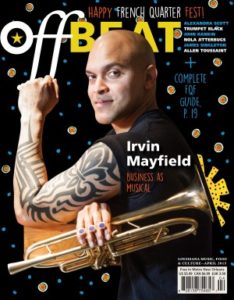

April 2015 OffBeat cover

give and take and an understanding of how timing and salesmanship are essential elements in attaining your goals. Not surprisingly, those traits have made him unpopular in some circles, but like him or not, these are qualities that will serve him well in whatever direction he chooses.

OffBeat’s third Mayfield cover was in April 2015. At this time, the New Orleans Jazz Market had become a reality. Billed as New Orleans Jazz Orchestra’s permanent new home, the 340-seat theater space was poised to elevate the local profile of the orchestra. Meanwhile, its acoustic and conceptual customization for jazz made it a potential magnet for major touring acts. OffBeat contributor Jennifer Odell interviewed Mayfield. Asked about the New Orleans Jazz Market, Mayfield said: “The whole idea is that the Jazz Market is just a physical extension of what we have been doing. The CDs are the musical extension of what we’re doing. Then there’s the book extension, our work is about conveying truth, love and beauty—it’s a lot of stuff, but it’s really the same thing in different ways.”

Markham, once a mechanical engineering major at UNO, spent about 100 hours planning the building’s design. He says he sent the Atlanta, Georgia-based architecture firm Kronberg Wall examples not only of arts centers they liked, but also of arts centers they hated in order to be as clear and detailed as possible about their vision. “The warm tones, that’s Irvin’s dream. The glass, concrete, clean lines, the modernity? That’s me.”

Markham oversaw the nuts and bolts of NOJO’s projects, including the financial aspects of buying and opening the Jazz Market.

When the news struck about Mayfield and Markham’s involvement in moving almost $900,000 from the New Orleans Public Library to the New Orleans Jazz Market and other projects, OffBeat responded editorially. After the editorial (written by Jan Ramsey) I received a phone call from Ronald Markham. Although I have been friends with Markham and Mayfield since they were in their 20s and have personally and professionally supported their efforts to take New Orleans “jazz” to a higher level. But Markham’s phone call unfortunately was very ugly. Markham was obviously upset with the editorial. The editorial, which can be read here, was merely a news story explaining what was going on. But in Markham’s mind it was a betrayal and OffBeat had to be punished in some way. Markham told me that OffBeat Magazine was no longer welcome to be distributed at Irvin Mayfield’s Playhouse in the Royal Sonesta and at the New Orleans Jazz Market. Jan Ramsey indicated that “I’m not surprised by them being upset by criticism—anyone who is criticized in the media is usually upset. I have offered to let M&M respond to our editorial commentary in the July issue in their own words. To date, neither has forwarded a response. The offer is out there. I really would like to understand their side of the story, and why what happened should not have been subject to a critique from OffBeat.”

I sincerely hope that we hear from Mayfield and Markham. They represent a powerful artistic voice, and their contribution to New Orleans music is immeasurable. Mayfield said in an OffBeat interview “If you can imagine New Orleans as a person, I’m just trying to help New Orleans feel good, because if New Orleans feels good, there are a lot more possibilities.” You can’t argue with that, New Orleans presently doesn’t feel very good, hopefully Mayfield can make us feel good again.

Jan Ramsey contributed to this article.