Learning of Alex Chilton’s death during the first night of South by Southwest made the whole enterprise seem a little empty – at least for the night. Almost every rock band here with pop leanings has Chilton or Big Star in its cellular structure whether it knows it or not. As a member of the Box Tops, he sang on the pop/soul hits “The Letter,” “Cry Like a Baby” and “Soul Deep.” Big Star’s three albums present the blueprint for contemporary indie rock, whether in its sweeter, traditional incarnations (#1 Record), it’s more wiry practitioners (Radio City) and its 3 a.m.-of-the-soul artists (Sister Lovers). As a solo artist, he pursued a progressively personal vision with little regard for labels, audiences or sales. That approach produced Like Flies on Sherbet, which wed noise, pop and roots rock by emphasizing the importance of vibe. He made pop archaeology cool in his later years, writing less but digging up obscure pop, R&B and soul classics, seemingly determined to be hip by being unhip; in later years, “Volare” was a staple of his live show. As a producer, he helped Tav Falco’s Panther Burns show that roots music may be best celebrated by its spirit rather than religiously faithful renditions, and his production of the Cramps’ The Songs the Lord Taught Us opened the door to a hundred varieties of goth/macabre stuff.

Learning of Alex Chilton’s death during the first night of South by Southwest made the whole enterprise seem a little empty – at least for the night. Almost every rock band here with pop leanings has Chilton or Big Star in its cellular structure whether it knows it or not. As a member of the Box Tops, he sang on the pop/soul hits “The Letter,” “Cry Like a Baby” and “Soul Deep.” Big Star’s three albums present the blueprint for contemporary indie rock, whether in its sweeter, traditional incarnations (#1 Record), it’s more wiry practitioners (Radio City) and its 3 a.m.-of-the-soul artists (Sister Lovers). As a solo artist, he pursued a progressively personal vision with little regard for labels, audiences or sales. That approach produced Like Flies on Sherbet, which wed noise, pop and roots rock by emphasizing the importance of vibe. He made pop archaeology cool in his later years, writing less but digging up obscure pop, R&B and soul classics, seemingly determined to be hip by being unhip; in later years, “Volare” was a staple of his live show. As a producer, he helped Tav Falco’s Panther Burns show that roots music may be best celebrated by its spirit rather than religiously faithful renditions, and his production of the Cramps’ The Songs the Lord Taught Us opened the door to a hundred varieties of goth/macabre stuff.

It’s hard to write about Chilton and not impose your suppositions about motivations because he was notoriously private. He wasn’t reclusive; I last saw him before Christmas on Frenchmen Street when Alex McMurray and I ran into him, the three of us marveling at three Alexes in the same place at the same time. But as Bruce Eaton documents in Radio City, his entry in the 33 1/3 book series, Chilton was reluctant to participate, even in a book for a well-respected series on one of his great albums.

It’s hard to write about Chilton and not impose your suppositions about motivations because he was notoriously private. He wasn’t reclusive; I last saw him before Christmas on Frenchmen Street when Alex McMurray and I ran into him, the three of us marveling at three Alexes in the same place at the same time. But as Bruce Eaton documents in Radio City, his entry in the 33 1/3 book series, Chilton was reluctant to participate, even in a book for a well-respected series on one of his great albums.

His reluctance let us fill in the blanks – likely as we would fill them in, not as he would. For years, I’ve thought that he was perhaps the perfect example of what the music business can make you. He’s best known for music he made at 16 as the hired voice of the Box Tops, a band that used little of his writing. With Big Star, he made remarkable music, but Stax Records had recently changed its distribution to Columbia, and problems between Stax and Columbia meant that their albums on the Stax-subsidiary Ardent got very poor distribution. He made records he wanted people to hear and no one heard them. After that, he made music that always had “fuck this business” as a subtext. As time has passed, I have come to suspect that  reading; it’s too simple and too generic, based on how people would respond – how I might respond – rather than how he would. It’s very hard to write about Chilton and not speak personally.

reading; it’s too simple and too generic, based on how people would respond – how I might respond – rather than how he would. It’s very hard to write about Chilton and not speak personally.

But Chilton invited that sort of identification. Big Star’s not as revolutionary as its proponents claim, but it’s hard to think of a band that better reflected being young than it did. On all three albums, there’s an undercurrent of confusion and uncertainty, even in the optimistic songs, an undercurrent that would become the dominant thought on Sister Lovers. That spoke more clearly to me than the Beatles or countless singer/songwriters who seemed to have a far clearer handle on the world and their lives then I did then or now. Add to that the hard-to-find nature of Chilton’s recorded output and all the pieces were in place for Chilton to become a cult figure, the beloved of collectors and those who are certain that real music exists at the margins of the mainstream.

The L.A. Times‘ Ann Powers’ reflection on Chilton’s death illustrates this relationship with  Chilton:

Chilton:

Somewhere in a trunk, I have a tattered souvenir from a Big Star store in Memphis, picked up on a pilgrimage to the South that I made when I was barely 21, when I set forth to find some mineral traces of the blues and early rock heritage I’d only read about in books.

What I found on that journey was Alex Chilton. I’d already come to love Big Star’s catalog, introduced to me via the mix tapes my friends and I made for each other as we built our own twisted history of Americana from what the band X once called “the unheard music.” Alex Chilton was a wandering, heretical patriarch of our new religion. Bands like the Replacements and R.E.M. found him inspirational. (Members of one such group, the Posies, would later play with a reformed Big Star.) College radio DJs turned Big Star’s catchy but unkempt songs into the hits they should have been the first time around. The band had been active in the 1970s, but they belonged to us, the kids fighting off the shadow of the Baby Boomers who’d been too dumb to realize how great it was.

We shook our messy hair to Big Star’s strutting rockers, like “In the Street” (the band’s best-known song, thanks to Cheap Trick’s version for “That 70s Show”), and “September Gurls,” party anthems that were like Led Zeppelin hits for the kids who got beaten up by real Zeppelin fans. And we slow danced to Chilton’s ballads, especially those from Big Star’s third album, “Sister Lovers,” made after the band had basically fallen apart. That record remains one of the most lucid expressions of youthful sorrow in the annals of guitar pop, a perfect encapsulation of the pain of that worst, first heartbreak.

We shook our messy hair to Big Star’s strutting rockers, like “In the Street” (the band’s best-known song, thanks to Cheap Trick’s version for “That 70s Show”), and “September Gurls,” party anthems that were like Led Zeppelin hits for the kids who got beaten up by real Zeppelin fans. And we slow danced to Chilton’s ballads, especially those from Big Star’s third album, “Sister Lovers,” made after the band had basically fallen apart. That record remains one of the most lucid expressions of youthful sorrow in the annals of guitar pop, a perfect encapsulation of the pain of that worst, first heartbreak.

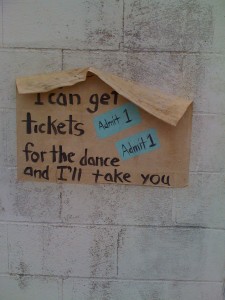

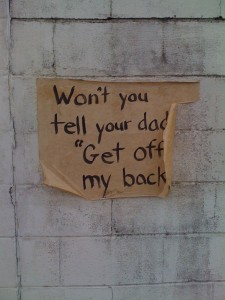

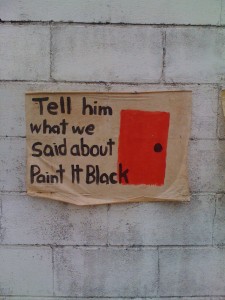

When Jon Dee Graham played the Ogden Museum of Southern Art recently, we connected when he warmed up before the doors opened with Big Star’s “13.” When he finished, I showed him photos of the lyrics to “13” that someone had made into a series of illustrated posters and pasted up on a warehouse on Tchoupitoulas last August (one, “Would you be an outlaw for my love?” is weatherbeaten but still up, on a white wall on the lake side somewhere between Felicity and Race). He was blown away by the posters – the enigma they presented, and the reassurance that “13” still speaks to people more than 30 years after its release and subsequent disappearance. It offers hope that there’s still a long possible shelf life for those  toiling on the margins. When I let Graham know about Chilton’s death, he wrote, “Giants falling right and left; who can even pretend to the size of these immortal dead? Who WANTS to?”

toiling on the margins. When I let Graham know about Chilton’s death, he wrote, “Giants falling right and left; who can even pretend to the size of these immortal dead? Who WANTS to?”

It’s going to be hard to walk around SXSW and not measure bands with that yardstick in mind.