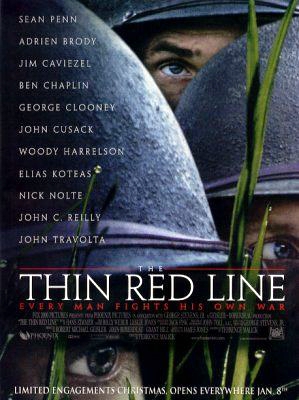

During the 1970’s, writer/director Terrence Malick wrote and directed two small arty films, Badlands starring Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, and Days of Heaven starring Richard Gere and Sam Shepard. Although both films were critically lauded, Malick opted to get out of the system and subsequently disappeared from public view. Until now, two decades after completing only his second film, Malick brings us his new one, The Thin Red Line, which is being touted as one of the best of movies of the year. But don’t believe it for a second.

In 1973, Pauline Kael, respected movie critic of The New Yorker, wrote that “[Badlands is] an intellectualized movie—shrewd and artful, carefully styled to sustain its low-key view of disassociation—but so preconceived that there’s nothing left to respond to. Well, dust off that review because the same thing can be said about The Thin Red Line, a bloated, self-indulgent film that veers frighteningly close to a student film in its imagery and symbolism. And although, a platoon of A-team actors are advertised on the playbill (George Clooney, Woodey Harrelson, John Travolta, John Cusack), the movie only gives us Nick Nolte and Sean Penn in anything that halfway resembles a performance. The others are just window dressing, anachronistic faces popped in to get the movie made. In fact, in a movie that runs nearly three hours (and feels like every minute of it), Clooney appears for all of 90 seconds. Travolta for maybe five minutes. But, that’s not the real drawback here. It’s pacing, plot and performance, or the lack thereof, that relegate The Thin Red Line to shake-your-head status.

In 1973, Pauline Kael, respected movie critic of The New Yorker, wrote that “[Badlands is] an intellectualized movie—shrewd and artful, carefully styled to sustain its low-key view of disassociation—but so preconceived that there’s nothing left to respond to. Well, dust off that review because the same thing can be said about The Thin Red Line, a bloated, self-indulgent film that veers frighteningly close to a student film in its imagery and symbolism. And although, a platoon of A-team actors are advertised on the playbill (George Clooney, Woodey Harrelson, John Travolta, John Cusack), the movie only gives us Nick Nolte and Sean Penn in anything that halfway resembles a performance. The others are just window dressing, anachronistic faces popped in to get the movie made. In fact, in a movie that runs nearly three hours (and feels like every minute of it), Clooney appears for all of 90 seconds. Travolta for maybe five minutes. But, that’s not the real drawback here. It’s pacing, plot and performance, or the lack thereof, that relegate The Thin Red Line to shake-your-head status.

Oh, sure there are moments when Malick’s opus that are gorgeous to look at (John Toll’s cinematography is exquisite) and there’s even a bit of genuine tension when one of the men is completely surrounded by a squad of Japanese dressed in full, palm frond camouflage. There’s just not enough of this sort of thing. Malick’s penchant for disassociation works against the material here, it doesn’t enhance it. A host of characters speak in disembodied voices—clips of mumbling poetry are a Malick trademark—about war and dirt and what it all means rubbing elbows with death. The worst of the bunch is John Savage doing his usual shell-shocked veteran bit that he learned in The Deer Hunter and perfected in later films. Again, Savage’s mindless grunt stands against a white sky and rails against the powers that led him to this awful fate. And, when the characters do speak normally, it’s self-important, pretentious stuff like, “What difference can one man make in all this mess?” Oh, Brother!

Additionally, The Thin Red Line suffers immeasurably when compared to Steven Spielberg’s infinitely more rousing, Saving Private Ryan. I frankly could’ve cared less who lived and who died in Malick’s movie but I certainly wanted Tom Hanks to get home to his wife and her rose bushes. The problem is, I guess, that you can’t go home again. Malick certainly didn’t.

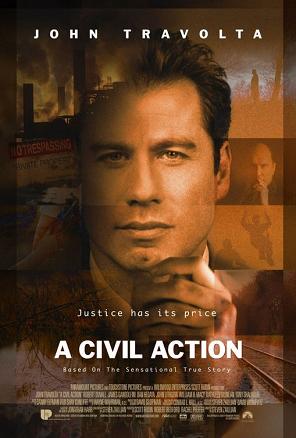

Want a cinematic civics lesson on the cold, hard truths concerning the contemporary legal system? Then look no further than Steve Zaillan’s strange new drama, A Civil Action. Based on the true story of personal injury attorney, Jan Schlichtmann, Zaillan’s film skirts around the issues pertaining to the deaths of a group of youngsters who may, or may not, have been afflicted because of the negligence of two major corporate giants. Schlichtmann is played by John Travolta with the latter’s usual, easy-going charm but the rest of the cast including William H. Macy, John Lithgow, Kathleen Quinlan, Tony Shalhoub is utterly wasted. Only the magnificent Robert Duvall rises above it all to put his signature on the role of Jerome Facher, the quirky attorney for one of the corporations. Duvall does amazing things with an insignificant throw-away line such as, “Do you have silver fillings in your teeth.” Or verbally sparring with Schlichtmann on the dumping site when he says, “Pretty soon you’ll be digging for quarters in the seats of that little black sports car of yours.” This film would have been a thousand times better if we had followed it from Facher’s viewpoint but, alas, that isn’t the case.

Want a cinematic civics lesson on the cold, hard truths concerning the contemporary legal system? Then look no further than Steve Zaillan’s strange new drama, A Civil Action. Based on the true story of personal injury attorney, Jan Schlichtmann, Zaillan’s film skirts around the issues pertaining to the deaths of a group of youngsters who may, or may not, have been afflicted because of the negligence of two major corporate giants. Schlichtmann is played by John Travolta with the latter’s usual, easy-going charm but the rest of the cast including William H. Macy, John Lithgow, Kathleen Quinlan, Tony Shalhoub is utterly wasted. Only the magnificent Robert Duvall rises above it all to put his signature on the role of Jerome Facher, the quirky attorney for one of the corporations. Duvall does amazing things with an insignificant throw-away line such as, “Do you have silver fillings in your teeth.” Or verbally sparring with Schlichtmann on the dumping site when he says, “Pretty soon you’ll be digging for quarters in the seats of that little black sports car of yours.” This film would have been a thousand times better if we had followed it from Facher’s viewpoint but, alas, that isn’t the case.

Zallian, a subtle filmmaker for sure, showed he was much better than this with his emotionally touching. Searching for Bobby Fisher, which he wrote and directed. I mean this is the guy who won the Oscar for adapting Schindler’s List, so he knows a thing or two about getting to the core of the material. But here, he stands back and lets the full measure of the hollow victories take their toll. The problem is: Does someone want to spend their money and two hours watching a movie that never gets into the middle of the fray? It’s like watching a courtroom drama directed by a European director (you can almost hear the clock ticking). While the verdict here is somewhat important, it’s more about the process —how did we get to this point?— than anything else. This movie isn’t about truth, it’s about a court of law and how it works. For those that are interested in legal wrangling, A Civil Action sets up nicely. But, for those that don’t, it doesn’t proceed accordingly.