In his native Sweden, Jonas Bernholm is known as Mr. R&B. A music researcher, writer and record label owner, Bernholm became enraptured with American rhythm-and-blues and rock and roll music in the late 1950s. He began writing about music in the late 1960s, publishing much of his work in the Swedish blues magazine Jefferson. In 1976, he launched the first of his many reissue record labels.

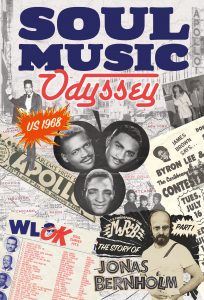

On June 9, 1968, the 21-year-old Bernholm arrived in New York City, the point of the departure for his 81-day music pilgrimage to 10 American cities—New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Memphis, Miami, Houston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Detroit and New Orleans. He frequented music venues, record companies, recording studios, radio stations and musicians’ homes. The detailed notes he made are the basis for his extraordinary memoir, Soul Music Odyssey: U.S. 1968.

Jonas Bernholm. Photo courtesy of Jonas Bernholm

Despite trips to larger cities that produced more hit records, Bernholm’s eight days in New Orleans were the apogee of his odyssey. In the summer of 1968, he writes, many of the city’s past, present and future music stars were all performing in close proximity on Bourbon Street.

“This must be the most music-filled street in the U.S.A.,” Bernholm notes in the book’s 64-page New Orleans chapter. “Frankie Ford resided at the Backstage while Roosevelt Skyes and Smilin’ Joe [Cousin Joe] worked back-to-back at Ye Old Tavern of the Court of Two Sisters. Art Neville & the Neville Sounds could be seen at the Ivanhoe piano bar and Benny Spellman in the Dream Room. All this in just a few hundred meters, and I had not counted the traditional jazz and other musical attractions.

Bernholm’s music reviews and interviews present rare coverage of the late ’60s New Orleans music scene. His photos capture a long-vanished world. One photo depicts a solemn Huey “Piano” Smith seated at his electric piano in his apartment on 7th Street. Other photos capture Curley Moore and producer Marshall Sehorn pouring over a musical score at an upright piano in Sea-Saint Studio; Aaron Neville in a Sea-Saint office; Eddie Bo in Cosimo Matassa’s unglamorous third studio location; and Fats Domino, Irma Thomas, Allen Toussaint in performance.

A brief postscript to Bernholm’s 1968 and ’69 material includes insightful paragraphs about singer-turned manager Joe Jones and the music business in New Orleans.

“Without a doubt, Joe was the nastiest person in the record business I encountered,” Bernholm writes. “He personified the worst of New Orleans and its record industry—the promises, the threats, paranoia, selfishness, back-stabbing and greed, etc. That’s probably the reason why New Orleans has not become America’s musical capital despite having all of the prerequisites there. And also, why I did not release as many R&B reissues from New Orleans as I planned. It was difficult to get things done there.”

The Smithsonian Institution has 26,000 of the records Bernholm collected in its collection. He’s the subject of a documentary film as well as a biography by Jan Kotschack, Resan Mot Rockens Rotter. Supporting material for Soul Music Odyssey: U.S. 1968 is in the Jonas Bernholm Rhythm and Blues Collection, 1976-1991, at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

Following the publication of Soul Music Odyssey: U.S. 1968, Bernholm answered questions about his life in music for OffBeat.

You visited 10 U.S. cities, including the major music cities New York, Chicago, Memphis and Detroit. How important a stop was New Orleans to you?

It was the high point. Fats Domino was on Bourbon Street, as was Clarence “Frogman” Henry. Irma Thomas was great. The visits to the Camp Street Recording Studio were fine, too, although I didn’t realize the historical significance of it being Cosimo Matassa’s studio. My visits to the Sansu Records office (at Sea-Saint Studio) were rewarding also, even though Allen Toussaint didn’t understand what I was looking for. Marshall Sehorn was more of a music fan and understood me.

When you found many recording stars performing on Bourbon Street, did you think you’d struck gold?

It was great listening and talking to Roosevelt Sykes, one of the nicest blues artists I have ever met. Fats Domino was not so happy, though. I guess he had to perform on Bourbon Street because of gambling debts or something similar. But he did a fine show, of course. Art Neville was also very nice. His Art Neville and the Neville Sounds group was really the Meters being created. It was great going to Bourbon Street to see the great artists there. It was similar to Beale Street in Memphis and Auburn Avenue in Atlanta.

In New Orleans, were you surprised that former major stars were performing in small venues? Likewise, some of the artists’ living conditions weren’t so good.

That was strange. I was also disappointed that Frankie Ford tried to be a Las Vegas performer after he had made such a great recording of “Sea Cruise.” I consider Huey Smith a musical genius and wish that Bobby Marchan [former singer with Smith’s group, the Clowns] had been given “Sea Cruise.” Frankie Ford is great, but Bobby Marchan would have been fantastic.

During your 1968 trip to those 10 U.S. cities, what were some other surprises?

I was surprised that many of my heroes were no longer appreciated. Many were clinically depressed, like some of the artists I met in Chicago. Aaron Neville and Huey Smith were quite unhappy, too. They told me all about the record business. It opened my eyes.

Ruth Brown told me that, when she performed at the Hippodrome in Memphis, Elvis Presley was waiting outside the artists’ entrance, asking for help to get into the show. White people were not allowed there. So, Ruth brought Elvis in, and he saw the show from behind the stage. Elvis inspires me. He had a true interest in rhythm-and-blues and was also often the only one visiting the same type of places as I did. On Sunday nights he visited Dr. William Herbert Brewster’s church in Memphis, when they did gospel radio broadcasts.

You mention in your book’s introduction that the 1967 Stax-Volt tour came to Sweden. It made a big impression on you.

They did one show in Stockholm. After Sam and Dave finished their set with “Hold On, I’m Coming” there was a long standing ovation. We all stood up for 10, 15 minutes, screaming while the orchestra played riffs from “Hold On.” For us it was a religious experience, but I was in a trance for weeks and couldn’t think of anything else. And then I realized that the recordings of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf were made 10, 15 years earlier, but the Stax stuff was current. I made up my mind to go to the U.S.A.