Everyone has dropped their phone. The all-too-familiar sound to some of us is like a modern version of putting a phone on a hook or hearing a scratch on a recording—sounds we’d recognize anywhere. Musician Emily McWilliams, a.k.a. Silver Godling, has taken these mundane sounds and has reinvented them into a modern form of music therapy.

The familiar clatter caused by dropping a phone on a piano bench is transformed into a gurgling sound like someone sucking the last bit of a frozen drink out of a straw. Using some post-recording editing tricks, Silver Godling takes it a step further, all but abandoning the sound’s origin by finally creating a squishy sound like Jell-O falling down some stairs.

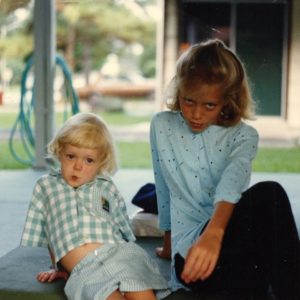

Emily and her older sister Jenni McWilliams together as kids. Emily’s partner and vocalist for local metal band Thou, used this photo as the album cover for Inconsolable.

Clatter, slurp, squish. It’s nasty—distracting even. But with it, she composes a window into her emotional life. We’re positioned to see the room she plays her home piano in, curtains drawn, the warm sun barely brightening the space with a golden tint.

As she plays, the piano emotes complex and vulnerable emotions of love, nostalgia and yearning before inevitably unraveling. Then harsh metallic synths echo slowly as the sounds begin to mask the comfortable, soft, gooey slurps and suddenly—it all stops. All that’s left is the harsh ringing synths. Discomfort.

This is the first track of Silver Godling’s latest album Jenni, an album full of these common sounds transmogrified into a tribute to her 47-year-old sister Jenni Lynn McWilliams, who died on September 7, 2022, after a 30-month battle with metastatic breast cancer. Silver Godling’s real name is Emily McWilliams and as herself, she recorded it all to find catharsis from grief in the days after her sister’s passing.

“It was just therapeutic during that time. I really did love the detailed, sometimes monotonous work of building sounds and textures,” said McWilliams, “I would find a sound—whether it’s laying my phone down or my mom laughing in the next room—and I would isolate the track to mess with it. Slow it down. Reverse it, whatever.”

Half-recorded in her sister’s home in Pennsylvania and half-recorded at her home in New Orleans, McWilliams had no intention of using the recordings for a public release but rather thought it would be to “self-soothe.”

Trying to Feel

In a multimedia tribute to her sister, McWilliams wrote, “Born in New Orleans just like me, she ended up living in south-central Pennsylvania where much of my extended family lives. My dad and I arrived in Pennsylvania just hours after she took her last breaths in my mother’s arms. I spent the next seven days with my family, planning her funeral, staying in her home with her son and his father, and trying to feel whatever I felt.”

Classically trained, McWilliams started learning to play the piano at seven years old and began writing her own music in high school. Despite her training, she did not release or perform her music publicly beyond the occasional open mic or recital. Her anxiety and distaste for performing live would pass as she took extracurricular music classes in college. However, she wouldn’t start a formal solo project until Silver Godling.

In 2014, McWilliams created Silver Godling with Michael Moises for Not Enough Fest, a woman and queer-positive music festival featuring only new bands and artists. “When I put together the official project for Not Enough Fest, I had trouble figuring out what to call it. Bryan (my partner) actually came up with the name, and I said, ‘I like that!’ It felt right. I realized I liked how both silver [the metal, considered inferior to gold] and godlings are diminutive, and whereas I love to celebrate what humans are capable of achieving, I also—perhaps even more strongly—like to remember that we are infinitesimal and only a part of the world and nature.”

In the project’s early days, she described it as “songs I already had written, and we just added guitar.” But since the pandemic, she has made Silver Godling her focus with an emphasis on every sound being created by her or her piano.

Every morning following her sister’s death, McWilliams would play on the little Young Chang upright piano in the side room of her sister’s home. There she created the first five piano pieces that would be the basis for Jenni. She would record more after returning home to New Orleans, adding an additional five tracks to the album.

“I pulled all of that [the voice memos] into Logic Pro and I would find a noise in each of them,” McWilliams said about the textures she would build from recordings. “Each piece is named after the sound.”

A phone click as an isolated note, an oatmeal spoon, her mother laughing, a shifting seat—these are some of the sounds that built the intimate window into McWilliams’ musical grieving process.

“It all happened so fast,” she said.

The prognosis was always terminal. Diagnosed in Spring 2020, Jenni had only a two to five-year life expectancy. Following the diagnosis, McWilliams wrote “Naming Time.”

“I was trying to figure out where I was and how I felt about this idea of her simultaneous presence and absence,” she said.

Jenni’s decline still caught everyone by surprise. McWilliams had begun planning some sort of tribute, perhaps by recording some of Jenni’s favorite songs. But then she got the call to fly to Pennsylvania.

McWilliams and Jenni grew up together in New Orleans. Being 11 years apart, the most vivid memories McWilliams has with her sister come from childhood and her early teens when Jenni moved back home from college for a time. Despite not living together very long, the siblings were always close.

Whenever McWilliams would visit Pennsylvania, she would stay at Jenni’s house. While going through Jenni’s things and old family photo books following her death, she discovered new things about her sister.

A screenshot of the photo collage music video Emily McWilliams created with Mitch Wells of local metal band Thou.

“I didn’t realize the extent to which Jenni loved flowers until after she was gone,” McWilliams wrote, “I brought home most of her floral jewelry with me as well as a carnation from the wreath that surrounded her urn. Even amidst chaos, she loved beauty.”

The flowers inspired her to create a video collage of the old family photos set upon a flower bed in New Orleans’ City Park. McWilliams has grown fond of the multimedia approach some artists use in their work and aimed to do the same with her work, releasing a documentary-style video and an exhibit on her website. She turned all of this around for the two-month anniversary of her sister’s death.

“It was very hard. The process of making it was not, but to release it—I did not anticipate how hard it was going to be,” McWilliams said, reflecting on the quick turnaround and the whirlwind of emotions that led to her feeling more aggravated and sadder when it was all over.

“A person has to face things, but getting absorbed by those things…,” she explained, “I’m someone who has dealt with depression since I was young. I’m familiar with the feeling of sinking into it. I know that feeling of, ‘Oh shit, I’m not going to get out of this.’ I think the way I’ve been experiencing grief is similar to how I’ve dealt with difficult things in my life.”

Through years of therapy, McWilliams learned that if she allowed herself to feel whatever strong, overwhelming emotion threatened to pull her down, then she would find balance and be able to extricate the feeling. “Letting [the feeling] breathe, not padding those feelings down,” McWilliams summarized, “Allowing them to come out, makes it a little less severe.”

Therapy taught McWilliams how to use tools to cope. One tool she was well-suited to use was music.

A Tool If You Can Reach It

Hanging on the wall in McWilliams’ home is a six-string acoustic guitar. She says she can’t play it well but does anyway. When the 30 years of training as a classical piano player gets in the way, the guitar is like starting over. She can let go.

“With my classical background, music is all brainy and intellectual, right?” she said, “But with music therapy, you learn to turn your technical brain off and allow the emotional brain to come through.”

Like the voice memos for Jenni, she could just play. She would find her voice in the keys. Later she’d soothe herself by listening to the recordings. And when that stopped working, she’d engage the technical part of her brain and fiddle with sounds in electronic programs.

Whether she was aware or not, McWilliams was practicing at least three of the four major tenets of music therapy.

According to Jeremy Love, a New Orleans music therapist who has practiced professionally for over 10 years, music therapy can be summarized into four domains: creative, recreative, receptive and improvisation.

Emily McWilliams’ hands as she performs Jenni live at Gasa Gasa opening for Lingua Ignota. Photo by Dalton Spangler.

The creative is the process of writing music, a practice with benefits many musicians know well. It allows the product, whether it be a song or something else, to become the vessel for emotions, memories and trauma.

Although McWilliams clearly used this practice by making Jenni, she also found relief in the electronic distortions of acoustic sounds like the phone click and her mother laughing.

Karaoke lovers know the catharsis of the recreative domain, recreating existing music or learning a new song as a form of expression. It can also be creating a playlist or a mixtape. The process of taking music and creating your own story or meaning out of it through the construction of a playlist can have a beneficial effect.

On Jenni, McWilliams recreated the story of her relationship with her sister by including and reworking songs she’d written about her in the past.

Receptive is listening to music. Perhaps the most common form of music therapy, the effects that listening to music has on the mind and body is well documented but not fully understood. Listening to music can awaken the unconscious in those with Alzheimer’s or be used to manage pain by reducing the heart rate.

After recording the voice memos in Jenni’s home, McWilliams would listen to the recordings to self-soothe as well, a reminder of the emotions behind every piece.

Improvisation, Love’s personal favorite, is the practice of playing music but with the fundamental difference of simply expressing rather than creating. It doesn’t matter if you know how to play or if anything is being written down or recorded. It’s simply just playing.

Much like how McWilliams spent her mornings following her sister’s passing, she allowed the keys to express her feelings in those moments.

These are all practices people as music fans and musicians know intimately. The power of music is what draws most of us to music in the first place. Love calls it universally human.

“Ultimately, we’re all the same anyway. I find I can do the same interventions with children who have Down syndrome or autism with 40-year-olds who served in Bush’s war,” he said, “We’re all human. We all have a biochemical, emotional, cognitive reaction to melody just the same as someone with PTSD or a traumatic brain injury. It may be specific to their experience, but the stimulant is still the same and internal mechanisms are the same.”

Love started learning how to play string instruments when he was eight years old and continued to pursue a career in classical guitar. He rigorously studied the instrument but, as he put it, “life happened” and his dreams were left on hold. He moved to New Orleans and paid his way working in construction as a superintendent for nearly 20 years before he eventually burnt out. That’s when he decided to enroll in Loyola’s music therapy program.

“I loved the idea that through music, I could effect change and help people in a meaningful way through something that I found meaningful to me,” Love explained.

Unlike McWilliams and Love, who can use music therapy for themselves as able adults with 30 plus years of music experience, many do not have the resources, knowledge and experience to effectively treat themselves.

Since earning his certification, Love has actively tried to bring more music therapy to the state of Louisiana by joining the Louisiana Music Therapy Task Force. Despite mounting scientific evidence, music therapy is not officially recognized by the state government, which limits funding and ultimately limits access to potentially beneficial treatment.

According to Love, people seeking music therapy in New Orleans cannot use third-party reimbursements which means health insurance companies can’t provide a co-pay for music therapy services. Naturally, most families cannot afford music therapy without insurance.

The Children’s Choice Waiver, passed in Louisiana in 2001, allows children and their families to receive supplemental support with various services like music therapy. Despite families supposedly having the choice for their treatment, Love says that having mechanisms in place to actually help families do not exist because of the state’s lack of official recognition.

“It’s representative of the dysfunctionality of politics here,” Love chuckles, “No one, as far as I’m aware, has been successful in actually activating the resources.”

Over a dozen states in the U.S. have begun recognizing music therapy as a legitimate form of mental health treatment. Even neighboring states like Texas and Georgia have introduced or have begun planning official recognition for music therapy. So, the question becomes, why hasn’t Louisiana done the same?

Mission of a Music Therapist

“Grief is an interesting phenomenon because it isn’t just about death. You can grieve anything,” explained Love.

Music therapy is sometimes used in hospice to help the dying and their families cope with the transition. One form of treatment Love has used to treat grief is by creating a “life review,” a kind of playlist that tells your life story through a music library of songs, albums and artists that define years of a person’s life. “They can reflect upon their history through music to work out some kind of closure. If you’re getting ready to transition, it would be healing and you can create a product like a CD of 20 or 40 songs that represent your life story in music,” Love explained, “It’s something you can leave for your family and your children.”

When working with clients, Love has found that the best course of action is to avoid a “behavioral” approach—meaning viewing certain behaviors as problems and eliminating them. Better is to cater to the specific needs of the individual as the best course of action.

“As a therapist, you have a toolkit and you improvise with what fits best at the moment to fit the client’s needs,” Love explained, “When you think about PTSD—which is a form of grief—you can retrigger or retraumatize, so I would call grief work advanced practice.”

Love warns that although a person could theoretically provide themselves with music therapy, the certified music therapist knows to accountably provide that assistance to someone else through knowledge and experience. Like most therapists, a certified music therapist acts as a guide for those wanting to help themselves. He brings up Kenneth Bruscia’s book Defining Music Therapy, which he calls the Bible for freshman music therapy students.

“[Bruscia] says music therapy basically is using music to help effect change in non-musical ways,” Love recalls, “So music is the catalyst. The change isn’t music. You’re not creating music; that’s not the goal of a music therapist. The goal is to help the client create the change.”

‘Wake’ as a Noun

“As with any loss, you still feel them in your life but they’re not there,” McWilliams said.

At Jenni’s funeral, McWilliams cried a lot. The commemoration of her life and her death made it more real.

“You think about a funeral. Some people are crying and screaming and feeling all the things. But some people are dry-eyed and sitting there. Maybe they’re in shock or maybe they’ll never feel those strong emotions until years later,” muses McWilliams, “That’s just how it is with grief.”

Like a funeral, McWilliams’s album collects moments of her sister’s life to honor her death and it eases one into a world without that person.

For the first time ever, McWilliams doesn’t know or care what others will think about her music. But after releasing Jenni, McWilliams was surprised to receive messages from friends and strangers alike that her music was helping them through their own grief.

“It was not an intention but a byproduct of putting it out in the world,” McWilliams reflects, “It’s very touching that it’s providing relief for people like it provided for me, which was the whole process— the whole reason why this exists.”

To purchase a digital copy of Jenni, visit this link.