Long before Scott Billington became a staff member at Rounder Records in 1976 and ultimately became the label’s successful producer, he had a passion for music, especially the blues, its purveyors and their recordings. That deep love can be heard on the records he produced for such inspired artists as vocalists Irma Thomas and Johnny Adams, the Dirty Dozen Brass Band and more. Their careers rose due in part to his attentiveness to detail and big open ears.

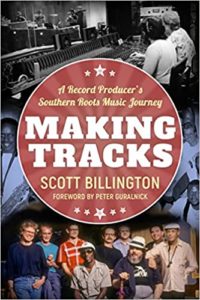

It can also be realized in his new book, the excellent Making Tracks: A Record Producer’s Southern Roots Music Journey. Billington, who occasionally sat in on harmonica for some sessions, proves himself a master storyteller in relaying firsthand accounts of meeting and working in the studio with some of the world’s greatest talents, offering insights into their musicianship and personalities. But musical genius can be accompanied with serious idiosyncrasies that might play havoc with a recording session. Through Billington’s bios on such icons as pianist, vocalist and composer James Booker and soul man Solomon Burke, he obviously found the patience to work through the dilemmas. His aim was simply to make the artists sound their best.

It can also be realized in his new book, the excellent Making Tracks: A Record Producer’s Southern Roots Music Journey. Billington, who occasionally sat in on harmonica for some sessions, proves himself a master storyteller in relaying firsthand accounts of meeting and working in the studio with some of the world’s greatest talents, offering insights into their musicianship and personalities. But musical genius can be accompanied with serious idiosyncrasies that might play havoc with a recording session. Through Billington’s bios on such icons as pianist, vocalist and composer James Booker and soul man Solomon Burke, he obviously found the patience to work through the dilemmas. His aim was simply to make the artists sound their best.

Billington quotes saxophonist Alvin “Red” Tyler, whose rich horn he often utilized, speaking about Booker: “It’s like trying to capture the wind.” It’s those kinds of details that constantly brighten the author’s tales as well as his explanations on how he came to choose just the right musicians for each individual performer’s recording. Relating his experiences in various studios, the author reminds readers of who was there as well as their contributions. Some were “go-to” guys like the rhythm team of drummer Johnny Vidacovich and bassist James Singleton, who backed up Booker (among others) and are now most often renowned on the modern jazz scene. The late drummer Herman Ernest seems to have saved the day with his solid backbeat and humor while working with Solomon Burke. The wonderful Wardell Quezergue often got the call as an arranger. Given an assignment, he’d sit down at a card table, not a piano, and write down all the charts.

One can almost hear the shudders of the “cheap” rental car as Billington hit 80 mph in an effort to keep up with the zydeco giant Beau Jocque’s van and trailer heading down the two-lane causeway that crosses the Atchafalaya Basin. “I was beginning to learn that nothing could be fast enough or big enough for Beau Jocque—his cars, his sound system or his dreams,” Billington writes. In this chapter, the author offers a biographical snapshot of the artist, who was born Andrus Espre, by visiting him in his hometown of Duralde, Louisiana, being introduced to him by Kermon Richard, the owner of the famous dance hall, Richard’s Club, and, sadly, the tragedies that befell him.

Billington’s descriptions of the zydeco dance halls, where the floors shook with the power of the music and two-stepping feet, puts one right there, feeling the heat and humidity and smelling the smoke and beer.

It makes sense to read the chapters of Beau Jocque and Boozoo Chavis back-to-back as their names will forever be linked, despite their stylistic differences, due to the battles between the two zydeco stalwarts at Rock ’n’ Bowl to determine who was top dog. “In reality, they were friends,” Billington explains.

Billington’s travels took him to Chavis’ Dog Hill home on the outskirts of Lake Charles, Louisiana, where the accordionist, vocalist and composer raised racehorses. “He was a fireplug of a man,” Billington offers and then recalls a recording session at Dog Hill that included a barbecue. “It appeared that half the chickens in Lake Charles had given their lives for the occasion.”

Each of the 13 chapters on the individual artists that include Sleepy LaBeef, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Buckwheat Zydeco, Nathan and the Zydeco Cha Chas, Ruth Brown, Charlie Rich and Bobby Rush, as well as the above-mentioned musicians, hold its own appeal and special moments. In 1982 Gatemouth, the master guitarist, violinist, vocalist and composer, won his first Grammy for the album Alright Again! that was also the first Grammy award for Rounder Records and Billington as producer. Others who won their first Grammy with Billington at the helm include Irma Thomas for After the Rain and Bobby Rush for the hilariously titled Porcupine Meat. Released on Rounder in 2016, it topped the Best Traditional Blues category and was Billington’s last album as staff producer for the label. At the end of each of these sections are albums chosen by Billington under the heading of “Recommended Listening” with a complete discography following more generalized chapters—Zydeco, Rhythm and Blues—that includes guitarist and vocalist Walter “Wolfman” Washington and keyboardist and vocalist Davell Crawford, Tangle Eye, Rounder Records and Afterword.

It doesn’t take a great knowledge about the technical aspects of producing an album to understand Billington’s mindset in the studio. The specialized jargon is kept to a minimum as the focus is most often on the “star” and the energy and soulfulness of the sessions. While New Orleanians, folks from Southwest Louisiana and fans who are familiar with these artists will, perhaps, be the most appreciative of hearing more about these musicians and their recordings, the stories themselves can stand alone as interesting vignettes on music, people, environs and the music business.

Making Tracks: A Record Producer’s Southern Roots Music Journey warmly invites a reader along on a winding road less traveled with all of its bumps, as well as its cruisin’ pleasures. Like most journeys, it’s the people one meets along the way that really makes the trip memorable.