During his more than 40 years as a record producer, Massachusetts native Scott Billington guided sessions for dozens of great roots music artists, many of them from New Orleans and southwest Louisiana. The producer’s 157 albums include recordings by Irma Thomas, Johnny Adams, James Booker, Buckwheat Zydeco, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Ruth Brown, Alvin “Red” Tyler and, more recently, Bobby Rush and Samantha Fish.

“It’s hard to believe that all of that actually happened,” the three-time Grammy winner said. “When I was in the middle of it, it was happening really fast. There were times when I was making eight, nine, ten records a year. One thing led to another, starting with that Gatemouth Brown session in Bogalusa in 1981.”

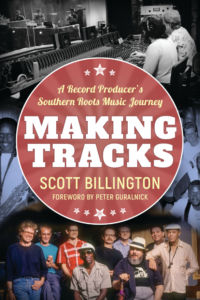

Billington chronicles his musical life in Making Tracks: A Record Producer’s Southern Roots Music Journey. After a foreword by music journalist Peter Guralnick and Billington’s opening chapter about his early years in music, the book concentrates on the artists and the sessions he produced for them.

Billington chronicles his musical life in Making Tracks: A Record Producer’s Southern Roots Music Journey. After a foreword by music journalist Peter Guralnick and Billington’s opening chapter about his early years in music, the book concentrates on the artists and the sessions he produced for them.

Learning on the job, Billington brought his love for music, organizational skills and a personality conducive to creativity to the studio. Even so, he feels lucky to have been in the presence of so many exceptional artists and players. Often, they were his teachers.

“The relative success of one project led to another,” he said. “And I got better at the psychology of running a recording session and figuring out what would cause each artist to bring their best to the studio. No matter how much preparation I did, it was still unpredictable, but it worked and, in many ways, continues to work.”

Because he often produced recordings for Louisiana artists, Billington traveled frequently between his home in Massachusetts and Rounder Records’ apartment in New Orleans. He came to consider the apartment, which was located in the same building as the New Orleans label Black Top Records, his second home.

Since his marriage in 2013 to the New Orleans-based children’s entertainer and author, Johnette Downing, Billington spends most of his time in Louisiana. He’s also a supporting player for Downing, joining her on stage with this harmonica.

After Billington published a story about classic soul singer Solomon Burke in 2020, Downing urged him to write a book containing stories about other artists he produced.

“She really stayed with me, and the pandemic was the perfect opportunity to take time to write,” he said.

Heeding his wife’s advice, Billington began by writing a sample chapter about Johnny Adams, the versatile New Orleans vocalist with whom he made 10 albums, the most he’s recorded with any artist other than Irma Thomas. Aware of the University Press of Mississippi’s American Made Music Series, Billington submitted the Adams chapter and his previously published Burke story to the Jackson-based publisher.

“Once Craig Gill said, ‘Let’s do it,’ I had to finish the book,” Billington said of the University Press of Mississippi director’s support for the project.

Billington dedicates Making Tracks to his wife: “For Johnette, who brought the music home.” Holding a physical copy of his first book feels different from holding copies of the vinyl albums and CDs he’s produced.

“Not that the records haven’t been personal to me, but the book is much more personal,” he said of the stories that reveal the rewards and disappointments that came when he collaborated with such challenging characters as Booker, Burke and Charlie Rich.

Billington completed Making Tracks in merely a year. Having previously written publicity material for Rounder Records, including artist bios and press releases, he brought writing experience to the book. And about 15 years ago, the producer sharpened his prose by taking writing courses from the Harvard Extension School. All the while, four decades of working with wonderful artists and characters gave him rich source material.

Billington sees the 1980s and ’90s—years when Rounder Records and the Scott brothers’ [Hammond and Nauman Scott] Black Top label and Allen Toussaint’s and Joshua Feigenbaum’s NYNO Records were active—as a third golden age of New Orleans R&B recording. Like the 1950s and ’60s and ’70s, he said, good songwriting was an essential ingredient in the city’s recording scene during his most productive years at Rounder. Billington’s writers included classic pop and rhythm-and-blues tunesmiths Doc Pomus and Dan Penn and Lafayette singer-songwriter-pianist David Egan.

“You can’t make a record without songs,” he said. “And it was possible then to make a good Cajun and New Orleans rhythm-and-blues records that sold enough to pay everybody and, occasionally, have a hit with Beau Jocque or Buckwheat (Zydeco).”

In addition to the book’s vivid chapters about artists and their sessions, Billington, a teacher of music production at Loyola University since 2014, offers aspiring producers practical studio advice.

“Like making sure everyone’s instrument works before going in the studio,” he said. “Or realizing how important the headphone mix is.”

Beyond straightforward technical considerations, Billington believes in fostering a family atmosphere.

“It’s an intimate situation, making records the way that I have, because it’s about the dynamics of all of those people,” he said. “Part of being a record producer is being a casting director who assembles people who love being with each other and creating together.”

Obviously, making tracks has never been just a job or paycheck for Billington.

“It’s about making the best record that I can make, and having faith that the business will follow,” he said. “When musicians coalesce in the studio and play something that makes me pinch myself, it’s the greatest feeling in the world.”