The true secrets of Edward “Kid” Ory (1886-1973) might still lie locked up in Gregg shorthand—a form of stenography that was invented by John Robert Gregg in 1888—in a series of loose sheets recovered after Ory’s death and assembled by his second wife, Barbara GaNung. That’s because biographer John McCusker, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer for the Times-Picayune, couldn’t find anyone to transcribe the original Gregg shorthand account of Ory’s life in his own words. McCusker did have access to later versions of the story in plain English, but GaNang produced a version, ultimately, where McCusker says, “The stories are real, but the narrative timeline is artificial.” This, ironically perhaps, gave McCusker a certain freedom. He could concentrate on the stories and assemble a hopefully truer timeline.

McCusker had to write the book twice, actually, after his first version vanished under eight feet of Katrina waves. That tough story splendidly matches his subject, because Kid Ory, born Creole, born broke, had to fight for everything he got. His first band threw their instruments together from cigar boxes, soap boxes, dinner pails and fishing line. Ory and his men sometimes stole horses from one of Ory’s relatives to ride into town and size up the competition.

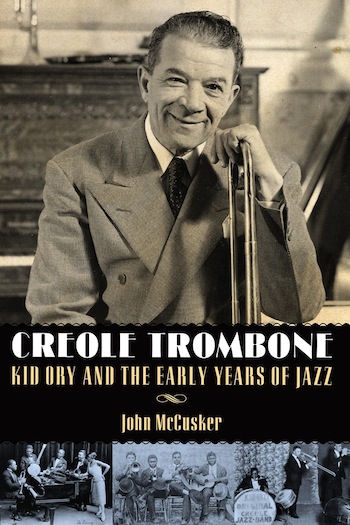

Ory wrote his signature tune, “Muskrat Ramble,” on a saxophone, but his trademark instrument remained trombone. He performed and/or recorded with King Oliver, Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton, and many others. The sides he cut in 1921 in Los Angeles, on a chronically-malfunctioning hand-cranked wax-disc machine, are quite possibly the first jazz records cut by a black band—although Ory, to the end, would always respond, “I’m Creole” to any question about his race.

McCusker includes a photo of one of those sides, “Maybe Some Day.” A very different label pokes through, in some worn patches, the label record buyers were supposed to see. That’s because of a dispute over who actually owned the rights. The man’s story remains, as McCusker admits, a frayed narrative with opposing narrators punching through each other to be heard. Against that, though, the music remains. “Ory’s Creole Trombone,” 91 years old this year, surmounts all narrative. It fulfills as experience.