In the heyday of New Orleans rhythm and blues, it was rare that sidemen on a recording session were credited. Yet jazz aficionados are aware that it was Idris Muhammad behind the drums on an array of superb albums from the likes of pianists Ahmad Jamal and Randy Weston, saxophonists Pharoah Sanders and Lou Donaldson and others.

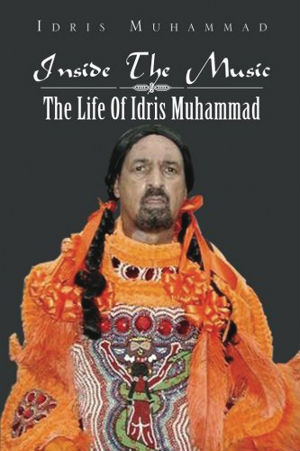

In the ’60s, and against the advice of some business people, Leo Morris changed his name to Idris Muhammad when he became a Muslim. In his autobiography, the drummer takes the reader on his journey from a nine-year-old Morris playing on the back of a truck in a Mardi Gras parade to his adult career performing on stages and in studios around the world. No matter how far he traveled, however, his hometown of New Orleans remained in the pulse of his drumbeat.

Muhammad is undoubtedly the only drummer whose technique on the hi-hat cymbals has been inspired by the sound of a steam presser. His family lived at 1220 Lyons Street next door to Buddy’s Cleaners and Pressing Shop. “I hear this: Cracka-chew…pssst taugh… over and over again,” he writes. “Practicing the drums next to Buddy’s Cleaners, I started copying this rhythm…”

This book is full of wonderful insights into Muhammad’s distinctive style that made him a much in-demand musician. The reason he wraps his drumsticks in tape like a tennis player’s racket is because he had to switch to metal sticks after breaking his arm falling off of some monkey bars. The sticks made his hands black so he wrapped them. He continued the practice throughout his career and later chose red tape—his signature color.

To this day, Muhammad, who at 73 has retired in his hometown, declares, “I’m a funk player. I’m not a jazz musician.” The drummer, who also led and recorded his own jazz/funk groups, tells the story of the great bandleader and drummer Art Blakey putting him in a bear hug and saying, “You’re one of us [jazz musicians] and I’ll squeeze you until you say you’re one of us.”

Considering all the local references and Muhammad’s look back to New Orleans as it was in the late ‘40s and ‘50s, readers, and particularly New Orleanians, don’t necessarily have to be music buffs to enjoy this book. Part of the joy is that it is all in Muhammad’s voice without filler or interpretation. He’s telling the story in his own words, his own jargon that, like his music, speaks of New Orleans.