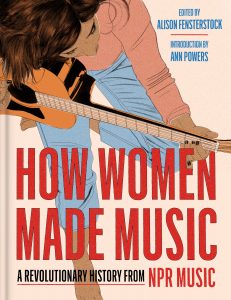

New Orleans writer and WWOZ radio host Alison Fensterstock is the editor of How Women Made Music: A Revolutionary History from NPR Music. Inspired by National Public Radio’s Turning the Tables series, How Women Made Music contains a lively bounty of engaging essays and interviews, many of them culled from NPR’s 50 years of music coverage.

Fensterstock, a former staff writer at The Times-Picayune, has written freelance stories for Rolling Stone, The New York Times, Oxford American, MOJO, OffBeat and other publications. An NPR contributor since 2016, her public radio work includes writing and editing the female-centric series Turning the Tables. She participated in the How Women Made Music book tour this fall, appearing in several cities with local writers who contributed to the project.

This is not a question—what a great book you’ve put together.

Thank you. Obviously, I had amazing material to work with.

How did the book tour go?

More than 100 writers, illustrators and photographers contributed to the Turning the Tables series. Many of them are in the book, so, everywhere I went on tour, I had a different group of contributors to talk to in a panel setting onstage. That made every conversation interesting for me. In the spirit of the book, every tour event featured different voices raising new questions, looking at things from different angles, engaging with our core ideas in diverse ways.

What sort of reaction is the book getting?

Really good. I haven’t seen a bad review yet, even from internet commenters. One of the trade publications, Booklist, called it “not just a book about women in music—the book about women in music.”

Ann Powers. Photo by Emily April Allen.

Ann Powers, the NPR music critic and correspondent, writes in the book’s introduction that she as well as you and Jill Sternheimer [director of public programming at Lincoln Center] were inspired to create Turning the Tables, the NPR series about women musicians, after you saw Barbara Lynn perform at the 2015 Ponderosa Stomp.

I met Ann and Jill through the Stomp when I worked for the conference part of the event. It’s a neat tale of a bunch of women linking up through an event that, as cool as it was, did not have gender parity. The Stomp artists, attendees, authors and historians at the conference were overwhelmingly dudes.

Barbara Lynn, the left-handed guitar slinger from the Texas Gulf Coast, was a Stomp regular. Absolutely killer, but totally one of the artists that we in New Orleans get to see relatively often and casually. She blew Ann’s and Jill’s minds. That started the wheels turning—why don’t more people know about her?

The goal of the Turning the Tables series was to recognize the contributions of women musicians?

The [male dominated] pantheon of pop music appeared to be set in stone. Nothing against the Beatles and Nas, etc., but it was a boring and fossilized take. So, the idea was that if we do a new assessment of “greatness,” but have men sit this one out, we will see a completely different, equally deserving, interesting and revolutionary pantheon emerge. It’s not that women weren’t as important as Mick Jagger or Jerry Garcia or Jimi Hendrix, it’s that institutionalized biases kept them from being assessed on the same level.

NPR Music asked you to be the book’s editor.

An NPR Music editor I had worked with called and said they wanted to turn Turning the Tables into a book. I said definitely, yes—because freelancing is unpredictable and sort of mentally distracting, hopping from idea to idea and short gig to short gig. It was nice to have one project to go deep on and have a job that would last a while. More seriously, this felt like a really meaningful thing to be a part of.

Alison Fensterstock. Photo courtesy of Alison Fensterstock

NPR has a vast archive. How did you go about selecting material for the book?

A lot of the material from the ’00s and beyond is online, particularly after NPR Music was established. I also had the archivists working for NPR headquarters, which was invaluable. They sent me transcripts and audio dating back to when NPR was founded. That’s part of why the book took a long time, but I was pleased to discover NPR has been doing in-depth interviews with artists since the ’70s. That gives the book a breadth across time. It wasn’t just: “It’s 2024 and we all agree Tracy Chapman’s debut in 1988 has borne out as important and here’s this critic’s perspective looking at her legacy.” It was that and also: “And here is Tracy Chapman in 1988, talking at length, in the moment.”

You’re the editor of How Women Made Music, but did you consult with Ann Powers and others at NPR?

One of the reasons they hired a freelance editor was because Ann was finishing her tour de force Joni Mitchell biography, while also doing her regular job at NPR. And like all media/nonprofit staff, the rest of the NPR Music team had more-than-full plates. Ann was always available for a consult, and she approved every step, but I feel honored that I was trusted to largely assemble this on my own and then bring it to her and the NPR Music team and the publisher.

The audio book combines original audio from NPR’s archives plus some readings of text.

I chose all the audio and did the sequencing because it follows the order of where transcriptions appear in the print book. We have the original archival audio, which I think is the coolest part, and a few different voice actors reading it, plus Ann Powers and I do some reading as well. It makes for a fun listening experience, especially when you get gems like Patti Smith being interviewed in 1976, with her South Jersey accent still so strong, or Joni Mitchell talking about a conversation she had with Georgia O’Keeffe and imitating Georgia’s voice, or just anything with Dolly Parton.

New Orleans is well represented in the book—but not only because that’s where you live, but because the city’s music and artists deserve recognition.

Of course, they do. Irma Thomas is in there, because I wrote a short essay about her in 2017. Mahalia Jackson is there because Gwen Thompkins went to the mat for her inclusion in the 2019 series on pre-rock, pre-album-era titans. I was also thrilled to include Mia X. New Orleans is well represented in the book because, as you say, New Orleans music and artists fully deserve their place, but also because contributors like Gwen and I live here, too. I was delighted to be in a position to make sure New Orleans was properly lauded.