Alex Chilton loved New Orleans, even though he had to wash dishes to live here. Actually, washing dishes wasn’t the first job he took in the city after moving from his native Memphis in 1982. The man often considered one of the great pop performers and songwriters of his era, went to work first making calls for someone running for mayor. We don’t learn whom, from Holly George-Warren’s account, but Chilton’s friend George Reinecke got him the job. “The people in charge gave me and Alex shit for pronouncing the guy’s last name incorrectly, so that only lasted a few weeks.”

Memphis had seen Chilton through from birth, through three distinct musical careers: As a teen with the Box Tops, as a young man with Big Star, and then his early, scatter-shot, sometimes-self-defeating solo career. He had reasons for his bitterness, which had turned him into an angry and sometimes dangerous soul. New Orleans seemed to give him new purpose, even if that new purpose consisted, for a time, of living without a telephone and jamming endlessly while the first Mothers of Invention album circled the turntable. He was rebuilding himself musically, but he could still snap and threaten at slights, at chance remarks. He had a lot to hide.

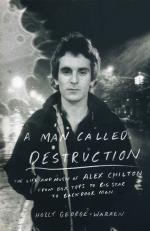

George-Warren gets all of Chilton down righteously, before and after the rebirth. Born to jazz musician Sidney Chilton (whose obituary described his son as a “rock and folk” singer), the young man seemed to single-handedly suck up everything that Memphis had to teach, musically, and shared it with the world. Of course, the world often did not care. The man died too young, still troubled, albeit relieved of dishwashing duties. We can feel fortunate for the work, which remains.