Nothing starts an argument like a list.

When the American Film Institute (AFI) announced what it considered the Hundred Greatest Movies last May, critics and moviegoers pounced on the list, questioning, among others, The Graduate at number seven and the sentimental It’s a Wonderful Life at number eleven. The AFl may have intended for the list to establish an American film canon, but instead it started an ‘unprecedented national debate, causing people to think passionately and articulately about film values in a way they rarely do over coffee after a show. David Letterman may mock the whole idea of top ten lists nightly, but the joke is lost on those who snort and harrumph at the bad taste they see in Billboard’s charts and the New York Times’ best seller lists. With a subtitle that promises to name “75 Great Rock and Pop Artists From Vaudeville to Techno,”

When the American Film Institute (AFI) announced what it considered the Hundred Greatest Movies last May, critics and moviegoers pounced on the list, questioning, among others, The Graduate at number seven and the sentimental It’s a Wonderful Life at number eleven. The AFl may have intended for the list to establish an American film canon, but instead it started an ‘unprecedented national debate, causing people to think passionately and articulately about film values in a way they rarely do over coffee after a show. David Letterman may mock the whole idea of top ten lists nightly, but the joke is lost on those who snort and harrumph at the bad taste they see in Billboard’s charts and the New York Times’ best seller lists. With a subtitle that promises to name “75 Great Rock and Pop Artists From Vaudeville to Techno,”

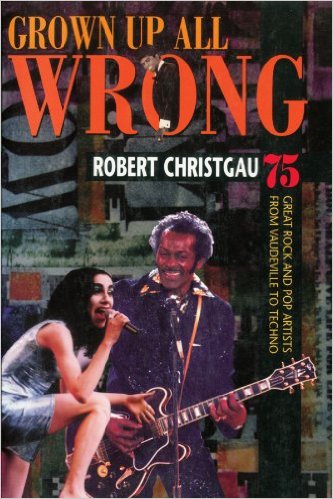

Robert Christgau’s Grown Up All Wrong should start similar discussions. The subtitle is, in truth, a hook playing on our love of lists because the book is not really an argument for the 75 artists included. Instead, Christgau has compiled a collection of 75 essays, some focusing on artists like Neil Young, James Brown, Al Green and Aretha Franklin that would be in any book on greatest artists.

On the other hand, those skimming the table of contents may wonder how Ray Parker Jr., Lynyrd, Skynyrd and the B-52’s snuck into this book. With the exception of Skynyrd, whose working class sensibility he always found credible, it’s unlikely Christgau would make a spirited argument for the grand importance of any of these bands, but his pieces suggest there is more to them than people might think. The subtitle may promise a list of rock ‘n’ roll greats, but Christgau writes, “These essays … don’t circumscribe a canon-Louis Jordan, the Coasters, Thelonious Monk, Bob Dylan, Steely Dan, the Ramones, and Luamba Franco [none of whom appear in the book] are all in mine.”

Christgau is perhaps best known for his “Christgau’s Consumer Guide” columns in The Village Voice, where the discipline of one paragraph reviews forces him to condense ten lines of commentary into a single sentence. He once accurately described the Ramones as ”’clean the way the [New York] Dolls never were, sprightly the way the Velvets never were, and just plain listenable the way Black Sabbath never was,” and caught. the essence of Steely Dan writing, “craftsmen this obsessive don’t want to rule the world-they just want to make sure it doesn’t get them.”

The writing in Grown Up All Wrong is less compressed, but the habit of provocative concision has taken root, so. sentences suggest a thought or angle that helps put an artist in perspective even as they dare readers to disagree. His thoughts on Stevie Wonder begin, “Stevie Wonder is a fool” en route to an analysis of his blindness and its possible role in making Wonder’s music is what it is.

In The New York Times, Christgau’s writing was criticized as having a “labored writing style that tends to grate,” and at his worst, there is something to that. He can occasionally get trapped in the no man’s land between “the academy and the barroom, but more often than not he successfully adopts the right voice to evoke the essential character of title music while discussing it in the serious, intellectual manner the best deserves. For every line lost in the thicket of academic prose, there are twenty as efficiently accurate as his assessment of Mick Jagger’s voice (“His drawl recalls Christopher Robin as often as Howlin’ Wolf.”) or his defense of country music (“I care about country because country is this century’s most credible music of domestic life.”).

His clever lines would be worthless if Christgau didn’t have the intellectual chops to back them up, but fortunately he does. His essay on the Rolling Stones portrays them as young bohemians, while his piece on George Jones focuses on Jones’ as a pure voice, possessed by a blank slate. In perhaps his grandest proclamation, Christgau boldly declares James Brown “the greatest rock and roller of all time,” then recounts the dissension of other critics, one of whom cited Brown’s lack of “verbal content”.

Readers may agree with the other critics, but Christgau makes a sufficiently interesting case for Brown’s ability to create “dance music that passeth all understanding–arguing that “there’s also a lightness about him, a transcendent impulse that’s built into his concept–that it’s hard not to go back to Brown albums to try to hear what he hears. In fact, the path from the book to the record collection may end up well-worn by the end of Grown Up All Wrong because it’s hard, for instance, to imagine readers not wanting to re-hear and reconsider Plastic Ono Band after reading his thoughts on John Lennon.

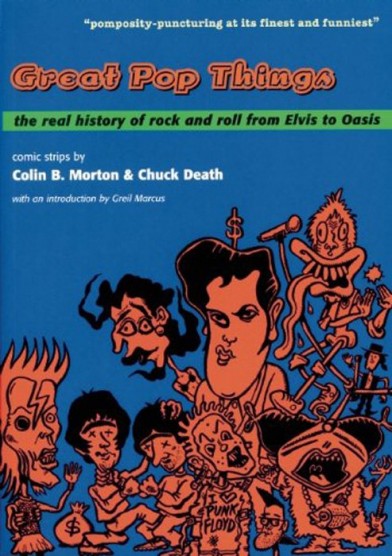

While the essays in Grown Up All Wrong suggest that we need to rethink many of our most important pop artists, Great Pop Things: The Real History of Rock from the Elvis to Oasis suggest we should reconsider the whole enterprise. Great Pop Things is a book of comic strips by Colin Morton and Chuck Death that rewrite pop history to make it funnier and in a way, truer. As they tell it, Elvis was managed by Col. Sanders, Jean-Paul Sartre was Led Zeppelin’s bass player, and U2’s Bono is the son of Sonny and his wooden actress wife “Chair.”

While the essays in Grown Up All Wrong suggest that we need to rethink many of our most important pop artists, Great Pop Things: The Real History of Rock from the Elvis to Oasis suggest we should reconsider the whole enterprise. Great Pop Things is a book of comic strips by Colin Morton and Chuck Death that rewrite pop history to make it funnier and in a way, truer. As they tell it, Elvis was managed by Col. Sanders, Jean-Paul Sartre was Led Zeppelin’s bass player, and U2’s Bono is the son of Sonny and his wooden actress wife “Chair.”

Morton and Death (the latter a pseudonym for the Mekons’) Jon Langford, whose Curse of the Mekons is discussed in Grown Up All Wrong) do more than just pun and goof on people’s names. Like Bruce Campbell in the third Evil Dead movie, they wield a chainsaw in the most sarcastic spirit possible to go after anyone unfortunate enough to be an icon. After this book, David Bowie will forever be known for his movie, “The Man Who Failed To Act: and Sid Vicious will be remembered for living with Nancy.

Nancy Sinatra. These strips skew history to capture the essence of a band or artist’s story in Great Pop Things, as in the case of the strips on Roxy Music that highlight the schizophrenia; they show Bryan Ferry, in his role as Roxy Music bandleader, firing himself-jealous of his concurrent solo success. A strip on ABBA revealing its affair with Fleetwood Mac shows that once a band’s soap opera is larger than the music, it no longer matters who’s involved in the story.

Pop music is in one sense as frivolous as its name implies, but it reflects who we really are and what we like, as opposed to “high art,” which reflects who we wish we were. Christgau, Morton and Death/Langford deal with pop issues not in the gentle, rational salesman voice that can make anything seem likely; instead, they talk about them in the iconoclastic, contradictory, half-rational way we do. They tell us how the pop world looks to them, but in voices that invite disbelief and challenge. As they engage us in debate, they make us think more about our relationships to the pop lives we live, and by doing so, they make Grown Up All Wrong and Great Pop Things important.