The blues imply a story. Every “hurts so bad” lyric is a moment caused by something that happened in the past; someone or something made the singer hurt that bad.

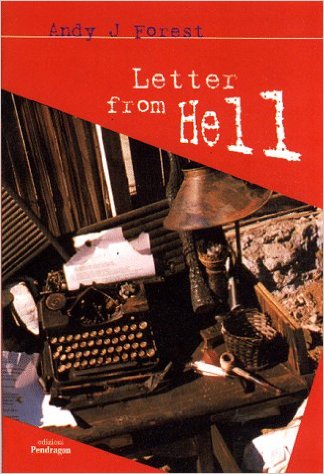

The blues are also a literary form. The voice can only convey so much pain, so it takes an intelligent turn of phrase to convey the dimensions of the pain and to make the song distinctive. New Orleans’ blues harmonica player Andy J. Forest has recently flexed his literary muscles, writing Letter From Hell, a tall tale about life on a road that takes a very wrong turn.

It won’t make anyone forget Faulkner, but it is a fun first book with some real insight into parts of a musician’s life few know much about.

Letter From Hell is the story of five strangers who end up hired to play New Orleans music in a circuit of European blues clubs, but Forest’s storytelling is more ambitious than this synopsis makes it sound. He uses children’s stories and dreams co give insight into his characters, and when everybody dies about halfway through the book, he creates a new kind of Hell that is as much as Beetlejuice as Dante.

Letter From Hell is the story of five strangers who end up hired to play New Orleans music in a circuit of European blues clubs, but Forest’s storytelling is more ambitious than this synopsis makes it sound. He uses children’s stories and dreams co give insight into his characters, and when everybody dies about halfway through the book, he creates a new kind of Hell that is as much as Beetlejuice as Dante.

As entertaining as that idea is, it’s not entirely successful. As funny as a fast talking hustler Beelezebub sounds, it’s at odds with the more natural tone of much of the book. Unpredictable cone shifts like this one occur occasionally, muting the tallness of the tale, but they don’t diminish the accuracy with which Forest describes musicians’ lives.

Since the industry surrounding music obscures the twenty-two or so hours when {he musician isn’t on stage, it’s easy to miss the realities of the musician’s life.

Forest sheds some light on the subject by showing the mundane truth. He shows the drummer-always the drummer-driving everybody crazy in the tour van, and the bass player getting paid by the others to do their laundry in her hotel room sink. He captures their eccentric motivations. and shows the almost blase attitude musicians can develop coward their itinerant lifestyles, accepting good fortune and bad with equal aplomb.

Such revelations are not Letter from Hell’s focus; it is a folk tale, where the natural and fanciful meet on undecided turf. Such stories are not easy to tell, but Forest does a good job, only occasionally wobbling.

However, Forest is completely assured on the accompanying CD, where the skills that first brought him to public attention are strikingly evident. Forest brings the band’s music in Hell to life on a CD that shows why he is one of the cop harmonica players in the city. The Letter from Hell project as a whole is an ambitious one, but one Forest handles well, merging literary and musical worlds in a way that hasn’t been done before.

Top 40 radio, once synonymous with lightweight pop ness, seems bizarre in retrospect. In 1960, Elvis, the Everly Brothers, Anita Bryant, Roy Orbison and Ferrante & Teicher all made it to number one, and in 1973, Edgar Winter’s “Frankenstein” reached the cop along with “Smoke on the Water,” “Dueling Banjos,” “Killing Me Softly With His Song” and “Delta Dawn.”

Top 40 radio introduced listeners in their early teens co a range of music unimaginable today, and Rolling Stone writer Ben Fong-Torres tells its story in The Hits Just Keep On Coming.

In his introduction, Fong-Torres says he chose to write his book “like a radio show,” and he was more successful than he may realize. He keeps the book moving and varied, featuring history, Q & A, sidebars and factoids, but like Top 40 radio, The Hits Just Keep On Coming is erratic. The writer successfully illuminates the pressures the format created for disc jockeys by telling stories of jocks being chewed out for sins as minor as playing an instrumental after the news, but the reprinted DJ patter doesn’t come to life without a hyperactive baritone voicing it.

Just as Top 40 was a smorgasbord of different styles, Fong-Torres’ book gives listeners tastes of different things they can further investigate on their own.

Ultimately, the strength and weakness of The Hits Just Keep on Coming is Fong-Torres’ nostalgic affection for the format. That affection keeps him from asking the really hard questions or revealing who was a loser, who was needy, and who was a loner. He does let a few drinking problems creep into the text, and drugs are mentioned, but the disc jockeys are depicted as the nice guys they seemed to be on the radio.

Still it’s hard not to feel the writer’s enthusiasm for a more interesting period in radio. Today the local is being bled out of radio) formats are narrowing, and New Orleans’ “bad boy” alternative station proves its outrageousness by bleeping Alanis Morrisette’s dirty words.

Another labor of love is New Orleanian Bruce Spizer’s Songs, Pictures and Stories of the Fabulous Beatles Records on Vee-Jay. Once Capitol Records passed on its right to release Beatles’ records in America, Chicago’s Vee-Jay Records picked them up. After Capitol realized what it had done, it sued and after a period of legal wrangling, won the rights to the Beatles; but Vee-Jay still retained the right to use sixteen songs for a short time.

To capitalize on their luck, Vee-Jay released the same sixteen songs on different labels and repackaged the same songs in different configurations on six albums. It is this unusual chapter in music history that Spizer focuses on.

As an artifact, The Fabulous Beatles Records on Vee-Jay is a window into another world. It is an oversized, heavy book on glossy paper with gorgeous, full-color reproductions of record labels and album packaging.

Because it is essentially a collector’s book, it pays far more attention to serial numbers of singles and albums than a story. Who did what takes a definite backseat to discography information. For non-collectors, it’s hard not to look at such a book and contemplate the priorities and values reflected by it, but for its market, it’s hard to imagine a more handsome or a more thorough book.