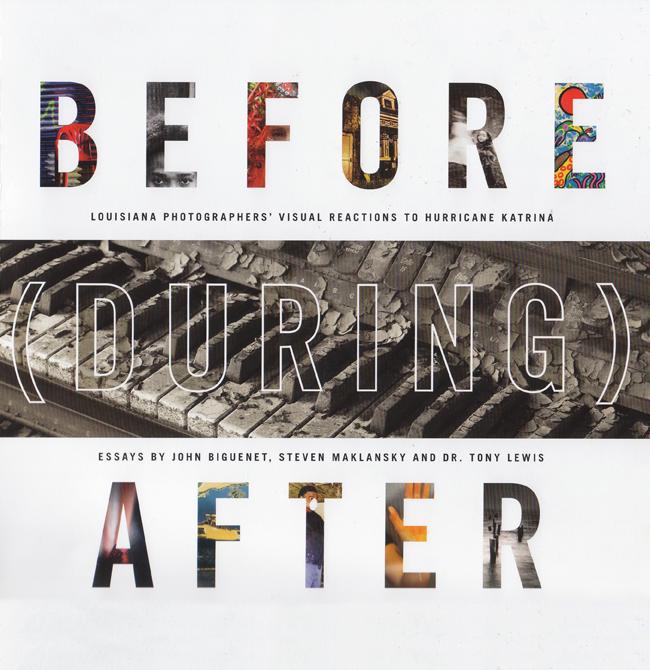

[UPDATED] Before During After speaks to the power of Hurricane Katrina, though not in the way it intends. Photographer Elizabeth Kleinveld had the provocative idea to document how Katrina affected people—in this case, photographers—by looking at the work they did before, during and after it. That means that there are only two or three Katrina-related photos for each of the 12 photographers chosen, but Katrina’s gravity is such that everything comes back to it. John Biguenet has written a forward and afterward for the book, but they’re about Katrina. Louisiana State Museum’s Dr. Tony Lewis contributed an essay titled “Hurricane Katrina: The Aesthetics of a Disaster,” but he discusses Katrina-related photography, not the story of change that is the book’s purpose. Even some of the “After” photos feel more like a continuation of Katrina coverage, such as Zack Smith’s portrait of a somber Blair Gimma struggling to make human connection, or the woman whose face is partially obscured by a warped, mud-covered record album.

[UPDATED] Before During After speaks to the power of Hurricane Katrina, though not in the way it intends. Photographer Elizabeth Kleinveld had the provocative idea to document how Katrina affected people—in this case, photographers—by looking at the work they did before, during and after it. That means that there are only two or three Katrina-related photos for each of the 12 photographers chosen, but Katrina’s gravity is such that everything comes back to it. John Biguenet has written a forward and afterward for the book, but they’re about Katrina. Louisiana State Museum’s Dr. Tony Lewis contributed an essay titled “Hurricane Katrina: The Aesthetics of a Disaster,” but he discusses Katrina-related photography, not the story of change that is the book’s purpose. Even some of the “After” photos feel more like a continuation of Katrina coverage, such as Zack Smith’s portrait of a somber Blair Gimma struggling to make human connection, or the woman whose face is partially obscured by a warped, mud-covered record album.

Kleinveld presents six to eight photos by a dozen photographers, and the premise is that these tell a story of change. Unfortunately, such a small sampling makes such stories misleading. Jonathan Traviesa is represented by three portraits (before) and two low-angled, unpeopled landscapes (after), and it’s tempting to think about how his Katrina experiences on Bayou St. John led to that change—except that he didn’t stop shooting portraits, and the relationship between the subjects and the spaces they inhabit continues to matter in his work. Eric Julien didn’t have his camera with him during his Katrina exile, so he started making mixed media collages, and his “after” is represented by more collages. He hasn’t quit shooting photos, though, as his sequence would lead you to believe. I suspect that if you looked at any photographer’s collected work and pulled out six to eight shots from different periods, you could tell 10 different stories depending on the choices.

That said, Before During After does suggest the way an artist’s process changes. Frank Relle’s photos now look largely like his pre-K shots, but he started using lights to shoot architectural photos because the city was so dark after Katrina that he couldn’t count on natural nighttime light to be sufficient. Lori Waselchuk started shooting with a panoramic camera to capture the vastness of the damage, then found its broad sweep spoke to her for other situations.

In the end, the strength of Before During After is the photographers’ work. They may not say what the book suggests that they do, but as a collection of photographs, it’s strong, with a few precious visions and a number of remarkable shots. No “during” photo is as surreal as one of David Rae Morris’ “before” shots, taken before the start of a Mardi Gras parade. And if the Katrina shots seem more documentary than artful, that may be further evidence of its gravity.

September 3, 10:07 a.m.

Dr. Tony Lewis works for the Louisiana State Museum, not Louisiana State University. The text has been changed to reflect that correction.