Dennis McNally has written two very useful books on American culture—an extremely well researched biography of Jack Kerouac, Desolate Angel, and an inside onlooker’s slightly jaundiced account of the Grateful Dead’s history, A Long Strange Trip. Highway 61 is another kind of book, a brilliant and provocative polemic that is about culture as a flashpoint of American idealism.

It’s McNally’s story of the U.S.A. plotted as a history of ideas that holds up a magic mirror to the overriding dilemma created by the founding fathers. How can a nation born from the tenets of Enlightenment moral philosophy search for freedom and equality for its populace while building its economy on slave labor?

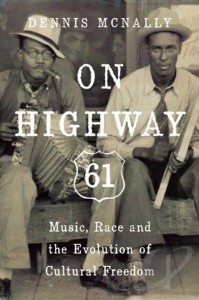

The book is also, to quote one of its main subjects, Bob Dylan, about “love and theft.” Hence its subtitle: Music, Race and the Evolution of Cultural Freedom. McNally uses the history of American institutional racism as an organizing principal to further his discussion about the ways in which African American culture has influenced the popular music landscape.

The argument requires reductive streamlining to fit such broad terrain into a narrative trajectory but McNally is ingenious in outfitting critical arguments to move the story forward. McNally ties 18th century philosophy to minstrelsy and the birth of jazz in New Orleans from Creole and black sources; through the northward migration of blacks that created urban blues; the arrival of bop as a manifestation of black consciousness; and the onset of rock ’n’ roll and the folk revival as a parallel to the Civil Rights movement.

The final third of the book is an account of the early career of Bob Dylan plotted against the real life drama of violence visited on the Freedom Riders and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) by segregationists in the south. It’s a riveting new look at Dylan’s history from a critical perspective that identifies him as a spiritual descendent of Henry David Thoreau and Mark Twain.

McNally wanted to feel what it was like to be in New Orleans pursuing the muse, just as so many of the people he wrote about in the book did. He wanted to “hear the train whistles and the fog horns.” I believe he found what he was looking for, and expressed it in this description of Bob Dylan writing “Mr. Tambourine Man” in New Orleans in early 1964:

Mad Mardi Gras visions, a pinch of Fellini’s La Strada, the phrase jingle jangle from Lord Buckley, and perhaps his friend Bruce Langhorne’s big Turkish tambourine all went into the song “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

Many assumed it was about drugs, since it uses a phrase—“take me on a trip”—that actually came to have a drug reference somewhat later… “Mr. Tambourine Man” is about transcendence, about escaping the wheel of suffering, about waking up and being free. Who is the tambourine man? First, he’s the source of the rhythm, but he’s the source of the music itself, of inspiration, of salvation. He’s the muse (has there ever been a male muse?). It’s a prayer of sorts, an invocation to the muse to cast his spell, which the singer vows to submit to.

McNally’s premise that America is at once haunted and inspired by its tragic connection to slavery still applies to the country today as it sits paralyzed by reactionary forces intent on rolling back the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts of the mid-’60s. McNally could have extended his premise to encompass hip-hop, Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown because the root causes of the problem he identifies are still being played out on the evening news.