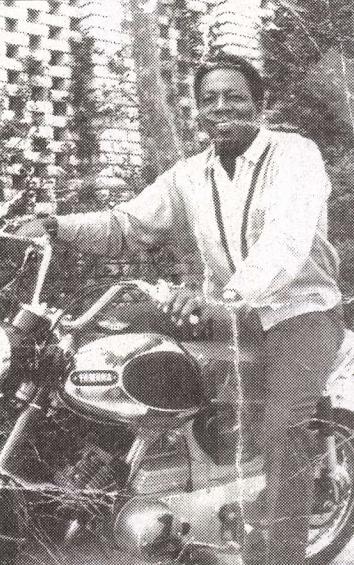

Currently holding down the weekend graveyard shift at Blues 1280, WODT, smooth-voiced Walt Boatner is a pioneer in black New Orleans broadcasting. Besides being a mainstay of New Orleans AM radio in the 1960s, between 1969 and 1972 he hosted the Walt Boatner Show, a very popular local African-American dance/music television program. Think of a local version of Soul Train, and you’ve got an idea of what the Walt Boatner Show was like.

Born in Centerville, Mississippi, November 10, 1938, Boatner moved to New Orleans after stints in the Air Force and community college. “My goal in life was to get out there and do something,” said Boatner.

“That’s what brought me to New Orleans in the early 1960s. My first job in broadcasting was at WYLD. I worked there for several years and then went to Shreveport for a short time. Then I came back to New Orleans at WBOK as the third Okey Dokey. You see the name Okey Dokey was owned by the station. The first Okey Dokey was James Smith. (The most famous Okey Dokey, Smith skirted a murder charge but it destroyed his career.) They replaced him with Louis Haywood. I took his place. I did that for a year. These were the days of personality radio. At WBOK we had Hot Ziggity, Honey Boy, the Screamer Teamer, and Mama Lou. Everybody had their own on-air personality to make them different. We didn’t realize it at the time, but the music we were playing was special and it excited us. Today’s music just doesn’t do that.”

An astute business man, Boatner parlayed his radio contacts into other ventures—a record shop, located on Louisiana Avenue, and a nightclub on South Claiborne Avenue. “I was back at WYLD working part-time when the television show started,” continued Boatner. “I wanted a means to advertise my businesses. So I approached Channel 26 and bought an hour of broadcast time. I didn’t exactly know what I was going to do with that hour, but I wanted to aim a show at the black community. I thought having a show with African-American kids on it dancing to the hits of the day might work and be good for the community. At the time there was the John Pela Show, but they didn’t have black kids dancing on it. (OffBeat Associate Editor Bunny Matthews was among the teen dancers on the John Pela Show. Eddie’s Three Way Record Shop also had a black dance/music program on Channel 26 hosted by Cinnis Edwards. It predated Boatner’s show by about a month but lasted only one year.)

“I got in touch with some of the schools and asked them if they could contact some kids to see if they wanted to dance on the show. The kids would come down to the record shop and I’d audition them. Everyone that was featured on the show had to have a routine. We had regular kids dancing, but we featured kids that had routines. I auditioned dozens of kids every week. The schools were tickled to death because it gave the kids something to do after school. All the shows were broadcast live from the station’s studio in the World Trade Center.”

The show was an immediate success for Boatner and Channel 26. After six months, W.G.N.O.’s station manager Dave Wagenfort hired Boatner to host a weekly one hour show in the afternoon beginning at 4 p.m. In exchange, Boatner got two hours of free broadcast time on Sunday between 1 a.m. and 3 p.m., and shared in the revenue the weekday show earned.

“At that point I started getting lots of mail from parents so I knew the show was doing real well,” said Boatner. “They thanked me for hosting the show. They said they didn’t have to worry about their kids after school because they were either on the show or watching it on television. The kids were great and really loyal to us. They couldn’t wait to get out of school to get down to Canal Street to get on the show. We used to let kids pantomime their favorite record—they call that karaoke now. That was a real popular part of the show. In fact, one of the first times we had a white kid on the show was to pantomime a record. He called me and came down to the shop. He was a nice young man, a senior in high school. But because of the format of the show, I wasn’t sure he would work. But he made the appearance and everybody really enjoyed it. This fellow called me out of the blue about 15 years ago and made me aware of who he was. He thanked me and told me he was a big executive with an oil company. That made me feel pretty good. But you know a lot of kids that were on the show became successful and valuable members of the community.”

Boatner’s show also featured many artists making live appearances lip-synching their latest record. “I had all the local people on,” continued Boatner. “Ernie K-Doe, Willie West, Eddie Bo, Chuck Carbo, Jean Knight, King Floyd, Tony Owens, the Meters, Johnny Adams and Irma Thomas. The first national artist we had on the show was Lou Rawls. He was making an appearance in town and he stopped by. Then we had people like Gene Chandler, Jerry Butler, Little Johnny Taylor, and Aunt Esther (LaWanda Page) from Sanford and Son. She was appearing at my club at the time.

“Concert promoters would arrange for artists to make appearances to advertise their dates. The record companies also kept me up to date too by getting me the latest records right away. But the thing about me was, I’d play a good record even if wasn’t promoted, and I wouldn’t play a bad record if it was promoted.”

Being that the show was broadcast live, occasionally there were embarrassing moments. “There was an instance—and I don’t want to call this young lady’s name because she went on to become very famous and very rich,” laughed Boatner. “She was the floor manager for the show. Remember, these were the days when the afro and the miniskirt were in. Well, the camera focused in on this lady and her skirt was just a little too short. Well the poor child didn’t know this and you know what was broadcast on all over the city. It was embarrassing because it was live TV and we couldn’t stop it. I had to give the cameraman a piece of my mind after the show.”

The Walt Boatner Show lasted three years until WDSU was sold. Unfortunately, the new owners wanted to go in a new direction and they jettisoned the program despite objections from the black community. Ever the entrepreneur, Boatner continued to run a club and a record shop as well as another business venture. “I’m also a commercial pilot and a certified flight teacher,” said Boatner. “I bought an airplane for my own enjoyment, but I started running into guys that wanted to learn to fly. I said to myself, ‘Hey, maybe I should start teaching people to fly.’ So I ran into another pilot and asked if he’d help me out and he did. I rented a hangar at Lakefront Airport and started a school with one plane. In six months, I had bought two more. When it was all said and done, I had eight planes and five instructors.”

Around 1978, Boatner moved his record shop to the corner of Canal and South Rampart Street, which provided another challenge. “Ive been told it was the first black-owned business in the CBD,” said Boatner. “It was located on the lake side of Rampart Street and I was told that every business that was located on that side of the street failed. Well, I proved them wrong for several years. From day one we had a very successful shop that catered to blacks, whites, tourists and New Orleanians.”

Walt Boatner’s Record Shop hung on until 1983, when, like many mom-and-pop record shops, Boatner couldn’t overcome the competition from the major record chains that had invaded New Orleans. This was also around the time his flight school closed. Boatner realized a fresh start was in order. “I moved to Alexandria,” he said. “Gus Lewis, who was a deejay at WYLD, bought a station there—KBEC—with another fellow from New Orleans. They asked me to be their station manager and do a show. I did that for six years. Then I started a newspaper, The Voice of Alexandria. It was a free monthly that did pretty good. I did that for about a year and then I sold it and got into the nightclub business with the Do You Remember? Club. It was a nice place that held about 800 people, but in Alexandria, no matter what kind of promotion you did, you could only draw a crowd two nights a week. That wasn’t cutting it financially, so I sold the club and moved back to New Orleans.”

For the last several years, Boatner has worked part-time at WODT. “I guess I never really left radio,” said Boatner. “I’ve always had some kind of connection with it. There’s no real money in radio unless you’re one of the big guys—I do this because I enjoy it. I like the blues, so WODT is a great fit for me. I’ve also started a business with my son. We’re trying to get people interested in local talent, so we’re going to put some shows on to expose it.”

Unfortunately, for those of us who’d enjoy unscrewing a vintage bottle of Ripple and viewing reruns of bell-bottomed and hot pants-wearing local teens doing the Cissy Strut while King Floyd and the Meter’s lip-synch their hits, you’re out of luck. “There are no tapes,” laments Boatner. “Because the shows were broadcast live they never taped any. My daughter went down to the station and they went through their files, but they couldn’t find any. I’ve had people approach me about doing a reunion of the show and someday that might happen. People still stop me on the street every day and tell me they remember the show or that they were on the show. I think that’s really something.”