Tucked away in a warehouse by the railway tracks on Saint Claude Avenue, the gates to New Orleans Record Press (NORP) are covered in multicolored vinyl platters. Inside, the warehouse buzzes with activity. A machine stamps newly minted records. A fresh vinyl disk drops every minute. Employees move buckets of vinyl pellets and place the final product in sleeves. Business is booming.

NORP started with a single, quarter-million-dollar record press and now has three in operation. A fourth will be added soon. At the beginning of 2021, the company had three co-owners and only three employees. Now they’ve expanded to four co-owners and 27 employees. The 300,000 copies of vinyl they pressed in 2021 has fueled their success.

Polyvinyl chloride plastic is used in vinyl records, floors, clothes and more. The pellets are melted into heated pucks that are then pressed inside of a stamping machine. Photo by Dalton Spangler.

“We’re hoping to crack a million this year, which is nothing,” said Mike Quinlan, one of the founders of NORP. “We have people calling asking to do 2.5 million pieces of vinyl for one artist this year.”

Over 41-million albums were sold on vinyl in the U.S. alone last year. Vinyl outsold CDs and comprised nearly a third of all albums purchased last year, digital or otherwise. This all seems like it’d be great news, but vinyl printing is struggling to keep up with rising demand.

In 2020, NORP could have an order of vinyl completed, start to finish, in eight to 12 weeks with a fraction of the labor. Now an order takes an average of six months and potentially much longer depending on pressing issues. This isn’t an issue facing NORP alone—even industry titans must wait longer.

Local artists, record stores and fans are forced to remain patient as wait times lengthen on new and reissued vinyl. Independent artists are struggling to squeeze into the back of the vinyl-printing line. The finger of blame points many directions, from delays at pressing plants, to shipping logistics, to lack of materials, to increased demand from major labels.

The astounding demand have left vinyl presses like NORP with an important question: Who gets their vinyl printed?

Major labels like Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group have been pressing vinyl for years. Still, their list of contracted record presses has expanded to meet the new demand including medium and small-sized presses like NORP.

“Every major label has called us in the last year and asked us what our capacity is—what we can do,” Quinlan said. “We work for several majors now, like Universal.”

NORP will tell the label how many records they’re able to print and the label sends them a seemingly unlimited list of releases. As soon as businesses like NORP offer more capacity, major labels will gladly fill the space. As Quinlan puts it, the only limiting factor is the number of records a vinyl press can make.

“And you still have a million people that don’t get their records pressed,” Quinlan said.

Major record labels are ordering vast quantities of vinyl, but many see the failure to meet demand as an industry problem. Bottlenecks in production slow down the process. It can take two months for NORP to get the materials necessary even to start printing.

One holdup in vinyl production is the manufacturing of master plates, which serve as the basis of any new print. Every time an artist orders printing for a new record, a new master plate must be produced. Most vinyl is copied by way of a lacquer disc which is sent to cutters around the country to be produced into master plates.

The inside of a record press has two stampers with microscopic grooves that make the vinyl plastic into a playable record. Photo by Dalton Spangler.

Apollo Masters Corporation, located in Banning, California, supplied 70 percent of the world’s lacquers before it was destroyed by fire in February 2020. The recording industry still hasn’t fully recovered from that loss. Today, the responsibility for manufacturing the majority of the world’s lacquer discs rests on a company called MDC, based in Japan. It takes time for the cutters to acquire lacquer, then cut the material to make master plates and then ship the product to presses like NORP. Damaged master plates in the pressing process aggravate the issue even more.

“We drove 400 vinyl records to Houston, Texas, the day of Tobe Nwigwe’s show because we said we’d get it to him for the show,” Quinlan said. “The process didn’t allow us to have it done when we hoped because the stamper broke. That happens all the time.”

Presses also need raw materials like PVC plastics. Sometimes NORP ships those plastics from as far as the Netherlands or Italy. Color variants can take even more time. Then there is the issue of quality control.

“It’s a lot easier to make a good-looking record than a good-sounding record,” Quinlan said.

Record presses need a good reputation to work with major labels. NORP has built clout by intentionally staying small since its start in 2017 until it could consistently mass produce high-quality records. They’ve created and mastered a four-station structure to inspect albums visually and audibly.

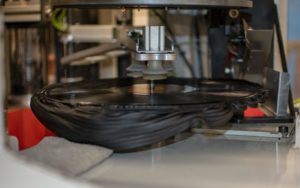

Excess vinyl plastic left after the press is cut off to be recycled into more records. Photo by Dalton Spangler.

The machines used to press vinyl present another potential pitfall. New machines take time to build and ship. Old machines are rare and a limited number of experts can repair them. The turnaround time for ordering a machine can extend beyond a year or more, making the ongoing maintenance of existing machines a vital component of quality control and quantity of production.

“It’s not easy to keep artists and businesspeople happy all at the same time. That’s what this industry really is—a balance between those people,” Quinlan said.

New Orleans artists and labels

Many local artists print their music on vinyl and many more use NORP almost exclusively. The company prints records for Anders Osborne, Bonerama, Big Freedia, PJ Morton, and JJ Grey, to name but a few. They’ve also printed for local record labels, including Basin Street Records and Community Records.

“Shipping costs a lot,” Quinlan said. “It’s about $400 to $500 to ship 500 records.”

Beyond helping local artists skip shipping costs, NORP has a personal stake in local music. Quinlan manages groups like The New Orleans Suspects, Erica Falls and some Mardi Gras Indian bands. Co-owners Bryce White and Scott Bourne run Sinking City Records. Many employees play in bands or have other music-related side gigs.

Wyatt True assists in the pressing process at NORP by visually inspecting each record before sending the vinyl disks to the next work station.

With all those clients combined, NORP finds itself in the difficult position of appeasing everyone from major labels to New Orleans heavy hitters to even indies.

“Once you get into the majors, they’re willing to take all of your volume,” Quinlan said. “So as a responsible local business owner, you have to balance meeting that demand. Saying yes to your dream client—which is the client that has as much work as you want forever—but also being true to your roots.”

When NORP launched in 2017, there was no shortage of customers in New Orleans. One local record label, Community Records, has almost exclusively worked with NORP since its opening.

“They definitely prioritize New Orleans artists and labels,” said Daniel “D-Ray” Ray, co-owner of Community Records. “If there’s a gap in the schedule and they can make it happen, they’ll throw you ahead without sacrificing other jobs.”

NORP is shielding some artists from more lengthy wait times. According to Ray, having a resource like NORP in the city allows his label to meet deadlines and be a part of the process. Even the band Bad Operation, of which Ray is a member, filmed a music video in the NORP warehouse.

Artists on major labels have had issues with delays, but smaller independent artists are suffering more acutely. Vinyl is costly, especially when compared to the lasering of CDs, and printing vinyl takes more time. In NORP’s early days, between 2017 and 2019, it could take up to three months to print a batch of vinyl. Even at their fastest, turnaround times took 28 days. As the shortage began, the entire industry saw six-month turnaround times as the standard in 2020, carrying into 2021 and 2022.

Despite challenges, artists have adapted by planning new releases and reissues around the current vinyl shortage. Local ska-punk band Joystick! waited six months before releasing their most recent record, I Can’t Take It Anymore, allowing the digital and vinyl versions to be released simultaneously. The band is signed to Bad Time Records based in California—who prints their records with Pirate Press Records—who place their orders with a company in the Czech Republic.

Eddie Bricker is a record press operator at New Orleans Record Press. He works at Sisters in Christ Records and was a silversmith before being hired at the press. Photo by Dalton Spangler.

Even with careful planning, artists can’t control everything. Because their shipment was aboard the Ever Given, a container ship that blocked the Suez Canal in March 2021, the vinyl release was held up another month. Despite the delay, sales of I Can’t Take It Anymore went well overall. Joystick! sold out of their first pressing of around 600 records in less than five weeks and had to wait another six months for a second order to arrive in January 2022.

The pandemic has contributed to an increased demand for vinyl albums. With more people stuck at home, many turned toward music and record collecting as a safe indoor hobby. Vinyl sales spiked dramatically in 2020 and that trend continued throughout 2021. Some fear that this may be an industry bubble that will crash when the fad wears off, but others believe vinyl is here to stay.

Ray has played in bands since he was 15 and has witnessed the rise of vinyl over the years. When he first started performing in the early 2000s, most bands were selling CDs and eventually MP3s through online platforms like Napster. But in punk/indie circles, vinyl was increasingly becoming a popular merch item to encourage people to buy music rather than illegally download it.

“The profit you can make on one record is more than what you can make streaming, but you definitely want to guarantee that you can sell them because it’s a good amount of money up front,” Ray said.

Bands can make decent money with a mixture of touring and selling other merchandise items like t-shirts. They could then reinvest into recording new music or capturing their music in physical formats like vinyl and CDs.

In 2008, Ray started Community Records with longtime friend Greg Rodrigue, who interned at Asian Man Records. They printed the label’s first vinyl that year for their band Fatter Than Albert’s album The Last Minute.

“It takes a minute to break even but it’s kind of the physical form of music,” Ray said. “What else are you going to put it on?”

As with most things in music, taste is subjective. Some people prefer one format over another. John “Pat” Kauchick loves collecting anything music-related. He has collected records, posters and other novelties since the ’80s. But recently, he’s begun expanding his collection to art cards and even music NFTs to fill the wait times imposed by vinyl.

“I bought two of Lizzo’s new records and it took almost a year to the day to get it,” Kauchick said.

Kauchick says vinyl is the ultimate collectible but along the shortage he’s begun noticing issues with quality control, such as broken or warped records.

“[Artists] don’t want to keep their fans waiting six months or longer for a vinyl record,” he said. “I’ve seen artists release signed cassettes and CDs instead.”

Due to the delays on vinyl, other physical formats of music have been filling the gap. Cassette and CD purchases are on an upswing. Kauchick has bought music on the vintage mediums and he’s not alone. Some people, including Ray, enjoy cassettes for nostalgic reasons.

“My first records I got as kid were Wayne’s World and Queen on cassette,” he said. “I like the tactile experience of it. The literal opening of the case, the plastic clicking sound of it going into whatever you’re playing it on and even the snap when one side is over and you have to flip it.”

Others like Quinlan who lived through the cassette tape era as young adults or teenagers and have no interest in cassettes coming back.

“They wear down super quick—they melt,” he said. “I don’t think they have the cycle vinyl does. They’re like a niche, within a niche, within a niche.”

New Orleans retail

Euclid Records, a retailer in the Bywater, specializes primarily in vinyl records but also sells CDs and cassettes. Lefty Parker, manager of the business, owns cassettes from the ’80s. “As long as they’re stored okay they’re generally pretty okay and that’s true of CDs too,” he said.

Parker has worked at Euclid Records since its opening in 2011 and was previously employed at two other record stores in the ’90s. He views the vinyl shortage as just another first-world problem that requires adaptability.

“When you build a record store, you build a community of people who will continue to buy records so long as you meet their taste and their budget,” he said. “Ten years ago, I sold records pretty well. Now, I maybe sell a little bit more, but I still see a lot of the same people.”

According to Parker, working at a record store has become both easier and harder since the ’90s. Three decades ago he would order directly via fax to a single distributor. Now, he can order instantly via email, but he has to work with dozens of people. When a release comes along that he can’t get on vinyl, he will default to CDs for New Orleans artists and cassettes for everyone else.

Parker mentioned the Louisiana Music Factory (LMF), calling them the “Grande Dame” of New Orleans record stores.

“All the artists take their stuff there because they’ve been around the longest and deserve the respect,” Parker said.

Barry Smith, the owner of LMF, has operated the store since its opening in 1992. Vinyl has always sold at LMF, but Smith has seen a slight uptick in recent years thanks to younger buyers.

“If [young people] actually want to buy music they usually want it on vinyl, and if we only have it on CD, they’re generally not interested,” Smith said. “We still have a lot of older customers that will buy CDs over the records and when there is a new local release, we usually sell two to three times as many CDs than records.”

Freeman York handles most of the music orders at LMF. According to York, he has nearly 500 backlogged vinyl orders from 2021. Albums like Jon Batiste’s We Are and Leo Nocentelli’s Another Side have been selling out quickly leaving the store shelves empty for months before new pressings arrive. It especially hurts with upcoming music festivals like the French Quarter Festival and the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

“Something like that you need to strike while the iron is hot because people are hearing it through streaming,” York said. “They want it when it releases [digitally]. And If they come in asking for it and we don’t have it they’ll just go somewhere else.”

Not only is he struggling to get vinyl on the shelves, but he’s also struggling to keep prices low.

“We got some of David Bowie’s catalog finally in stock,” York said. “We were selling it a year and a half ago for $19.99 but now we’re having to jump to $26.99. We only do a 35- to 40-percent markup. Our profit margin is the same as when we were selling it before.”

According to Parker, Euclid Records has also raised prices for most of their records by around four to six dollars due to the increased cost from distributors.

“[Major labels] are paying more to get their records pressed and they’re pushing that down to the consumer,” Parker said. “Major labels have always been speculators. Like the Adele record that everyone paints out to be the villain, [majors] paid out priority to get those records out which is raising the price.”

Expedited pressings delay other artists from printing their records. NORP claims they don’t change the queue to prioritize one order over another. They try to work in local artists when they can. The business has helped keep the work of New Orleans artists on vinyl at an affordable rate. For that, Parker is grateful.

“It’s hard to judge what the rest of the country does or says because New Orleans has always been a music-oriented city,” he said. “There’s enough support in this city for different types of [record] stores to exist here and I’m happy to be a part of the tableau.”