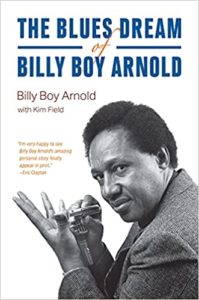

Now 86 years old, the great Billy Boy Arnold is not only the longest-tenured Chicago blues musician, but he is also one of the earliest serious blues historians. As a youth, when he wasn’t performing—Arnold is a harmonica and guitar master—he was also a devoted fan of Chicago blues. Like a home-grown detective, Arnold was documenting the genre over a decade before the British scholars began researching the blues in the early 1960s.

A Chicago native, Arnold grew up during the postwar era when urban blues began to develop. Most of the early blues musicians from this era moved to Chicago from the South, which influenced their music. Arnold had no such influences. On the harmonica, Sonny Boy Williamson I was his chief role model and Arnold collected his 78s. At age of 12, Arnold was so enthused by Williamson’s music that he tracked the bluesman down at his home in 1948. Williamson introduced Arnold to the Marine Band harmonicas, taught him how to play in “the third position” and how to “choke the harp.” Unfortunately, not long after their third meeting, his mentor was beaten to death, but it didn’t deter Arnold’s ambition.

A Chicago native, Arnold grew up during the postwar era when urban blues began to develop. Most of the early blues musicians from this era moved to Chicago from the South, which influenced their music. Arnold had no such influences. On the harmonica, Sonny Boy Williamson I was his chief role model and Arnold collected his 78s. At age of 12, Arnold was so enthused by Williamson’s music that he tracked the bluesman down at his home in 1948. Williamson introduced Arnold to the Marine Band harmonicas, taught him how to play in “the third position” and how to “choke the harp.” Unfortunately, not long after their third meeting, his mentor was beaten to death, but it didn’t deter Arnold’s ambition.

While still a minor, Arnold sought out older blues musicians by sneaking into the rough-and-tumble blues clubs. Arnold tells many fascinating tales of legendary Chicago nightclubs like the 708 Club, Sylvio’s, Pepper’s, Theresa’s and Club De Lise, as well as landmarks like Chess Records and the Maxwell Street scene. Along the way, he interacted with just about every major and minor Chicago blues artist. In 1954, Arnold details meeting guitarist Ellas McDaniel before he assumed the Bo Diddley identity. Together they fabricated “the Bo Diddley Beat,” a unique and popular rhythm. The duo auditioned for Leonard Chess which got McDaniel signed to the label. Because of a misunderstanding, Arnold would take his talent across the street to Vee Jay Records. Although not attaining the fame of his bandmate Bo Diddley, Arnold had a nice run at Vee Jay in the late 1950s, recording such classics as “I Wish You Would,” “You Got Me Wrong” and “I Was Fooled,” all which featured backing by some of the greatest Chicago musicians. Unbeknownst to Arnold, he had no idea how popular his music was and how many covers of his songs were recorded by British bands, including David Bowie and the Yardbirds, until a decade later.

In The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold, Arnold did live out his dream and became the last musician who has lived through the entire history of Chicago blues. His recollections of long-gone music venues and musicians are fascinating and unassailable. This book is simply a must-have for every blues lover.