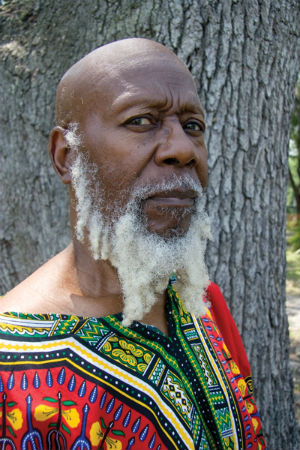

“There are some people we can’t love enough, and one is Harold Battiste.”

OffBeat contributor Jeff Hannusch used those words to begin a story about Harold Battiste, Jr.’s 2009 Best of the Beat Lifetime Achievement in Music award, and they ring just as true today as they ever have.

We had the pleasure of honoring Harold Battiste Jr. with three Best of the Beat awards.

Battiste was the recipient of our first-ever Heartbeat Award in 1996, and he earned a Lifetime Achievement in Music Education award a decade later before receiving his third honor three years later.

Hannusch rounded up some of the many musicians Battiste worked with, mentored, and helped to succeed over the years.

Here is what they had to say:

Irma Thomas

I auditioned for Harold when I was a little girl—12 or 13. He was doing A&R for Specialty Records then, but he said he couldn’t sign me because I was too young. Later, when I started making records, he played in my band for a short time, but then he moved to California. When I moved to California (late ’60s), I saw him once. He hired me to sing background on a Sonny and Cher session. He was very business-like, got right to the point, but he was a very nice man.

Mac Rebennack

I gotta say, I had some good experiences with Harold, and some bad ones. But after all is said and done, the good outweighed the bad. Back when he was with Specialty, he was the first guy that got me in the studio and into some good music. Harold was always a great judge of material. I had a problem early on, though, because I didn’t know anything about copyrights and I lost a lot of my songs to the powers that be.

When he got into the AFO thing, Harold used me on sessions on guitar when Roy Montrell wasn’t available. He really helped get me on sessions when I went out to California. We did a lot of Sonny and Cher, and Phil Spector dates together. Of course, later we worked together on the Gris Gris and Babylon albums.

Deacon John

The first time I met Harold was the day I joined the Musicians Union. Harold had an office over top of Houston’s Music, which was across the street from the Union Hall on Claiborne Avenue. I remember Papoose [Walter Nelson, Jr.] was rehearsing the guitar solo that he played on [Art Neville’s], “Cha Dooky-Doo.” Later, when he started AFO Records, he occasionally called me in for sessions when Roy Montrell, who was a member of AFO, was on the road with Fats Domino. He also called me for a Duke session on Junior Parker that he arranged. He was cool in the studio; if there was a problem, he’d just say, “You guys know what to play. Let’s just get this right.”

Harold went out to Los Angeles in the early ’60s with the AFO cats, but most of them came back not long after. Harold stayed, though, and did pretty well after hooking up with Sonny and Cher, and when the Dr. John thing happened.

I think he was the most talented arranger to come out of New Orleans. When he came back to New Orleans, he buried himself in academia. He was very well-qualified for that, being a graduate at Dillard. People didn’t realize it at the time, but at the little AFO office at Orleans and Claiborne Avenue, Harold was a pioneer. It was the first black-owned music production company in New Orleans. They were the first ones to say, “We should all have a share in this business.” He opened the door for a lot of people.

Cosimo Matassa

Two things impressed me about Harold. First, he knew what he was doing. A lot of producers just sat in the booth and let things happen in the studio. Harold always had a plan. Secondly, Harold was focused. He took care of business. Compared to Dave Bartholomew, who was a taskmaster, Harold was more laid back, but he let everybody know who was in charge. He went in the studio well-prepared and there were no surprises. He was creative, but he did stuff his artist could handle. He cut the cloth to fit the body, so to speak. I wasn’t surprised at all he did so well when he went to the West Coast. Like I said, Harold knew what he doing.

Chuck Badie

When Harold called and said what kind of label he wanted to start, I said, “Count me in.” It [AFO] was a wonderful organization and I was proud of it. We did something that at the time needed to be done. Until then, it was companies from out of town that came here and made most of the records. We got paid for playing on the sessions, but those companies made the real money.

With Harold and Red Tyler, we had two guys that had been A&R guys for other labels, so they had some experience. Roy Montrell and Melvin Lastie had played on a lot of sessions, so we had experience there. John Boudreaux, Ellis Marsalis, Tami Lynn and myself weren’t amateurs either. We were lucky, and had a hit right away with Barbara George (“I Know”), but we had some unfortunate business dealings. Eventually, we realized AFO wasn’t going to be successful in New Orleans. It just wasn’t happening here.

Mark Bingham

I’ve been working with Harold since the mid-1990s when he started doing the “Harold Battiste Presents the Next Generation” series. He’s positive and always prepared. The work is already done when he gets in the studio.

The guy has so much history behind him just with AFO and the Phil Spector stuff he did. He’s always willing to answer the questions you’ve always wanted to ask him. Like he told me once, he played two instruments on Sonny and Cher’s “I Got You Babe,” including the “duh, duh duh, da da duh” part on soprano sax and got paid scale—$114. He’s a guy I’ll always look up to that has never gotten a lot of credit.