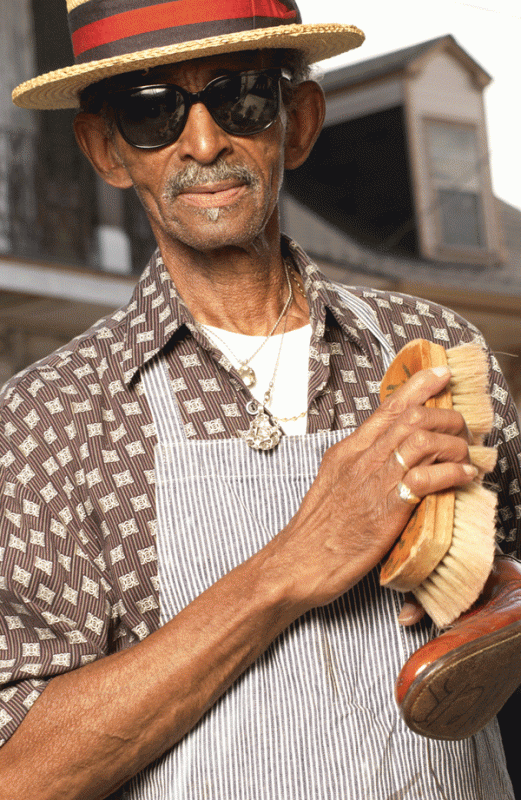

Of all the colorful char-actors who’ve populated the streets of New Orleans over the years, Uncle Lionel Batiste takes the cake. Uncle Lionel patrolled the banquette along lower Decatur and Frenchmen Streets with the panache of a potentate or prelate. Always impeccably dressed in a crisply tailored suit, usually accompanied by a color coordinated bowler hat, he sashayed down the block, a wizened figure greeting people with a smile, a nod of his head and occasionally a tip of that cap or a flourish of his walking stick. When Uncle Lionel sauntered out of his digs he was on stage – and he clearly loved to be recognized and basked in the attention he received. In addition to his ministrations toward the regular denizens of the block Unc had time for everyone and seemed to particularly enjoy the attentions of tourists, tirelessly letting them chat him up and willingly posing for endless photographs. He should have gotten a stipend from the tourist industry for his ambassador-like demeanor.

Uncle Lionel’s passing at age 81 on the morning of July 8 automatically makes Frenchmen Street a less interesting place. Other char-actors will doubtlessly try to recreate his act but no one can recreate the man. Uncle Lionel knew who he was and what he stood for. As the bass drummer for the Treme Brass Band he understood the importance of music in everyday life. He was an archetype without the desire to be a celebrity, a proud, self sufficient black man whose stage was the streets of his community and whose demeanor spoke volumes about the nature of dignity. He represented the Sixth Ward and its Treme neighborhood as a product of the country’s first black community. His iconic figure is so ubiquitous in the HBO series Treme he might as well be the show’s brand icon the way Professor Longhair defines Tipitina’s.

During his frequent sojourns Uncle Lionel moved at an inexorable pace, attuned to the rhythms of his home town. The day Batiste died drummer Doug Belote posted an anecdote on Facebook. “Uncle Lionel, why do you wear your watch across your palm instead of on your wrist?” asked Belote. “I want everyone to know,” Lionel answered, “I have time on my hands.”

Everyone has their own favorite Uncle Lionel stories to tell. Here’s mine:

I must have passed him hundreds of times on the street and always said, “hello,” if there was an opportunity, but mostly our exchange was limited to smiles and nods while a few choice words sufficed. During his forays Uncle Lionel would often hit the various clubs along Frenchmen Street, sometimes just listening, occasionally performing a little dance while the band played, and in the best circumstances taking the mic to sing a couple of tunes. Davis Rogan, another Treme denizen, always made sure Uncle Lionel came up to sing during his gigs on Frenchmen Street. Last carnival season (2012) on the night of the Krewe du Vieux parade Rogan’s band played the Spotted Cat. The place was packed and the band’s first two sets were off-the-scale great. Uncle Lionel dropped in but watched from the wings, sipping a Miller High Life. Somewhere around 2 a.m. the intensity of the revelry kicked in and Rogan began feeling the effects of carnival magic. His throat was shot but the band careened on. Uncle Lionel was standing next to me. Smiling wickedly, he turned and said “I feel my strength.”

Suddenly we were watching a new show: the Davis Rogan band with lead singer Uncle Lionel Batiste. As the lead vocalist in the Treme band he knew a lot of songs and his guest spots were always charming. But on this night he was breathing fire. The highlight was an epic version of “Tipitina,” chorus after chorus, Davis having too much fun to care about stopping while Uncle Lionel kept adding fuel to the inferno. During one chorus he shouted the line “Hey Robertaaaaaa!” so intensely it was as if he stopped the world for a moment, freezing time for the Mardi Gras magic to take over and thrust the spirit of Professor Longhair into Uncle Lionel’s body. What, only moments before, looked like a Frenchmen Street gig careening off the rails in the after midnight revelry turned into a time warp of spirit possession that encompassed the whole club.

Perhaps some Mardi Gras night-years from now someone will get up in front of some band on Frenchmen Street and start singing until the spirit of Uncle Lionel possesses them. I hope I’m there to hear it.

Thank you, Uncle Lionel!