In this month’s issue of OffBeat, we took a last look at the first season of Treme. For it, editor Alex Rawls spoke to Steve Earle and producer Eric Overmyer. OffBeat.com has already run additional material from Rawls’ talk with Earle; here is more of his interview with Overmyer.

How did you feel about the response to the show?

We were all moved and gratified at how intensely positive most of the reaction of New Orleans was. It’s what we hoped for, but we weren’t at all sure about it. I think the intensity of that struck me; I guess it surprised me how close to the surface everybody’s feelings still are about that time. I’ve never worked on a show where the response has been so intensely personal. It’s just a TV show, right? I don’t think it would be replicated anywhere else in country where it is just a TV show.

Were there responses outside of New Orleans that surprised you?

I knew going in that New Orleans is not for everyone. Some people just don’t get it or don’t like it, and that’s fine. I figured that would be true of the show, too. Some of that was confirmed for me, some of the reaction outside of New Orleans. There was a theme in some of the reviews about name dropping, which I also found very puzzling. Like we were supposed to make up musicians’ names? Not use the ones in New Orleans? That would be really odd. ‘Okay so we’ll pretend Allen Toussaint and the Neville Brothers don’t exist, and we’ll call them something else.’ What are we supposed to do here? This is about musicians.

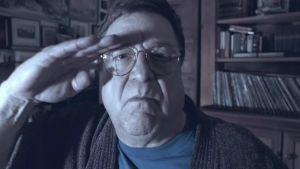

A lot of the national response was positive, but some of it I thought was obtuse, or fell in the camp of “I don’t like anything about New Orleans music”, which is fine. But then it’s like when John Goodman says to the reporter in the first episode, “Then what the fuck are you doing down here?” Why write about it then if it’s not your cup of tea, if you don’t have any interest in it?

I found it interesting that some critics didn’t like the show because they didn’t like being lectured by John Goodman’s Creighton Bernette, and they didn’t like the way Michiel Huisman’s Sonny treated the visiting relief workers in the second episode.

That’s always a sign of bad criticism, when the critic confuses the character’s point of view with the show’s point of view. And even with Sonny and the volunteers, for instance, it reflected badly on Sonny, not the children from Wisconsin. They were having a wonderful time in the episode. It was a completely kneejerk reaction, “Oh, we’re from somewhere else, so you’re making fun of us.” It was a character introduction to a guy that everybody agrees is a complete asshole.

The defensiveness about Creighton and his political point of view was interesting, too. I had several conversations with people who said, “That rhetoric is so overheated”, and I said, “It’s not rhetoric; it’s a fact. It’s how everybody in New Orleans feels, certainly, and it’s the character’s point of view.” I happen to agree with it, but it’s not about what me and Dave think; it’s the character’s point of view.

Are you inundated with suggestions from people who lived here about stories you should do?

Not so much. Everyone’s got a million stories about that time, and everyone wants to tell those stories, so we hear some of that, but more, “Oh man, I can’t believe you told that. That’s just like something that happened to me.” Not so much of the “You really ought to be doing this and that,” especially once the show got started and we got on the air.

I remember during the Treme panel on the Music Heritage Stage during Jazz Fest, many fans thought you should recreate Jazz Fest 2006.

I meant what I said then: Talk to HBO. If they had given us two more episodes, we could have done Jazz Fest. I’ve already done a lot of scratching my head, because Season Two starts in roughly the same place in November 2006, which jumps us past the re-opening of the Superdome. We just can’t do every significant event.

What time period will the next season cover?

It’ll be November 2006 through Spring 2007. That’s the window we are planning on staying with. It’s partly because that’s when we are shooting, so we don’t have to fake anything. It also seems to be the meat of the New Orleans calendar, Thanksgiving through Mardi Gras and St. Pat’s and St. Joe’s. Maybe we’ll get a ton of Jazz Fest footage, I don’t know.

I’d imagine that shooting Jazz Fest would be pretty daunting. Was it hard recreating Mardi Gras 2006?

A little bit. We had a little bit of Mardi Gras 2010 and filled it in there. We captured that during the day. We had a marching band that didn’t really fit [St. Aug’s Marching 100 appeared instead of the MAX Band, which combined St. Mary’s, St. Aug and Xavier Prep for that Mardi Gras season]. Otherwise, we staged everything else. I think we did pretty well, partly because we put out a call for people to bring their costumes from Mardi Gras 2006, and a large number of people still had them. It would be hard to do any place but New Orleans. We put an extra couple days on the schedule, so it worked well.

What are your thoughts now looking back at the first season?

I think the last three or four episodes started to really pay off for me. I mean, partly that’s because you set stuff up and eventually it starts to pay off. Seven, eight, nine, ten I think were really strong, they worked pretty much the way we wanted them to work.

There aren’t too many things I think we missed the boat on entirely. Episode four, there was certain things that Delmond did in New York—I think we didn’t do as well as we could have there. The problem with shooting New York is that there’s nowhere that hasn’t been shot before. We’re shooting New Orleans in ways that people haven’t shot it before and that’s pretty easy because no one has ever taken the trouble to do it. But New York, what hasn’t been shot in New York?

How did you feel about the way the show handled introducing people to New Orleans’ figures and culture?

How did you feel about the way the show handled introducing people to New Orleans’ figures and culture?

I was just thinking about when McAlary is taking Janette around, and he takes her Uptown to Le Bon Temps and it’s the Soul Rebels and John Mooney, but we never say who they are, you know. You either know or you don’t, and maybe if you know a little extra, you know they’ve never played together before. It’s a great number. We try to make it organic, there’s no reason for anybody to say, “Hey look, John Mooney and the Soul Rebels.”

We tried to make all that organic. We’ve got this character named Batiste, who plays with people all over town. I guess there were occasions when we were more expository than we should have been.

One that stood out for me was the Mardi Gras episode when the subdudes’ John Magnie showed up at Davis’ party and someone said something like, “Look, it’s John Magnie.” For the 10 percent of the country who know him, such an introduction wasn’t necessary, and for the 90 who don’t, the introduction was no help.

We had a lot of discussion about that one the night before. I was on the side of “let’s not,” and I thought it was too bald. I agree with you. It involved a lot of discussion. I just thought, “Why say that?” You know, “Oh shit, Magnie’s in the house.” Ouch, you know? I think there’s probably more than one instance where we got a little too conventional with the introduction.

What did you learn over the course of the season?

I was talking to Dave Walker [of The Times-Picayune] about this, oddly enough. He was asking about the pilot episode and the second line in the pilot. He was being complimentary, but we were learning on the job and it felt a little staged to us. It didn’t have the energy of a real second line. We wanted to try it again, so we did the one in episode six or seven, where there’s a shooting at the end of it, and for that one we tried to stage a real second line and shoot it. That one kind of got away from us. We shot about 10,000 feet of film with four cameras, but we weren’t organized enough to really keep track of the footage, so it was like wading through mud. And we lost control of the band. It was a cold day, so we didn’t have enough people show up. If we try it again, maybe we’ll try to get the right balance of control and chaos because I don’t feel like we’ve captured the energy of that type of event—it’s very hard to.

We also spent the whole season trying to figure out how to record the music live and shoot it live, to try to capture that energy of live performance. I feel like we learned some of that, how to shoot the show. I think we ended up feeling like, at the end, it’s really hard to shoot a show entirely on location when we’ve had almost no sets. We may have a couple sets next year, but it will still be mostly on location.

How about you personally? Did you learn anything?

I learned that if you ask any Mardi Gras Indian about any Mardi Gras Indian thing, you get a completely different tale from anybody you ask. We were constantly trying to align the various opinions about what is and what isn’t in terms of Mardi Gras Indian stuff. Maybe we’ll get a little more clarity on it next season. We had about 55 conflicting opinions; that stuff turned out to be much deeper than we realized.

Right at the end of the season, we had a complete disagreement between some of our Indians as to whether Lambreaux was a Downtown Indian or an Uptown Indian. Our fabulous costume designer, Alonzo Wilson, designed and had built all of Lambreaux’s Mardi Gras Indian costumes, both in the pilot and in the last episode, and for his tribe. So we were showing footage from the last episode to every Mardi Gras Indian that came in, and we were asking, “Okay, is that a Downtown Indian or an Uptown Indian?” We never did figure it out. I kept saying, “Well, he’s a Midtown Indian.” We still haven’t sorted that out.

What are your thoughts on the season finale?

I was surprised by the intense emotional reaction to the flashback sequence of the day of and the day before. That really struck a nerve with people, took them right back.

Also, I thought Agnieszka shot episode 10 better than she shot the pilot, understandably because she knew more. That second line was good, and that was a great moment for Khandi (LaDonna) when she turned the corner there with the music. And I thought Melissa Leo did really well with that.

Did you know from the start that Creighton was going to die?

Yeah, we didn’t know if he was going to commit suicide, but it was a strong possibility from the start. We knew we had to deal with that because it was so prevalent.

We knew we only had John for one season. We loved him so much that we kept saying, “You know, you could try and not succeed.” He just looked at me, and like, “I’ve got movies to do, man.” That was preordained.

I thought it was a very positive sign that people were so upset about it.

I did too, and I think we did really well with not tipping it too much ahead of time and having it make sense in retrospect. That was a tight rope we were trying to walk. I think we were helped a little by all of the gossip about Sonny and Annie, that whole thing about them being Zach and Addie in the Quarter. That was never ever our intention. So when it cropped up, it was like, “Oh, that’s interesting.” It was kind of a red herring; it distracted people from Creighton.

In that case particularly, people’s quickness to seize on real-life figures as models for the characters actually worked in your favor.

That whole muses thing [“Muses” being the show’s term for the people who provide at least partial starting points for many of the characters.] drove me crazy. But in a way I’m sure you’re right; it helped us with that one because Ashley [Morris] didn’t commit suicide.